Put that fag out, and head this way to the Blackest Streets Miscellany

Put that fag out, and head this way to the Blackest Streets Miscellany

24 July 2017: Canada's debt to British pauper children — conference and petition

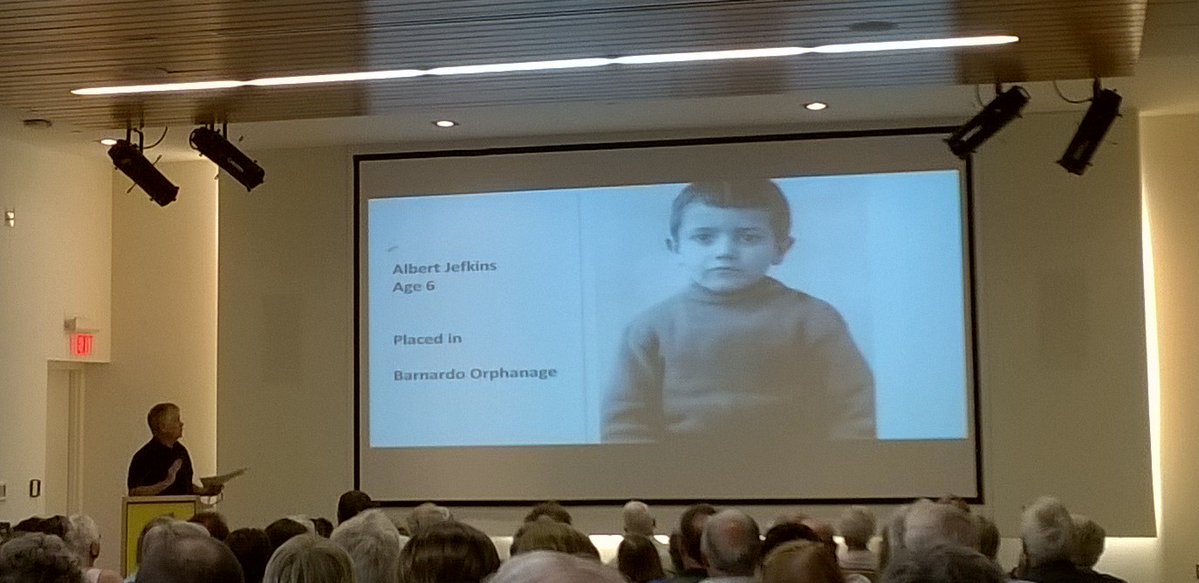

Me, left, and John Jefkins, right, talking about his father, Albert, a British Home Child emigrated to Canada

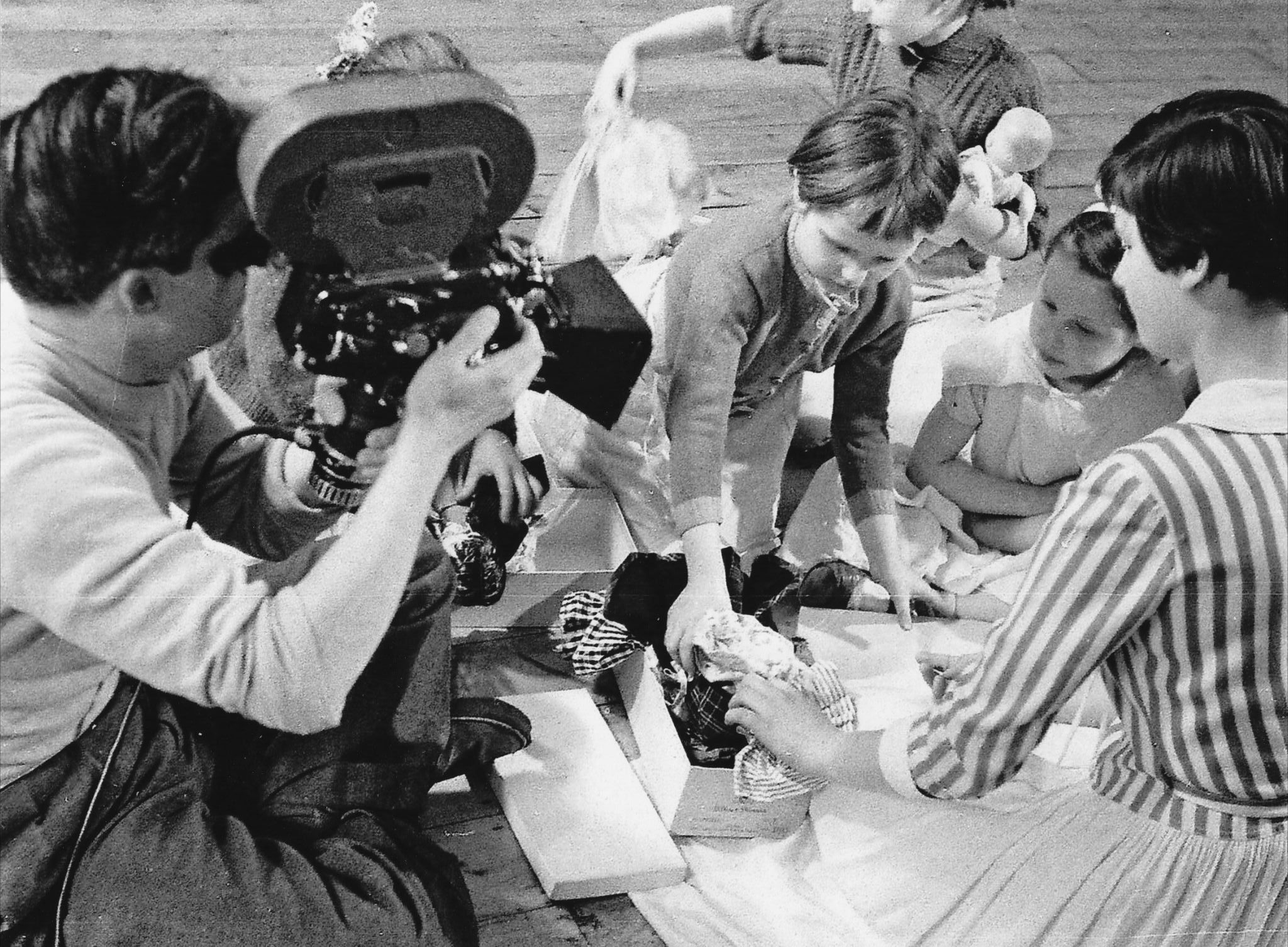

We had around 120 attendees at the British Home Child Commemoration Event at the Waterloo Regional Museum at Doon Pioneer Village, Ontario, yesterday. Lots of people who had been tracing their family trees came forward to tell me of how either a parent or a grandparent had discovered very late in their lives that they had in fact not been orphans when they were shipped out from England, but that they had had parents and siblings from whom they were forcibly separated. I heard many moving stories of how the pain of that loss carried on down the generations. Also there was often asense of shame felt by some of that older generation because the very phrase, 'British Home Child', had carried with it a stigma — of deep chronic poverty and of somehow having been exiled from Britain, the land of their birth, unwanted and unvalued in their home nation.

Many people in Britain and Canada are aware of the government enquiry and subsequent apology that was given to the British children who were shipped out to Australia and abused, exploited and neglected. While the poor treatment of many of the Canadian Home Children tended not to be on that larger, institutional scale, nevertheless, there is a growing call, spearheaded by The British Home Children Advocacy and Research Association (http://www.britishhomechildren.com/) for Canada similarly to recognise the suffering and to commit to a full inquiry and apology.

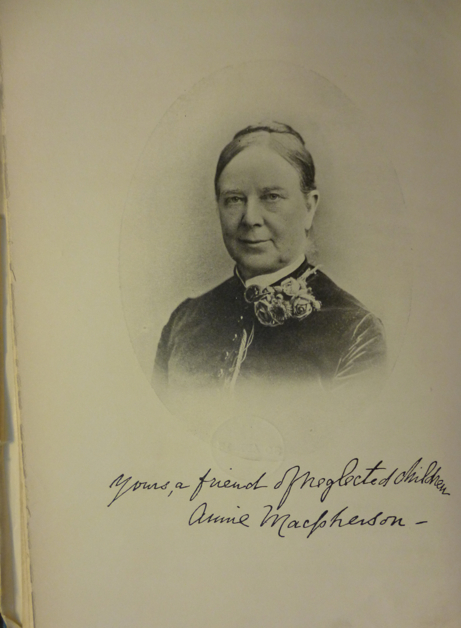

My own interest began when I was researching The Blackest Streets. Among the charity workers I came across was Annie Macpherson (pictured below), who ran refuges for street girls and boys, taught them the basics of a trade, and a basic education. I knew that she was also involved in an emigration programme that shipped some 14,000 London children out to Canada to work as farm labourers and domestic servants. But it wasn't until a reader contacted me via this website to say that he was the descendant of one such mother, a Bethnal Green widow, who had had to give up one of her 8 children as she couldn't afford to keep him, that I realised the real impact of families being broken up and children sent to Canada from London.

This correspondent of mine wished to remain anonymous, as he stated that the pain of the break-up of the family and the forcing overseas of one of its members had echoed down the generations — affecting emotionally both his grandfather and his father, and so, indirectly, himself..

In total, it is estimated that about 100,000 poor British children were sent out by various agencies to Canada between the late 1860s and the middle of the 20th century. Canadian farmers needed labour to be able to continue clearing and cultivating the land; it was massively labour intensive. Hearing that there were around 30,000 homeless street children in London; plus another 60,000 children in British workhouses, they sought to have these children sent over to help out.

The children worked unpaid till the age of 18, although their board and meals were provided. What fascinates me is the clash of ideas and of motivations. On the one hand, people such as Annie Macpherson wanted only the best for poor London children, and spent their own money on these emigration schemes; on the other, their naivety was pretty unforgiveable and even when clear cases of assault, neglect, abuse and overwork were shown to them, they preferred to believe that everything would be alright and that things would just sort themselves out.

A government inspector, Andrew Doyle, came out from London to try to follow up on some of the children. He travelled across Canada for 6 months in 1875 and found many worrying cases of neglect and abuse. Although the Canadian experience does not seem to have been so uniformly awful as that of UK children sent en masse to Australia, there nevertheless is enough evidence of hardship to warrant a large-scale hearing into the case. Most people have little awareness of these stories of what the British Home Children went through and the emotional cost.

I've written more about Annie Macpherson here: http://spitalfieldslife.com/2015/11/25/annie-macpherson-the-gutter-children/

6 minutes of me on the radio talking about the British Home Children:

http://www.cbc.ca/listen/shows/the-morning-edition-k-w/episode/13478061

Last week Gordon Brown re-involved himself in the issue of UK child emigrants to Australia. More on that here::

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/child-sex-abuse-inquiry-jimmy-savile-forced-transportation-deportation-to-australia-gordon-brown-a7852041.html

A petitition to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is here: https://www.change.org/p/open-letter-to-the-right-honourable-prime-minister-trudeau

9 December 2016: Lists of the Lost – excerpts from the Booth Notebooks in the LSE Library

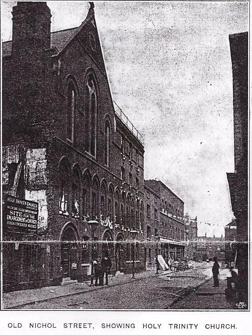

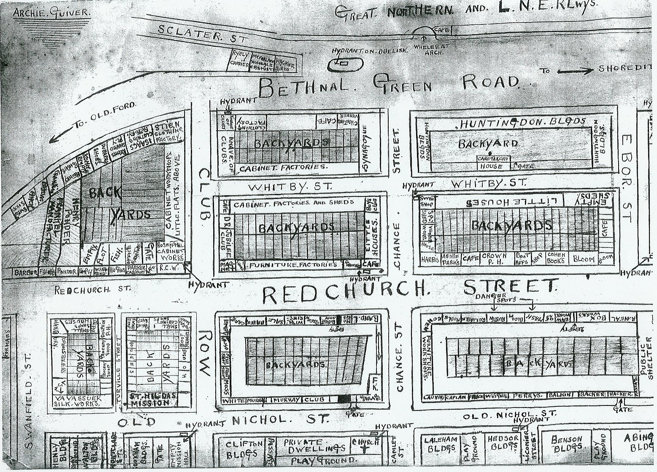

Below is a sample of the information I took from Notebooks B/77 and B/80 in the Booth Archives at the London School of Economics. The notebooks are the combined work of Reverend Arthur Osborne Jay of Holy Trinity, Old Nichol Street, and his curate, Rupert St Leger, who did the original door-knocking and questioning, using Charles Booth’s own questionnaire. The surveying was undertaken in the Old Nichol slum, East London, between February 1889 and March 1890.

There’s something relentless about lists; detail upon detail is piled up here – a catalogue of misery, made all the more powerful by the cool, disinterested nature of the inquirers. In the Nichol, many residents chose not to answer their door; others objected to being questoned about their financial circumstances and their health problems. Hence the gaps, and the lack of detail apart from names, for some of the multiple-occupancy buildings. Sometimes, the resident did invite the visitor in, for an extended interview. People were dying slowly, killed by poverty; yet no one on the Booth survey team thought to interview the landlords, leaseholders, sweat-shop workers, and the tiers of the population who made a good living from high rents and low wages.

These and all the other notebooks (46 for the East End alone) used to compile Booth’s 17-volume Life and Labour of the People in London can be found in the LSE Library. Much of the survey work can be found on the LSE’s recently relaunched Booth website http://booth.lse.ac.uk/map/13/-0.1191/51.5009/100/0

Notebook B/77

New Nicholl St [sic] May 1889

No 1

• Freeth, elderly widowed mangler of 37 yrs in the Nichol. ‘Very reserved.’

• Burks, widowed mantle maker, 2 children, earns 5 shillings a week but sometimes 3 and a half shillings. ‘Rats infest the room by daylight.’

No 2

Moleman. ‘Jews. Very friendly.’

No 3

• Clapp, widow, five children, washerwoman, and her father in his 70s, a basket weaver. ‘Very civil and poor.’

• Knight

No 4

• Bates. ‘Child came to door and said “Not today” to visitor. Grandmother lying down’... On second visit, ‘very poor indeed... upholsterer, wife and five children, two with measles, wife weakly.’

• Wykes, silk winder for Vavasseur [silk merchants], widow, very ill, 2 children in the orphanage. She is about to go into hospital.

• Seaward

No 5

• Dixon, an old established shop premises.

• Leagers, an [alcohol] abstainer, ‘wife a noisy, vulgar woman.’

No 6

• Litmann, wife and seven children. ‘Very decent.’

• Ellis

Pub — The Admiral Vernon

No 7

• Noble, a widow, in bed on the floor with rheumatic gout, does needlework when she can, one son disabled through accident, another at a sawmills, one grandchild with them, been here nine years, ‘very poor.’

• Church, a hawker

No 10

• Spall, car-man, in bed with rheumatism, wife and 8 children, only one at work, one very ill, ‘not expected to live’. Here 9 years, ‘Have been assisted medically.’

• Bordon, French-descended weavers, elderly man and wife both at work at their looms.

No 11

Jonas, watercress-seller in summer, sweep in winter, wife and 5 children.

No 12

• Hall, works in the brandy vaults, has a grown-up son at the Docks. ‘Were all having tea very comfortably by a large fire, and the visitor joined them. Well-disposed and intelligent.’

• Wells. Gout and unable to work. Wesleyan.

• Richardson

No 13

Banks, upholsterer, has whole house.

No 14

Cork

No 15 Vavasseur & Co, silk merchants

No 19

• Schenks. Landlord is Hacker.

• Hageley

No 19

Clark

No 20

• Berry

• Wyatt

No 21

• Hardy

• Bullen. Newly arrived.

No 22 is a public house, The Five Inkhorns

No 23

• A corner shop

• Vogel, German baker with an English wife.

No 25

• Hoy

• Burman, a 75yr old weaver, twice married, no family, in fair health and working at his loom. He says that Vavasseur employs 40 weavers.

No 26

• Davis and rheumatic wife, with five children. ‘Wretched home – windows broken, floor rotten, walls crumbling, eaten alive with bugs, chimney smokes fearfully. Furniture consists of two bedsteads, a table with a very ragged cloth on it and two or three other necessaries. Rent 3 shillings and ninepence. Are in arrears and pay off 3d weekly back rent. Mrs Thompson owns the house and is very strict regarding rent. Puts their goods in the back yard.’

• Jones, in first floor front. ‘Paints Christmas card sheets. Had 40 dozen to do. Takes him 2 days, from 9am to 11pm and only gets 2 shillings and 6d for them, out of which he finds his own paints, costing about 7d. Works for Taylor & Smith of Brick Lane. Widower aged 65. No children. Lives alone. Here 3 years. Rent 2 shillings and ninepence. A vile room. Ceiling quite black.’

• Corsham, a bill poster. Been here 7 years. ‘Wretched room – paper hanging from ceiling in ribbons. 2 large holes in the floor, very smoky. Rent 4 shillings – owes 3 months.’

• Barr, slippermaker, gets 4 shillings per dozen, and they sell at 4 shillings 11d a pair at least. It takes himself and his wife 16 hours to do a dozen pairs, and earns about 22 shillings a week, working 16 hrs a day. ‘Wretched room – walls and ceiling damp and mouldy and room full of dense smoke. Parts of ceiling fallen away. Very poorly furnished. Rent 3 shillings and 6d.’

No 27

• Collins

• Lillie

• Giles, a widow who makes stokers’ mitts. ‘A vile room – cannot have a fire on account of smoke from chimney.’

• Stearbridge

No 28

• Taylor

• Graystock. Flower-stand maker. Total abstainer. Wife drinks.

No 29

Skinner, wood chopper; wife recently delivered of a baby and very weak, works at fancy-box-making when able. ‘Wretched home – 1 bottomless chair and a bed almost the only furniture.’

No 31

Cleeve, brushmaker, 7 children, rheumatic, works for [John] Grimwood [of nearby Church St].

No 32

• Barnes, man and wife, ‘friendly.’

• Ball

• Top floor ‘occupied by a large family, 2 men, and six women and girls. Saw two young men and some girls. One of them said his name was Stevens, and that he would be at Father Jay’s club on the Wednesday. Is said to be a fighting man. Girls are flower girls. Rooms filthily dirty and other lodgers complain of their dirty and noisy habits.’

• Lampey

Nos 34 and 35

Sisters of the Church, and Mrs Hutton, their housekeeper. [The Kilburn Sisters’ Orphanage of Mercy Mission Rooms/soup kitchen.]

No 36

• Wall, blind, deaf, neuralgic widow, run over 4 years ago; and her family. Some are in the workhouse.

• Akens

• Dudley

No 37

• Howes

• Warley, widow, belongs to the Phoenix Order [masonic lodge]. ‘Complained of the danger of Old Nichol Street and mentioned recent cases of robbery there.’

No 38

• Deakins, wife and child. ‘Very dirty room, child no boots. Expects property ... by deed of gift, he having befriended one of the partners in the Chancery suit now pending. Is to have a block of buildings if his friend succeeds in the suit. Wife showed visitor a lot of documents and a deed of gift on parchment. Man has done 17 days in Holloway Gaol for contempt of court, and has been waylaid and kicked and stabbed (according to wife) by the emissaries of the opposite party for the part he has taken in the case. Wife says the [Church of England] Sisters’ store is abused by people who beg the clothes and then sell them.’

• Warner

No 39

• Mears

• Cook, a shop

No 40

• Robinson, widow, ‘room indescribably filthy and miserable. Very dirty old woman hobbled forward and expressed her strong objection to visitors.’

• Hastings, a blacksmith.

• Archer, railway porter, ‘decent and intelligent but said to drink.’

No 41

Abbott

No 42

• White

• Woodcock

• Williams

• Hewitt

No 43

Harding, a hawker, sells oleographs in the street, trade ‘very slack...Very rough, dirty room, gets help from a mission room near by.’

Notebook B/80

Half Nicholl St [sic]

No 2

• Greengrocers

• Humphreys, ‘an old soldier. Wife Roman Catholic, has bad face, blood poisoning, decent people, get on, not good to wife.’

• Carver

• Harwood

• Pomeroy, street seller, and family.

No 4

• Jackson, ‘decent and industrious.’

• Gavigan, wife of a former optician who is now in Hanwell Lunatic Asylum as he had ‘a tendency to suicide.’

• Mrs Ashton

• Hersey, who says ‘people used to be allowed to take 3 rooms and sublet, but this was altered because the chief tenants, while exacting the rents from the subtenants, did not pay the landlord. Hersey seems a nice respectable old man.’

No 6

The Callans, ‘a bad lot... Very rough and rude. Drink heavily.’

No 7

* Knight, fancy-box-maker, ‘busy at work and very unfriendly. Woman here the same. Seems to have given visitor a bit of her mind, and spoke of his [Father Jay’s] club as a place that she should not like her husband to go, on account of the “sparring” [boxing].’

No 18

Strahan’s [lettings agent] office. He says it’s hard to get the rent out of them, and they have no goods worth seizing. ‘Very nice little man. Had a large loom in his room. Lives in King Edwards Road [Hackney].’

No 20

• Coquard, weaver for Vavasseur, over 80, lived there since 1849, the year of the cholera, and recalls the ‘horror of that time, when every house in the street had its shutter up.’ Huguenot descent. Breathing hard. Born in Bethnal Green, brought up in Spitalfields. He remembers the long weavers’ rooms being divided up to make more rooms to let. His second wife died 5 years ago, ‘she had deserted him. Neighbours say his first wife hung herself in the room in which he still lives.’

• Sestar, an engineer, he and his son, a boxer, both belong to Father Jay’s club.

No 24

• Parsons, a hatter, whose wife, 67, has been laid up for three years with rheumatic gout, ‘a very talkative, cheerful woman although suffering with great pain. Says [Reverend] Spurgeon has same symptoms as herself, and so had Lord Palmerston... The house belongs to Mrs Lock (widow) who lives in the court. Rents collected by an agent.’

No 26

• Watts, a shellfish-stall-holder in Shoreditch, also a chestnut stand. Wife bed-ridden by bronchitis and heavily pregnant. ‘Wife’s first husband used to stand in front of Shoreditch Church and open carriage doors for wedding parties. Well-known character. Wife’s great grievance seemed to be the way in which her last child was buried by a local undertaker. Charged her 30 shillings; owed him 8 shillings of it and was not inclined to pay it because of inferior style. People made remarks.’

No 28

• Howson, an elderly cabinet maker and cousin of the late Dean Howson. From Appleby in Westmoreland and came to London aged 25 after tramping 300 miles through Britain in search of employment, for 36 weeks, once walked 60 miles in 12 hours. Is an Oddfellow, and was also a Forester, and got travelling pay from both orders. He presents their card to local officer at each place and gets a 1d a mile allowance. Is now a convert and regular churchgoer. Wife rheumatic, also religious.’

No 32

Courtney, a Frenchman, objects to [Father] Jay’s club on account of ‘sparring – says many others do so too.’

No 38

Usher, blacksmith, ‘man and wife both drunkards. Room in a most filthy condition – stink dreadful... sheets black. Man in bed when visitor called, recovering from effects of drink. 2 dirty little children playing about.’

7/12/2016 A contents page I devised for Charles Booth's Life and Labour of the People in London

I put this together for some of my students, to help them to navigate their way round the daunting-looking 17 volumes of Charles Booth's Life and Labour survey. It's a labyrinthine series of tomes, but once cracked, this is the most informative data on London at the end of the 19th century that you'll ever find.

28/11/2016 My review in The Lancet of the 'Feeding the 400' exhibition at the Foundling Museum

17/10/2016 Britney — the Bethnal Green years. Guest post by Alan Homes

Alan, who lives in Canvey Island, Essex, and who has several ancestors who lived in the Old Nichol, got in touch with me to point out that Britney Spears is another ‘child of the Jago’ — someone whose forebears can be found in the East London slum. Below, he reveals the results of his researches.

‘As anyone interested in pop music will know, Britney Spears is one of the best-selling artistes of all time, having sold 100 million albums and 100 million singles worldwide. It is reported that Spears’ earnings between 1998 and 2016 are a staggering US$670 million.

‘What has this to do with the Old Nichol? Well, Britney Spears’ great-great-grandfather, James Lewis, was born at 8 Old Nichol Street, Bethnal Green, on 22 September 1872 to an impoverished family of former weavers.

‘Britney Jean Spears was born 2 December 1981 in McComb, Mississippi, the second child of James Parnell Spears (born 1952) and Lynne Irene, nee Bridges (born 1956). Her British connection to the Old Nichol comes via her maternal line. Her maternal grandparents were Barney O’Field Bridges (1919-1978) and Lilian Irene Bridges, nee Portell (1924-1993). Barney Bridges was presumably a US serviceman in the Second World War as he married Lilian Portell at Hendon, north London, on 16 March 1945. Lilian’s surname (Portell) is a corruption of her Maltese grandfather’s surname, Portelli.

‘Lilian Portell was born in Tottenham, north London, the daughter of George Anthony Portelli (1898-1953) and Lilian Esther Portelli, nee Lewis (1897-1980), who had married at Tottenham on 29 July 1923 — Lilian was Britney’s great-grandmother. She was born at 10 Wellington Row, Bethnal Green, on 14 December 1897; and Lilian’s father, James Lewis, who worked as a barman, came from the Old Nichol.

‘James Lewis (b.1872) was the son of another James Lewis (b.1849) and Sarah, nee Isaacs (born c1850). Their marriage entry shows that James Lewis worked as a fishmonger, and gives his address 9 Old Nichol Street. He further stated that he was the son of Joseph Lewis, weaver.

‘Sarah Isaacs lived at 12 Nichol Street, her father (James Isaacs) was also a fishmonger. James signed the marriage register with a strong hand, proving he was literate; Sarah, however, merely made her mark.

‘James Lewis was born at 17 Half Nichol Street on 19 January 1849. His parents were Joseph Lewis and Mary (nee Burn). Joseph worked as a weaver, who was also literate, though Mary was not. The 1851 census finds the Lewis family (recorded as Lewes) residing at 17 Half Nichol Street, where 36-year-old Joseph was described as a "Silk Weaver HL" (handloom). Mary was 35, and their children were listed as Mary (age 12, born Spitalfields), Emma (age 10, born Bethnal Green) and James (age 2, born Bethnal Green) (HO107 / 1539 / folio 65 / page 23).

‘They had at least one other child — Edwin Lewis, born 12 July 1852 and christened at St Philip’s, Mount Street (today’s Swanfield Street) on 8 August 1852. The family address at the time was again 17 Half Nichol Street, with the father’s occupation stated as "weaver".

‘Joseph Lewis died some time between 1851 and 1861. The family were still living in the Nichol at the time of the 1861 census, with widow Mary Lewis (now employed as a basket maker) and her children James and Mary now residing at 9 Old Nichol Street (RG9 / 250 / folio 4 / page 7).

‘So, there you have it. People on a subsistence wage in Bethnal Green during the 1870s, with their great, great, granddaughter earning an astronomical U$670 million a mere 140 years later. Just shows what a bit of hard work (and a mighty lot of luck) can do for you!’

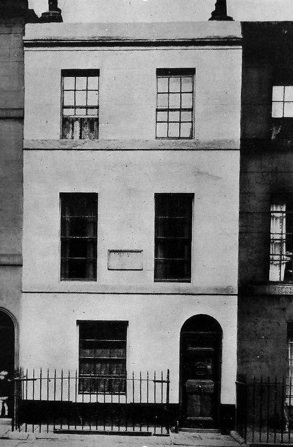

Old Nichol Street, above right, photographed circa 1888. Britney's ancestors lived at numbers

8, 9 and 12

and also in Half Nichol Street, between the 1850s and the 1880s.

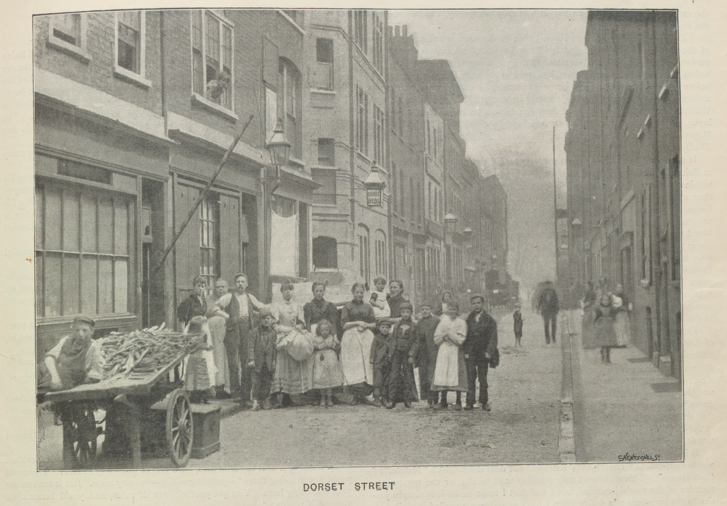

27/5/16 Previously unpublished picture of Dorset Street, Whitechapel, 1895

I accidentally caused a bit of a stir among certain sections of the Victorian East End local history scene when I tweeted a low-res version of the photo below. I’ve now obtained a better-quality scan of this 1895 shot of Dorset Street, Whitechapel, taken by a not-well-known photographer, William H Groves, for an even-less-well-known periodical — the short-lived New Budget, a general interest magazine that featured photographs and reports from all over Great Britain. East End historian Paul Begg alerted me to the photograph’s rarity and apparent significance, which prompted me to obtain this better version. (Though it has to be said, the original paper of the magazine hasn’t aged well, so this image isn’t of triffic quality, either.)

Massive thanks to the US Library of Congress, who supplied me with this scan.

Groves also shot this pub, which may (or may not) be the one that stood on the corner of Dorset Street and Crispin Street, which was called (with no trace of irony) The Horn of Plenty.

US Library of Congress

26/1/16 Getting lost in ever-changing London

One of Karl Marx’s close associates, William Liebknecht (1826-1900), was absent from London between 1862 and 1878 (he had returned to his native Germany). On his return, he was astonished at the amount of change to the physical fabric of the capital that had taken place in his 16 years away. Whole streets, buildings and even districts had disappeared as much of the Georgian city was demolished to make new for a metropolis that better expressed mercantile greatness and imperial power.

He wrote: ‘Was this the city in which I have lived for nearly half a generation and of which I then knew every street, every corner?...What revolutionary changes in the great modern cities. It is a continual uprooting... And a man starting today from a modern great city on a tour of the world will not be able to find his way through a great many quarters. Streets gone, sections disappeared – new streets, new buildings, and the general aspect so changed that in a place where I formerly could have made my way blindfolded, I had to take refuge in a cab in order to get to my near goal.’

Quoted in Marx in London by Asa Briggs and John Callow (2008).

17/4/15 A Poem of Urban Pollution, 1850

This ditty about the deteriorating atmosphere in London appeared in Household Words, 25 May 1850 – the magazine edited by Charles Dickens. It’s not by him, but it does match his fury at the failure of the authorities to clean up the fatal conditions in London. Note that it was written after the closure of the central London graveyards to new burials, but ‘miasmatic’ nastiness had not abated by 1850.

Spring-Time in the Court

‘I used to throw my casement wide

To breathe the morning’s breath;

But now I keep the window close,

The air smells so like death!...

Why are we housed like filthy swine?

Swine! They have better care,

For we are pent up with the plague,

Shut out from light and air’

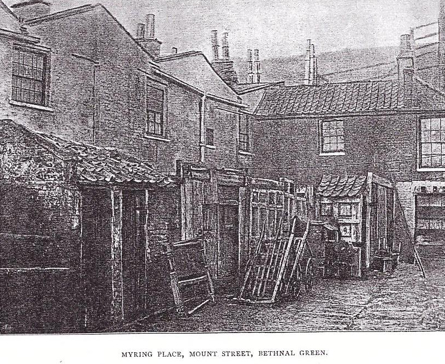

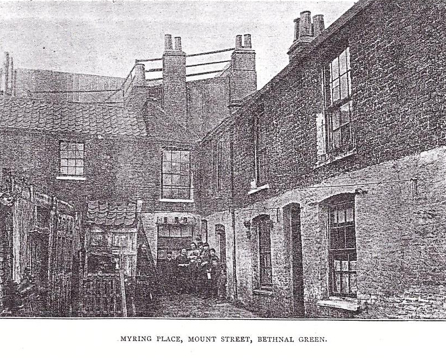

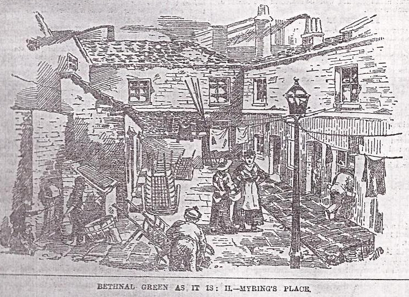

17/12/14 Myring Place, Bethnal Green — 2 photos and a drawing

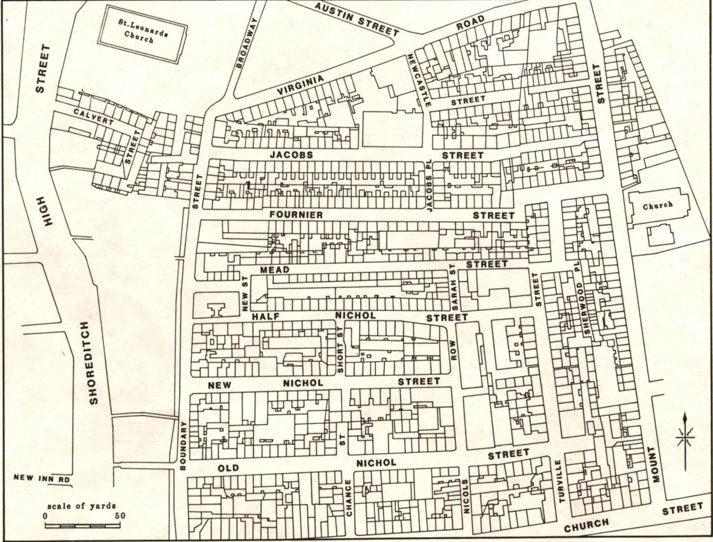

This tiny court of nine houses was known variously (even in official documents and maps) as Myring or Myrings or Mirings Place. It stood on the north-east edge of the Old Nichol slum, approximately where the small 1970s houses are today at the top end, eastern side of Swanfield Street.

The London County Council described it as ‘old, decayed and with no back-light or through-ventilation’. Sunlight and fresh air were the prerequisites of healthy living, the wisdom went; and so Myring Place’s days were numbered.

Residents of the court in the early 1890s included Alfred Cook, a labourer; blind James Schofield; Thomas Wilkins, described as a housebreaker; John Sage, a hawker; George Cook, ditto; George Barracks, no trade given; Thomas Lampey, carpenter; James Edwards, a shovel maker; and an elderly couple called Castle, who were living on charitable assistance.

The photographs below were taken for the Mansion House Council on the Dwellings of the Poor, a campaigning body, and were published in their Report for the Year Ending 31 December 1890; they seem to have been taken on a rainy and foggy day. Note the huddle of youngsters in the corner; and the upturned costermonger barrows. The illustration was in the Daily Graphic newspaper, edition dated 3 November 1890.

The London County Council bought up and demolished the toxic court, and built Streatley Buildings (now themselves demolished) on their site. (A pic of Streatley can be found below, at blog post dated 30/4/13.)

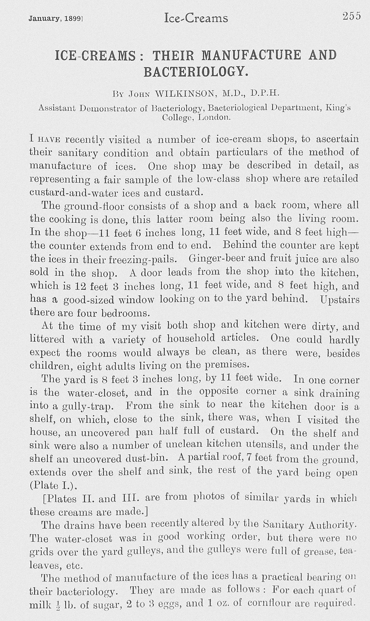

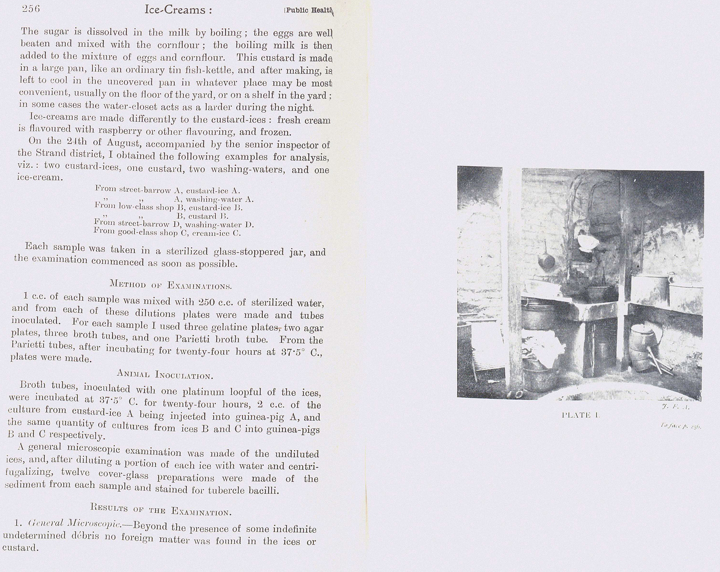

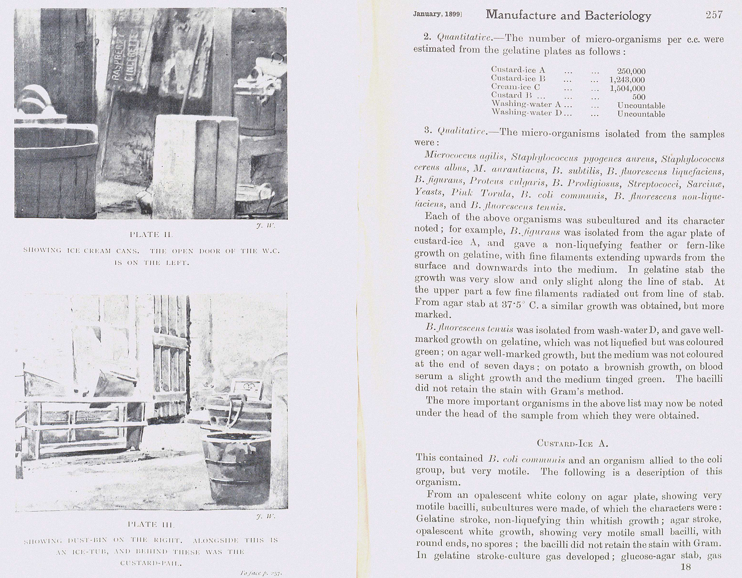

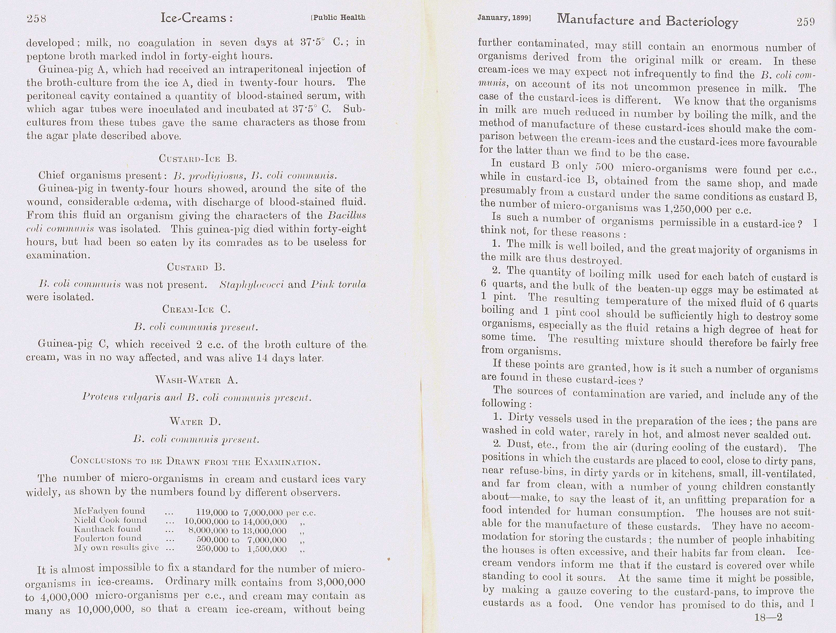

26/11/14 Ice-Cream — Again. . .

A few posts below (at 6/7/14) insanitary goings-on at a Clerkenwell ice-cream depot were revealed. Now here’s a broader, pan-London follow-up investigation, as published in Public Health magazine. Grossly unfair on guinea pigs.

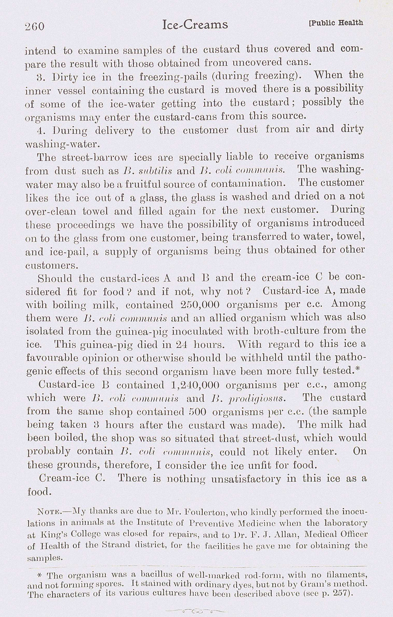

11/11/14 As hard as Charity: the ‘Geologists’ of Bethnal Green, 1887

At a meeting of the Bethnal Green Board of Guardians of the Poor (ie the local welfare office), two vicars objected to the harshness of the regime that required unemployed men to break rocks in the parish stoneyard in return for financial assistance.

This report of the Guardians’ meeting appeared in the 5 February 1887 edition of The Eastern Argus & Borough of Hackney Times newspaper, and was entitled, The ‘Geologists’ – a wry name for the poor fellers at the blunt end of the Poor Law at a time of rocketing unemployment:

‘THE “GEOLOGISTS”

‘The Reverend Mr Finch protested against the cruel employment of men for breaking granite. It was, he said, unproductive labour, and he did not care about accepting the tender for granite now before the Board. Such work was inhuman and brutal. Many of the men accepted it because they had long been out of work and were not half-fed. The Board ought to find some other kind of labour.

‘The Reverend Mr Cox said some of these poor men had to do the work without having any dinner, having nothing but a pipe of tobacco to stay their hunger. To expect such men to break hard granite was inhuman.

‘It was resolved, however, to accept the tender of Mr Fenning for 250 tons of best blue Guernsey granite at 8 shilling 3 pence per ton.’

With thanks to Stefan Dickers, Archivist, Bishopsgate Institute Library, for the image of the Bethnal Green labour yard, above.

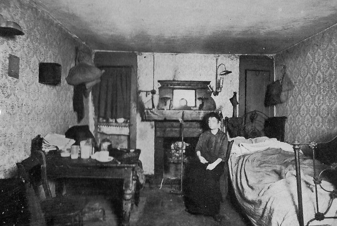

16/10/14 The blackest streets of Somers Town, in the 1920s

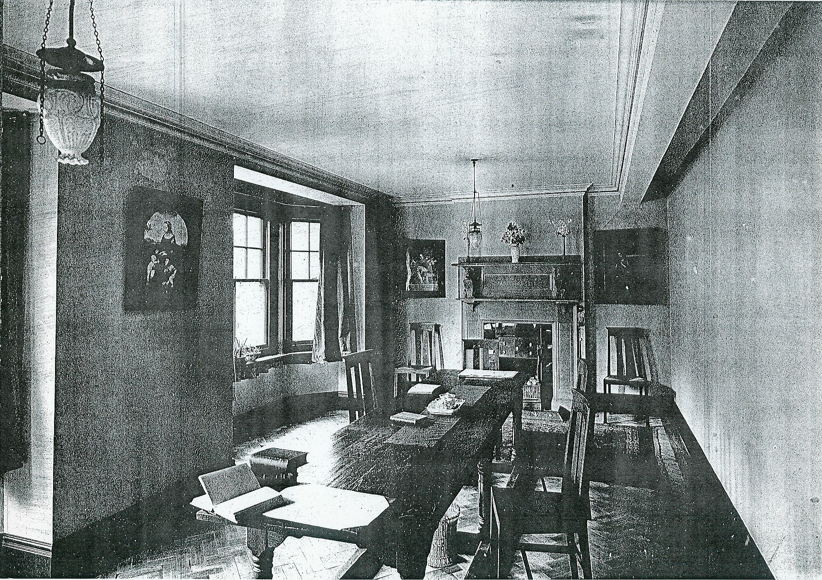

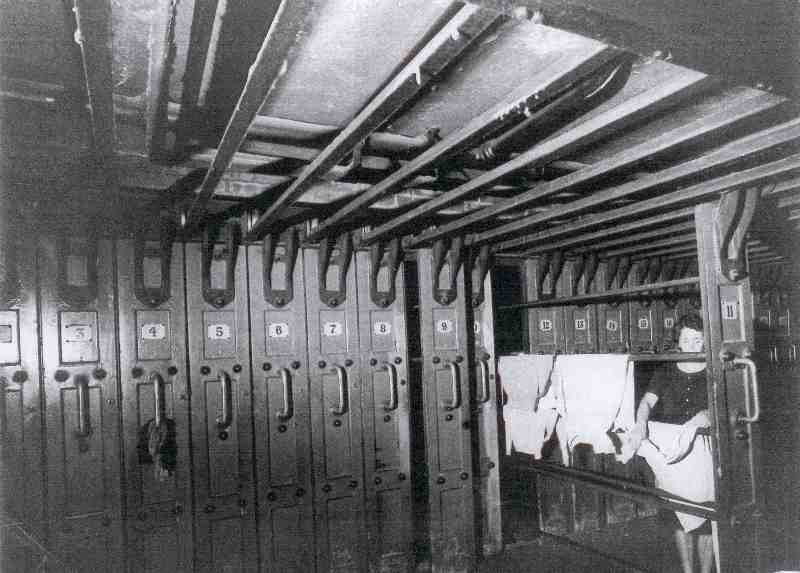

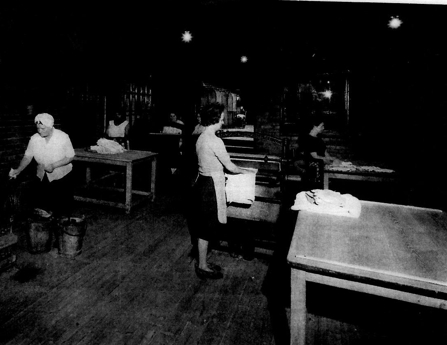

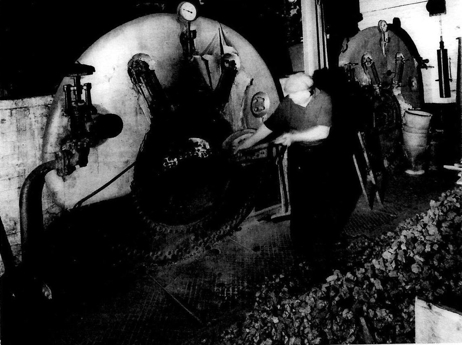

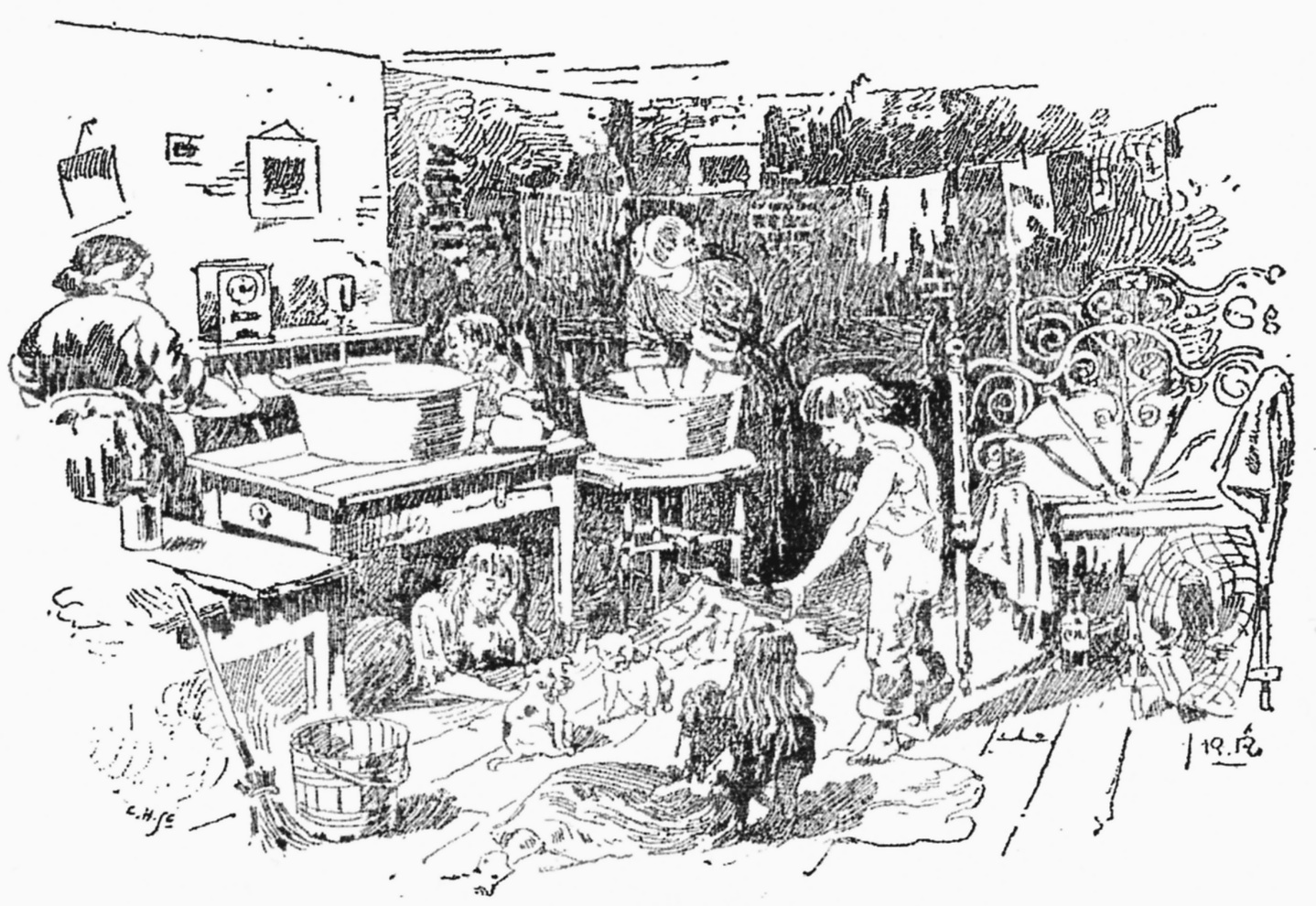

These pictures are from the book Ten Years in a London Slum: Being the Adventures of a Clerical Micawber by High Church Anglican priest Desmond Morse-Boycott. Boycott joined a brotherhood attached to St Mary the Virgin, Seymour Street (today’s Eversholt Street), Somers Town, just east of Euston station, in the 1920s, before much of the neighbourhood was demolished by the London County Council for social housing. This was to be one of the LCC’s grand successors to the Boundary Estate (see various stories below).

Below: the priests laid on charity meals for local children, a crèche, and a small basement school/workshop. In the mother-and-toddler photo are Father Basil Jellicoe, on the left, and Father Percy Maryon-Wilson on the right. For further information on their slum work, see

http://www.londonremembers.com/subjects/father-basil-jellicoe

http://www.camdennewjournal.co.uk/archive/f091003_2.htm

This Flikr site, meanwhile, has some wonderful pics of Percy Maryon-Wilson and other Anglo Catholic priests https://www.flickr.com/photos/61357634@N06/5585674049/in/photostream/

And finally, below left, I hope

I’m right in identifying The Polygon, the very unusually shaped late-Georgian housing development (where Harold Skimpole lived, in Bleak House); plus, on the right, the house in Johnson Street where Mr Micawber lived in David Copperfield.

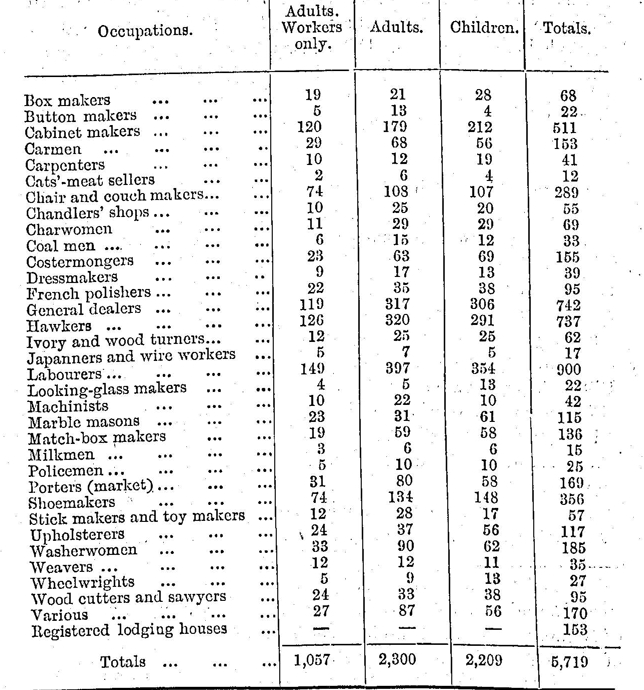

24/8/14 Come, tell me how you live (2): the occupations of the Old Nichol's residents

The London County Council surveyed the people of the Old Nichol in 1890, just as the Council was coming to a decision to demolish the slum in its entirety. The occupations given are those of the head of the household; the Nichol had a higher-than-average number of female-headed homes, which is why char-ring and dressmaking, for example, feature among the trades.

The second column numbers the adults connected with the main breadwinner (spouses, elderly parents, in-laws and so on), who may well have been in employment too (or were earning pin money), but who were to some extent dependent on the person with the named occupation; ditto the children, in column 3, many (perhaps most) of whom will have had jobs.

Many of the workers were artisans, manufacturing high-quality textiles and furniture in their homes, which had to double as workshops. These kinds of specialist trades (japanning, upholstery, marble masonry etc) were facing pressure from mass-market, ‘slop’ manufacturers, and de-skilling was taking place, with consequent downward pressure on wages.

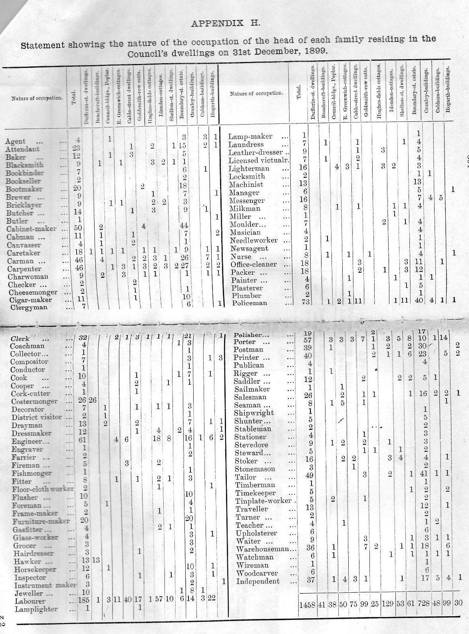

20/8/14 Come, tell me how you live (1): the occupations of London's first council tenants

The LCC surveyed its social housing tenants in 1899, 10 years after the Council came into being. This is the table that shows who was living in its first blocks and estates.

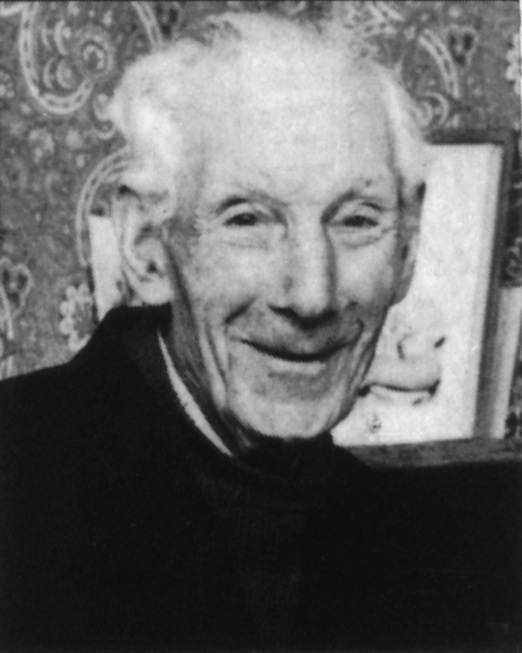

30/7/14 The vicar in the attic

So we said below (12/1/14) that no picture of Reverend Robert Whatwood Loveridge had ever been found. And then Richard Read goes and finds one among his late parents’ belongings. Richard emailed: ‘The photo was used as backing behind two certificates (for swimming and issued by the London North Western Railway Co) framed by my late father in the 1930s. Whilst my father died nearly 14 years ago the framed certificates remained in the family home’s loft until it was cleared four years ago following my mother’s death. It is only now that I have had time to look more closely at some of the items removed.’

Richard Read is not related to Reverend Loveridge but his parents were brought up in Bethnal Green in the early 20th century, as he explains in his blog post ‘Picture Perfect’ here http://thereadrovers.wordpress.com/

The reverend’s descendant, Peter Must, was delighted to be told this, and Richard Read has been a real gent and handed over the photograph to the Musts without even waiting to be asked. They are beyond thrilled.

Kevin Scully (‘Rev Kev’), present incumbent of St Matthew’s Bethnal Green, very kindly put Richard in touch with me. Thanks Rev. http://www.kevin-scully.com/about.html

6/7/14 Do you want sprinkles with that?

In 1895, at the prompting of the Medical Officer of Health for Islington, one Dr Klein made a bacterioscopic investigation of ice creams sold from barrows. Dr Klein visited one site of manufacture, in the Italian community on and around Saffron Hill, Clerkenwell. Microscopic examination of melted ice cream samples there showed traces of human excrement, a bacillus believed to exist only in the human gut, human skin cells, snot, lice and their eggs, and human hair.

In his report, Dr Klein blamed the ‘beastly habits’ of the vendors and the filthy conditions of manufacture. He voiced his fury that there was in law no requirement either to register or to inspect premises where food was prepared. He repeated his many previous calls for parliament to extend the London County Council’s powers to cover this.

Source: ‘Report on the Sanitary Condition and Vital Statistics of the Parish of St Matthew, Bethnal Green, During the Year 1895’ by George Paddock Bate.

12/6/14 Old Nichol truancy again – the tale of James Monday

Violence (on both sides), the beating of children and the calling in of the police featured in some of the tussles between the London School Board and a number of parents, who resented yet more authoritarian intrusion into their lives. Mr Tomlinson, the head of the boys’ department at the Nichol Street School,

wrote in his 1879 logbook: ‘A little boy, James Monday, eight years old, was brought into the

school yard crying but refusing to go into the ranks, had to be

carried into the classroom. He then screamed, kicked and so tried to

run out that his master sent for me, but nothing would make him move

but the cane. He got four or five strokes on his back, but continuing

to scream, I removed him to my private room, when his mother rushed in

and cursed and swore and threatened to a fearful degree. With much

difficulty I got her out of the school, but a mob assembled in the

yard and street, which was only dispersed by the arrival of the

police.

‘This is the first annoyance of the kind which has occurred in the new buildings. Such interruptions were common enough in the old school three years ago; let us hope they are fast dying

out.’

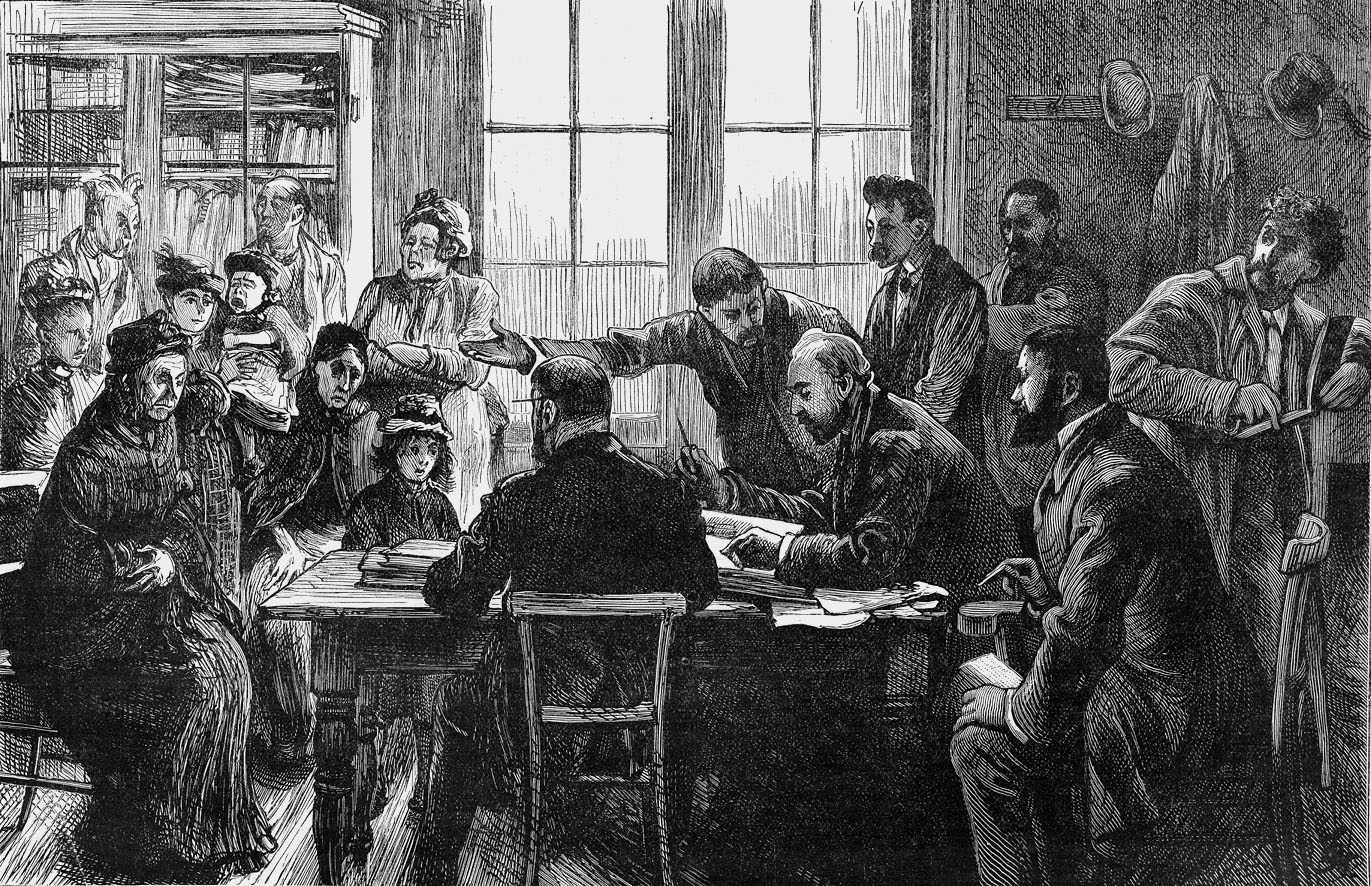

Below is an illustration of a ‘B’ Meeting in progress in East London in the 1880s. At a ‘B’ meeting, parents of persistent non-attenders were summonsed to explain themselves. The next disciplinary step up was a summons to the magistrates’ court and the threat of a fine. On the plus side, a number of London magistrates disliked the London School Board and would routinely dismiss the case against a working person, or, in the case of Montagu Williams JP, pay the find himself. This, in turn, led the Board to complain that magistrates were complicit in undermining the very thing (universal low-cost, or even free, education) that would help the poor to earn their way out of poverty.

Further reading:

Recollections of a School Attendance Officer by John Reeves (circa 1913); this very rare book is held at the Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives, 277 Bancroft Road, E1 4DQ, tel: 020 7364 1290. localhistory@towerhamlets.gov.uk

School Attendance in London 1870-1904: A Social History by David Rubinstein, Hull, 1969, is a brilliant overview of the early years of the London School Board.

The story of James Monday is found in the Nichol Street schools’ surviving paperwork at the London Metropolitan Archives, with the shelfmarks (for the boys dept) at LCC/EO/DIV05/ROC/AD/001 to 007. LMA, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1, tel: 020 7332 3820

www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visiting-the-city/archives-and-city-history/london-metropolitan-archives/visitor-information/Pages/default.aspx

8/6/14 The Old Nichol schools – coping with truancy and child ill-health in the 1880s

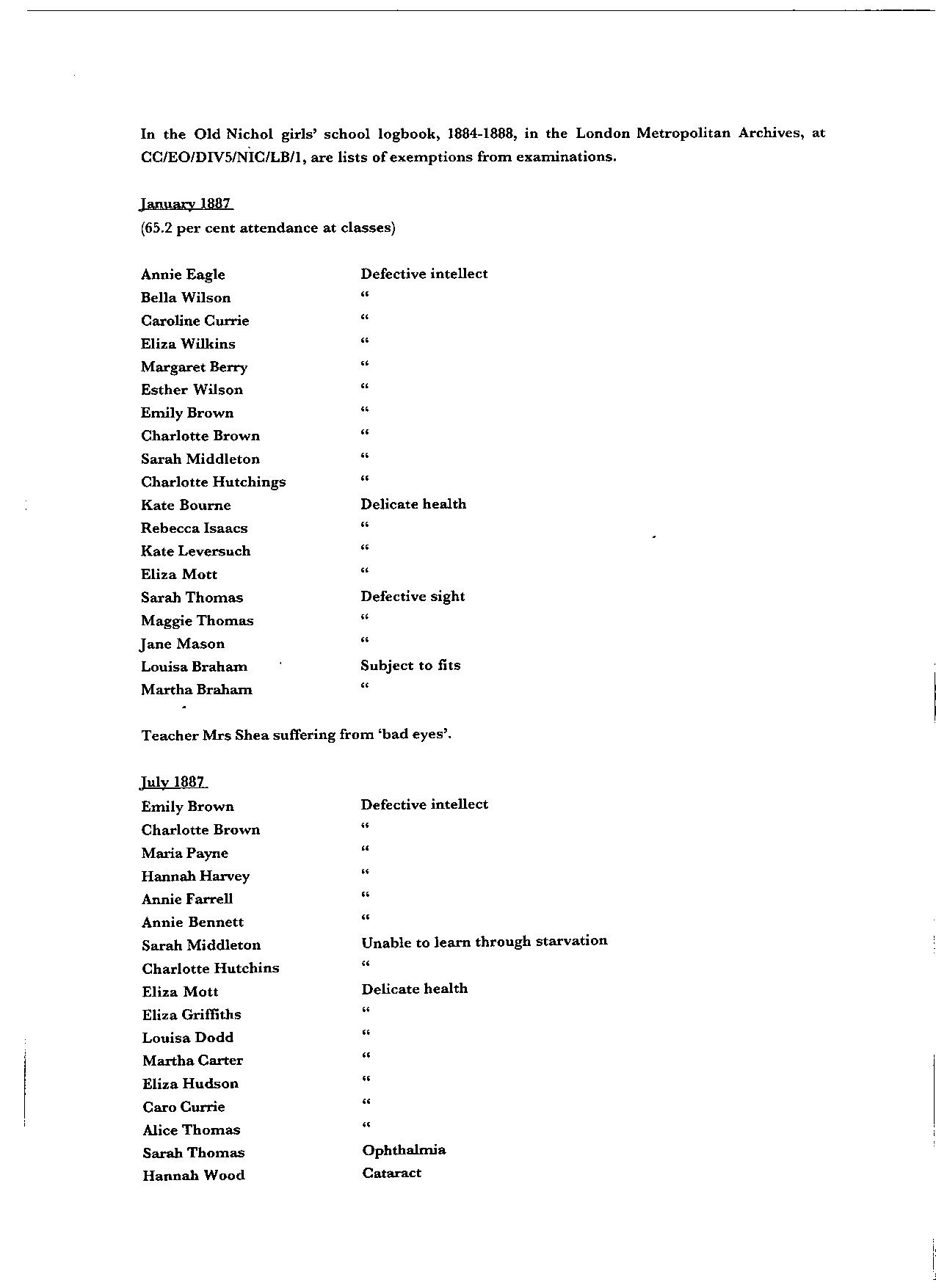

Two of the things that the schoolteachers in the Old Nichol slum were up against were persistent truancy, and the appalling state of health and sometimes semi-starvation among their pupils. With the former, children were sometimes crucial to very-poor families’ budgets, and could not easily be spared from the working day. Fighting truancy and absenteeism was a very long battle in the first 30 years of compulsory London education.

With the second, some devastatingly upsetting data from the Old Nichol schools can be found at the London Metropolitan Archives. Here are a couple of examples of the tables that one of the girls’ teachers submitted to the London School Board.

‘Defective intellect’ may well have indicated learning difficulties, or, as some teachers claimed, an inability to concentrate because of malnutrition or exhaustion. The teachers themselves went down with wave after wave of the infectious illnesses that swept through the districts (whooping cough, smallpox, scarlet fever, measles, diptheria). In the table above, Mrs Shea is likely to have been hit by the ophthalmia that affected hundreds of London schoolchildren in the 1880s and 1890s.

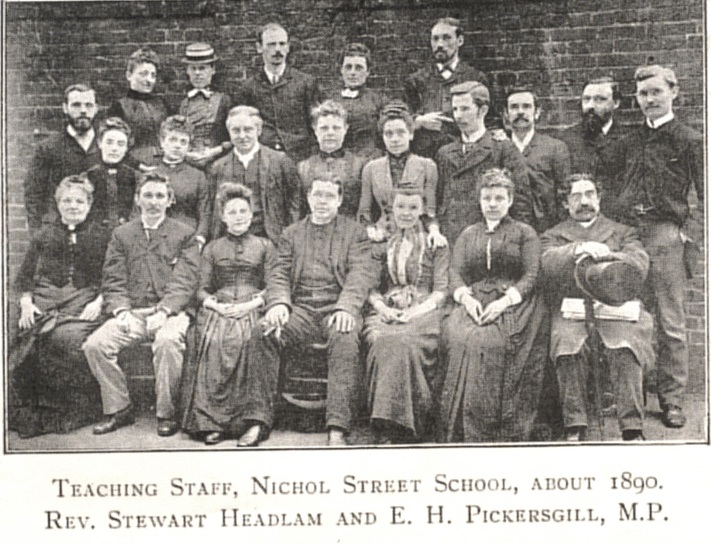

Below is a group shot of

the teachers at the schools, with local celebrity vicar Headlam (a friend and supporter of Oscar Wilde) sitting in the front row, centre, and the local (Liberal-Radical) MP Edward Pickersgill, front row, far right.

The school buildings are the only structures that survive today following the total demolition of the Old Nichol by the London County Council in the early/mid-1890s.

17/4/14 The battle for London government – what a joke

The creation of the London County Council in 1889 decided the ultimate fate of the Old Nichol slum (and what a fate). But the Council was a long time in the making: satirical magazines such as Moonshine (below right) and (more famously) Punch magazine (below left) had lots of fun in the mid- and late-1880s as Sir William Harcourt MP attempted and failed to get legislation passed to reform London’s local government by creating a unitary authority. The capital was run by some 250 separate organisations, while the medieval Corporation of London administered the City of London’s Square Mile.

Harcourt told parliament in 1884 that he knew he was ‘launching the vessel of London municipal reform upon a sea strewn with many wrecks and whose shores are whitened with the bones of many previous adventurers’. (Hence the cartoon on the right.) What he faced was mass indifference, with an average of just 15 MPs turning up for the debates. Eventually, in 1888, the Local Government Act was passed, which created the London County Council a year later.

10/4/14 Gypsies at Hackney and Shoreditch

.jpg)

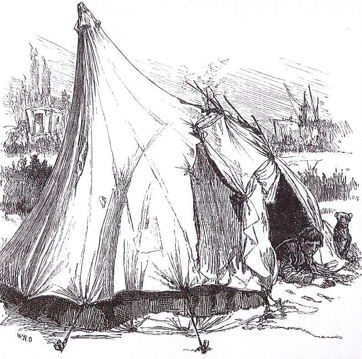

These drawings were done in the 1880s when some Romany folk came to rest temporarily on Hackney Marshes; the man top left is a knife-grinder, at work at his portable lathe.

In the late 19th century, certain parts of London and its surrounds were known for their gypsy encampments – including Wandsworth, Notting Dale and Epping. In the extract below, from his 1874 book Romano Lavo-Lil: Word-Book of the Romany; or English Gypsy Language, George Henry Borrow claims that many travelling people began to settle down in houses, abandoning life on the road. He identified the eastern part of the Old Nichol as one spot where this forsaking of canvas and caravans for bricks and mortar was taking place.

Borrow is mistaken, however, in thinking there was ever a friary on the spot (the area had been monastery land once, but ‘Friars Mount’ actually refers to the fact that a farmer called Fryer had tilled the land in the 18th century). And he over-emphasises the criminality of the Nichol residents; and his anti-Catholicism is at full volume here.

‘Not far from Shoreditch Church, and at a short distance from the street called Church Street [now Redchurch Street], on the left hand, is a locality called Friars Mount, but generally for shortness called The Mount. It derives its name from a friary built upon a small hillock in the time of Popery, where a set of fellows lived in laziness and luxury on the offerings of foolish and superstitious people, who resorted thither to kiss and worship an ugly wooden image of the Virgin, said to be a first-rate stick at performing miraculous cures. The neighbourhood, of course, soon became a resort for vagabonds of every description, for wherever friars are found, rogues and thieves are sure to abound; and about Friars Mount, highwaymen, coiners and gypsies dwelt in safety under the protection of the ministers of the miraculous image.

‘The friary has long since disappeared, the Mount has been levelled, and the locality built over. The vice and villainy, however, which the friary called forth still cling to the district. It is one of the vilest dens of London, a grand resort for housebreakers, garotters, passers of bad money and other disreputable people, though not for Gypsies; for however favourite a place it may have been for the Romany in the old time, it no longer finds much favour in their sight, from its not affording open spaces where they can pitch their tents. One very small street, however, is certainly entitled to the name of a Gypsy street, in which a few Gypsy families have always found it convenient to reside, and who are in the habit of receiving and lodging their brethren passing through London to and from Essex and other counties east of the metropolis.

‘There is something peculiar in the aspect of this street, not observable in that of any of the others, which one who visits it, should he have been in Triana of Seville, would at once recognise as having seen in the aspect of the lanes and courts of that grand location of the Gypsies of the Andalusian capital.

‘The Gypsies of the Mount live much in the same manner as their brethren in the other Gypsyries of London. They chin the cost [make clothes pegs], make skewers, baskets, and let out donkeys for hire. The chief difference consists in their living in squalid houses, whilst the others inhabit dirty tents and caravans. The last Gypsy of any note who resided in this quarter was Joseph Lee; here he lived for a great many years, and here he died, having attained the age of ninety. During his latter years he was generally called Old Joe Lee, from his great age. His wife or partner, who was also exceedingly old, only survived him a few days. They were buried in the same grave, with much Gypsy pomp, in the neighbouring churchyard. They were both of pure Gypsy blood, and were generally known as the Gypsy king and queen of Shoreditch. They left a numerous family of children and grandchildren, some of whom are still to be found at the Mount.

‘This Old Joe Lee in his day was a celebrated horse and donkey witch – that is, he professed secrets which enabled him to make any wretched animal of either species exhibit for a little time the spirit and speed of “a flying drummedary.” ’

There is more on Hackney Marshes and travellers in the 19th century, plus a fab photo, here: http://hackneycitizen.co.uk/2009/11/29/hackney's-place-in-the-romany-story/

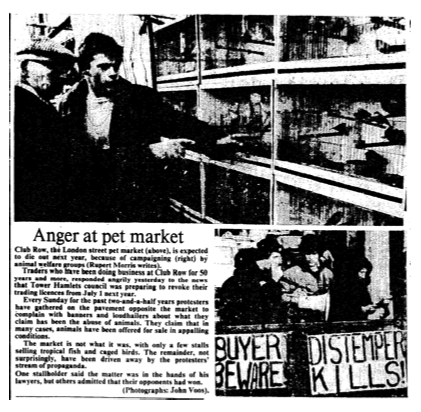

11/3/14 The last of Club Row

The great pet market at Club Row, immediately south of the Old Nichol/Boundary Estate, was shut down in 1983, after a protracted battle between animal-rights campaigners and market traders whose families had had pitches there for decades.

The first picture shows a dealer from the 1890s, who seems to be catering for the lovers of song-birds. For many of the poor,

a window box of plants and a bird singing in a cage were the only ways to import a little rus into the urbe. Pubs around the Nichol hosted song-bird competitions, with prizes for the loudest/most tuneful chirruppers.

The cuttings below the vintage pic speak for themselves, telling the story of the early 1980s battle to have the market closed.

15/2/14 Blackest streets up west. . . A letter to The Times

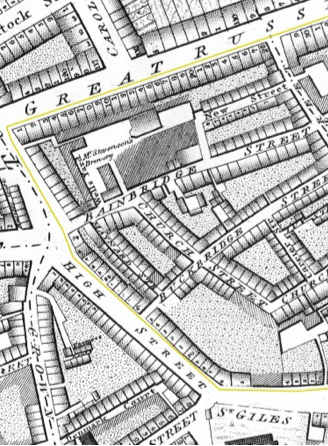

The St Giles slum just north of Covent Garden was one of the very poorest parts of London. This letter to The Times, printed in the edition of Thursday 5 July 1849, was a joint endeavour by locals to try to draw attention to their plight. This was two years before Charles Dickens made his famous tour of the slum with Inspector Field (http://www.djo.org.uk/household-words/volume-iii/page-265.html)

‘To the Editor of The Times

‘Sur, May we beg and beseech your proteckshion and power. We are Sur, as it may be, liven in a Willderniss, so far as the rest of London knows anything of us, or as the rich and great people care about. We live in muck and filthe. We aint go no privie, no dust bins, no drains, no water-splies, and no drain or suer in the hole place. The Suer Company, in Greek St, Soho Square, all great, rich and powerful men, take no notice watsomedever of our cumplaints. The Stenche of a Gully-hole is disgustin. We all of us suffur, and numbers are ill, and if the Colera comes Lord help us.

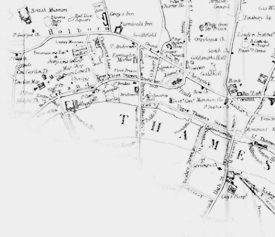

‘Some gentlemans comed yesterday, and we thought they was comishoners from the Suer Company, but they was complaining of the noosance and stenche our lanes and corts was to them in New Oxforde Street. They was much surprized to see the seller in No.12 Carrier St [see map above] in our lane, where a child was dyin from fever, and would not beleave that Sixty persons sleep in it every night. This here seller you couldent swing a cat in, and the rent is five shilling a week; but theare are grate many sich deare sellars.

‘Sur, we hope you will let us have our cumplaints put into your hinfluenshall paper, and make these landlords of our houses and these comishoners (the freinds we spose of the landlords) make our houses decent for Christions to live in.

‘Preaye Sir com and see us, for we are livin like piggs, and it aint faire we shoulde be so ill treted.

‘We are your respeckfull servants in Church Lane, Carrier St., and the other corts.

‘Teusday, Juley 3, 1849.’

John Scott; Emen Scott; Joseph Crosbie; Hanna Crosbie; Edward Copeman; Richard Harmer; John Barnes; William Austin; Elen Fitzgerald; William Whut; Ann Saunderson; Mark Manning; John Turner; William D Wyre; Mary Aiers; Donald Co.nell; Timothy Driscoll; Timothe Murphy; John O’Grady; Maria O’Grady; John Dencey; John Crowley; Margret Steward; Bridget Towley; John Towley; Timothy Crowley; John Brown; Catherine Brown; Catherine Collins; Honora Flinn; John Crowe; James Crowe; Thomas Crowe; Patrick Fouhey; William Joyce; Michal Joyce John Joyce; Thomas Joyce; John Sullivan; Timothy Sullivan; Cathrin Trice; James Regan; Timothy Brian; James Bryan; Phillip Lacey; Edward brown; Mrs. Brocke; Nance Hays; Jeryh Fouhey; Marey Fouhey; Jerey Aies; Timothy Joyce; John Padler.

12/1/14 The heroic vicar of Mount Street, Old Nichol

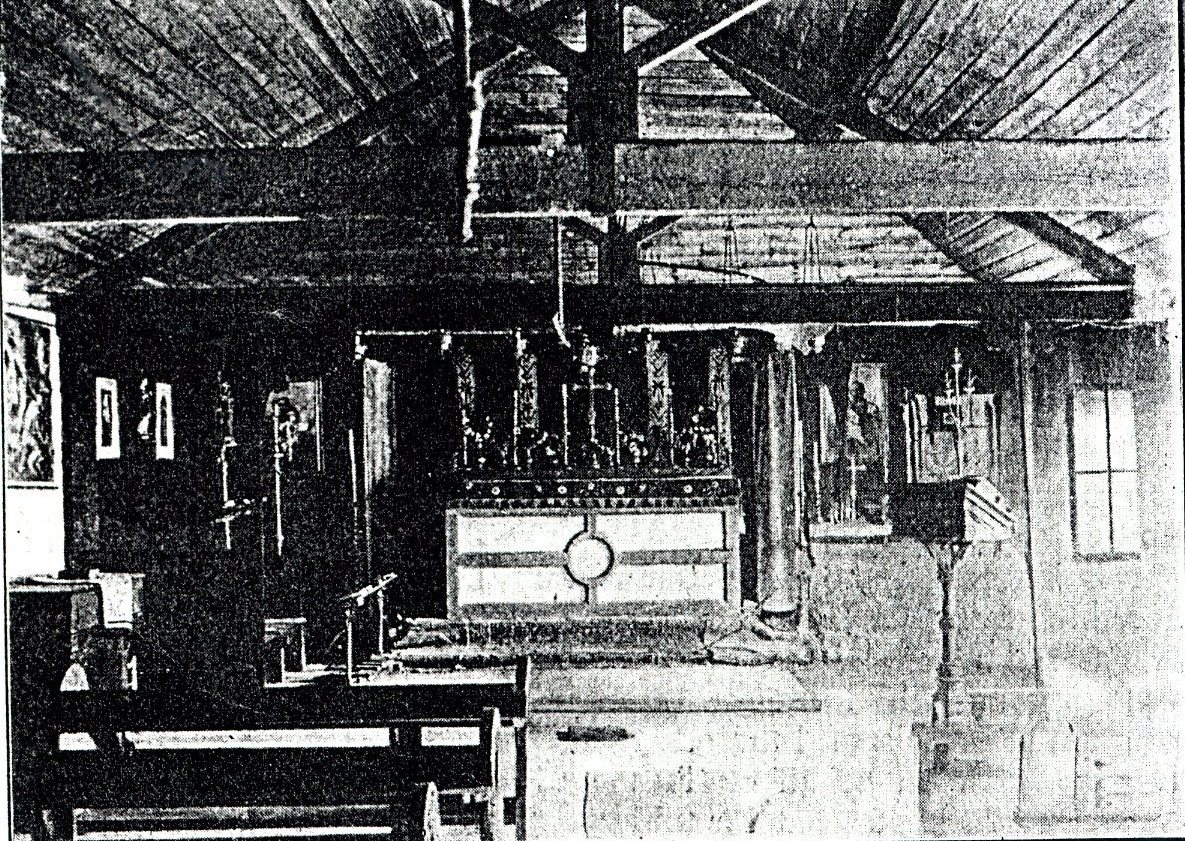

Peter Must is the great grandson of Reverend Robert Loveridge, the heroic but very modest vicar of St Philip’s, Mount Street (today’s Swanfield Street), who was scandalised by the publication of Charles Booth’s Poverty Map, in 1889: the depiction of the Old Nichol as a mass of black streets, indicating criminality, fecklessness and ineradicable chronic poverty, was, Reverend Loveridge said, ‘a malignant lie. . . the dwellers in the Boundary Street area were rather virtuous than otherwise’.

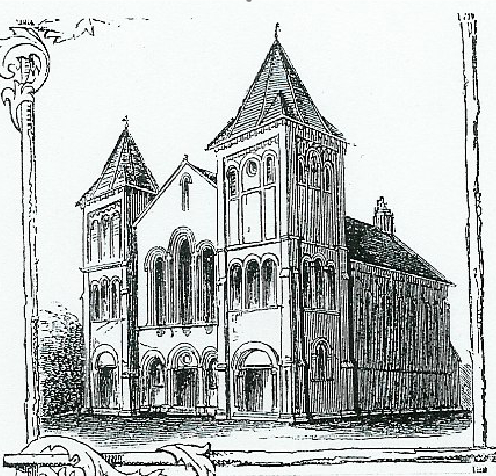

Sadly, no picture of Reverend Loveridge has survived, but one of his descendants, Peter Must, has written to me supplying some background information on the vicar and on his other Nichol ancestors. (Pictures of St Philip’s Church, now demolished, can be seen below, at the posting dated 4/5/13.)

Peter has written: ‘Robert Whatwood Loveridge was born in Bethnal Green in 1831, but was brought up in Birmingham. He married Caroline Brain, the daughter of a toll-keeper, and they had five daughters, of whom Ellen (Nellie), my grandmother, was the third. Caroline died, aged 33, in 1876 and the task of bringing up the children was shared by Caroline’s sister, Alice, and her husband, Henry Day.

Cambridge in the 1920s: Loveridge’s daughter is third from right; my correspondent’s parents are fourth from left and furthest right.

‘My grandfather, Henry Must, was born at 6 Christopher Street, in the Old Nichol, to James Must, a dock labourer who was himself born just south of the Old Nichol in James Street, later renamed Chilton Street [just east of Brick Lane].

‘Henry Must was baptised by Reverend Loveridge in St Philip’s in 1870 and was one of six siblings. In early 1891 he was a boot and shoe warehouseman but shortly afterwards entered theological college through the sponsorship of Rev Loveridge. He was ordained in 1893 and in 1895 married Nellie Loveridge, the reverend’s daughter. He became curate at St Philip’s in 1896 and succeeded his father-in-law as vicar in 1898. Subsequently he was for 37 years vicar of St David’s, Holloway, dying in 1942, two years before Nellie, who knew that my mother was expecting, but did not see me born.

‘Grandma Nellie always walked a few paces behind her husband and appears to have never been photographed without a cloche hat on.

‘Auntie Minnie, meanwhile (one of Reverend Loveridge’s other daughters), was a kindly spinster who looked after my sister and brother when they were ill and whose idea of entertainment was to seat them next to her at the piano while she bashed out and hollered “I’m H-A-P-P-Y!” and other rousing hymns.

‘While I am glad that Henry, and indeed all his brothers and sisters, escaped the “moral decay” that eugenicists might have predicted for him, I also like to think that his parents, James and Betsey, provided the best support they could for their children out of the meagre and sporadic wages available to a casual labourer.

‘My sister Brenda, who is ten years older than me, remembers Henry Must as a pretty strict disciplinarian, yet beloved by his parishioners; he was no doubt filled with the need to prevent his children sliding towards poverty and the workhouse (as his father and uncles had done) but also imbued by the sense of duty and care which I think was passed on by Reverend Loveridge.

‘James Must typifies the difficulties faced by the very poor. He and his family lived at various addresses in Mead Street and Christopher Street in the Old Nichol; they moved out by 1891, presumably as their accommodation came up for demolition for the building of the Boundary Street Estate, but travelling only a few hundred yards to a house in Granby Street [close to James/Chilton Street]. Betsey died in 1893 and (unable to cope on his own, I guess) James was thereafter an almost permanent resident of the workhouse, as indeed were his brothers William and Thomas, who had also lost their wives. He died in the infirmary in 1907, aged 75.

‘Your book provides heartening evidence to support Robert Loveridge’s view (was he thinking of his son-in-law’s family?) that the desperately poor of the Old Nichol were “rather virtuous than otherwise”. I sense you have some sympathy for the more chaotic, un-means-tested charity shown by Robert Loveridge. Loveridge was characterised rather snidely, as you point out, by his interviewer Arthur Baxter [part of Charles Booth’s survey team], a non-practising barrister of independent means – quite what “harm” Loveridge and others were doing, as Baxter claims, remains unclear.

‘For some obscure reason, Reverend Loveridge accepted the post of rector of Sigglesthorpe, East Yorkshire, after he left St Philip’s, but died there a year later, on 5 June 1899. Unfortunately, I do not have any picture of him, although I have this frustrating belief that there must be at least one image of him out there somewhere. He appears from your researches to have been a man suffused with charity almost to the exclusion of self-interest, or even objective reason.

‘As for many descendants of families who passed through the slums of East London, there is always a “What if. . .?” In this case, “What if the generation of Musts – who, in the late eighteenth century, thought the weaving trade in Spitalfields, Shoreditch and Bethnal Green offered better prospects than the placid but uncertain Sudbury, Suffolk – had decided against uprooting themselves and their families to seek that more prosperous life?” But of course, that question still resonates in the slums of Rio de Janeiro, Nairobi, Mumbai and elsewhere.

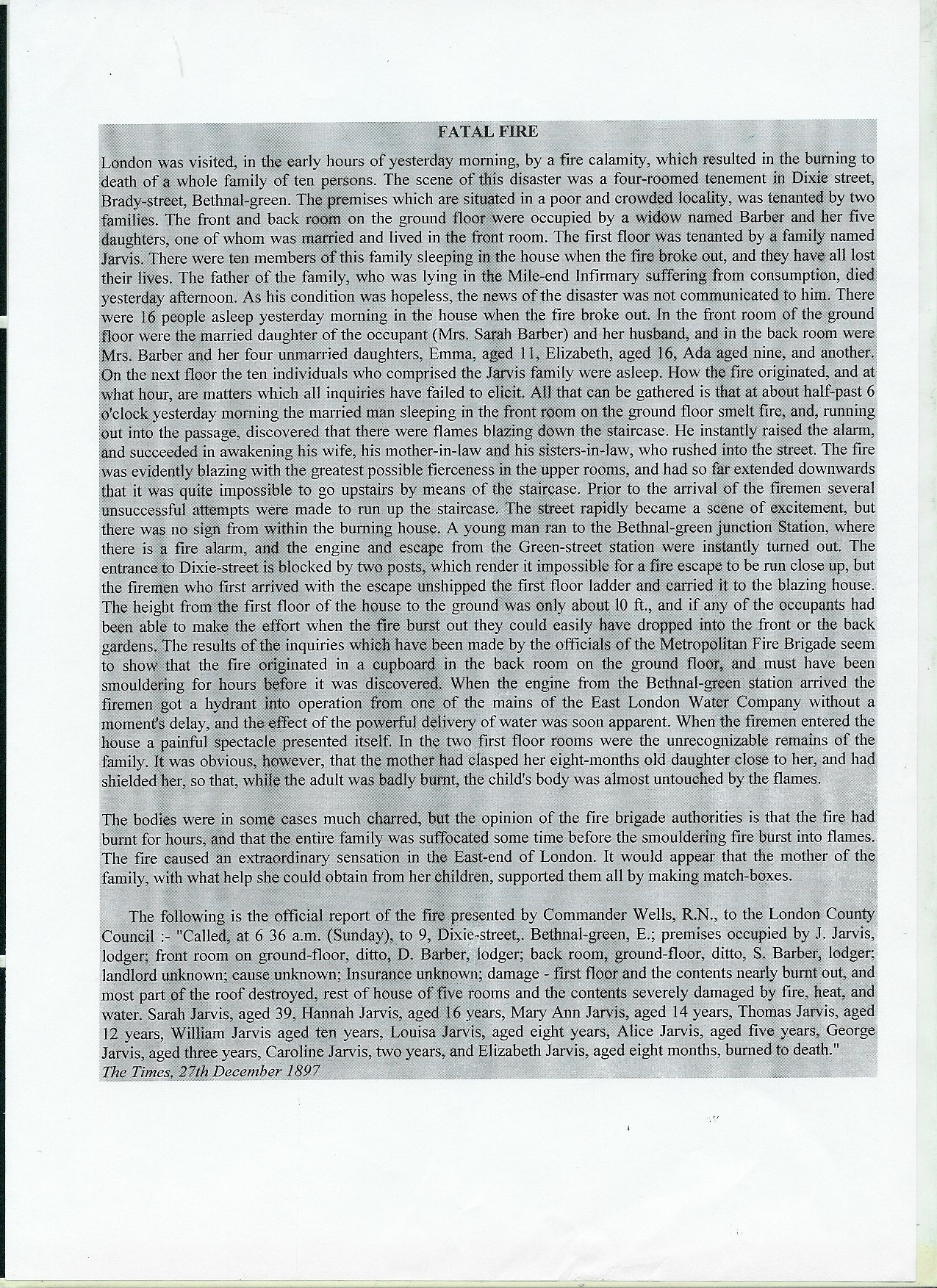

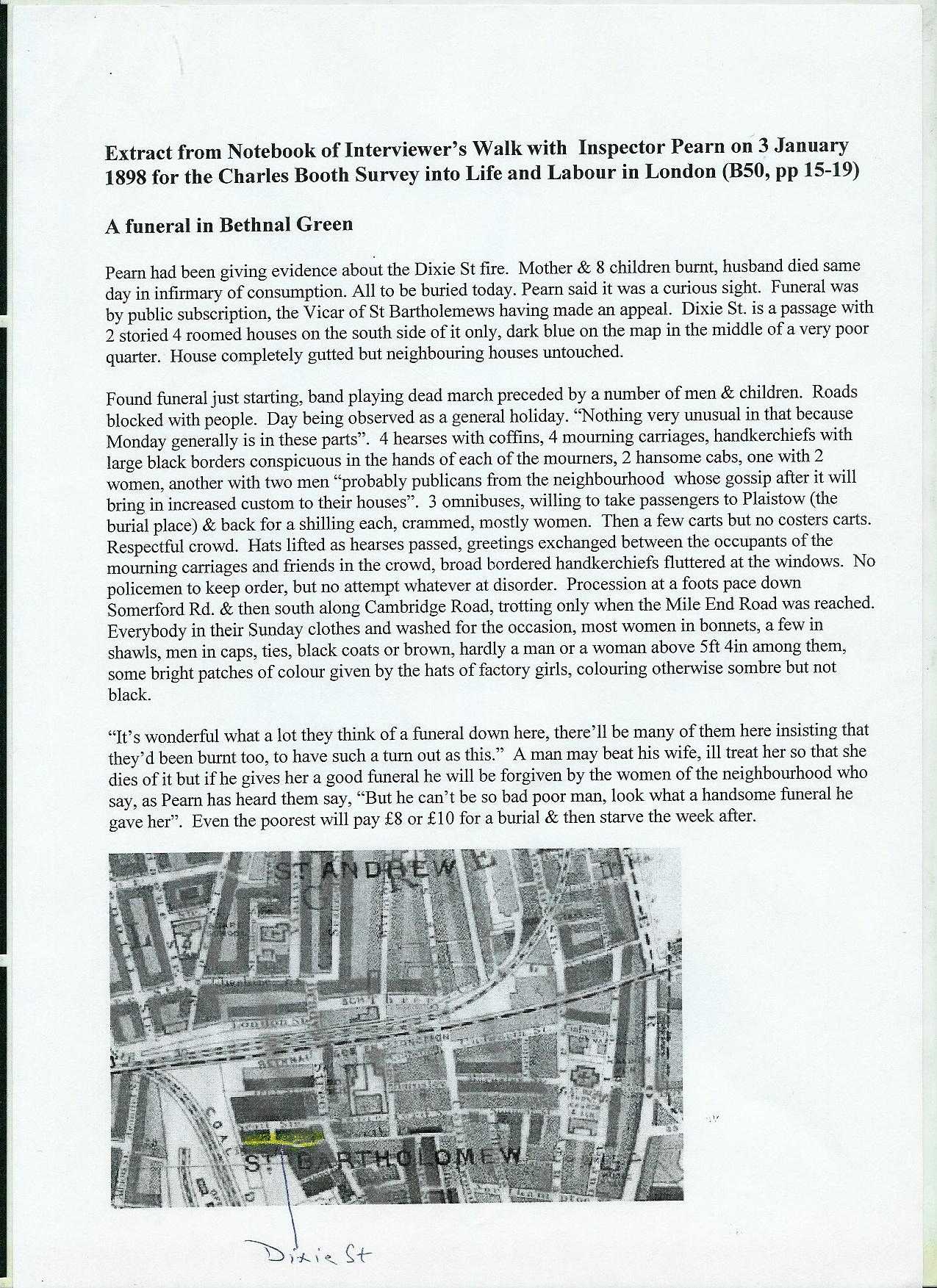

‘To finish off, we should perhaps contrast the life of Henry Must with the fate of his cousin, Sarah Ann. She was an early visitor to the workhouse, where her illegitimate daughter, also called Sarah Ann, was born and died. In that same year she married Thomas Jarvis, a matchbox-maker, and had nine children with him. What happened is chronicled in these documents. [Below: a newspaper cutting; a report from Booth’s survey notebooks; and a poem by William McGonagall.]’

‘Calamity in London’ by William McGonagall

’Twas in the year of 1897, and on the night of Christmas Day,

That ten persons’ lives were taken away,

By a destructive fire in London, at No. 9 Dixie Street,

Alas! so great was the fire, the victims couldn’t retreat.

In Dixie Street, No. 9, it was occupied by two families,

Who were all quite happy, and sitting at their ease;

One of these was a labourer, David Barber, and his wife,

And a dear little child, he loved as his life.

Barber’s mother and three sisters were living on the ground floor,

And in the upper two rooms lived a family who were very poor,

And all had retired to rest, on the night of Christmas Day,

Never dreaming that by fire their lives would be taken away.

Barber got up on Sunday morning to prepare breakfast for his family,

And a most appalling sight he then did see;

For he found the room was full of smoke,

So dense, indeed, that it nearly did him choke.

Then fearlessly to the room door he did creep,

And tried to arouse the inmates, who were asleep;

And succeeded in getting his own family out into the street,

And to him the thought thereof was surely very sweet.

And by this time the heroic Barber’s strength was failing,

And his efforts to warn the family upstairs were unavailing;

And, before the alarm was given, the house was in flames,

Which prevented anything being done, after all his pains.

Oh! it was a horrible and heart-rending sight

To see the house in a blaze of lurid light,

And the roof fallen in, and the windows burnt out,

Alas! ’tis pitiful to relate, without any doubt.

Oh, Heaven! ’tis a dreadful calamity to narrate,

Because the victims have met with a cruel fate;

Little did they think they were going to lose their lives by fire,

On that night when to their beds they did retire.

It was sometime before the gutted house could be entered in,

Then to search for the bodies the officers in charge did begin;

And a horrifying spectacle met their gaze,

Which made them stand aghast in a fit of amaze.

Sometime before the firemen arrived,

Ten persons of their lives had been deprived,

By the choking smoke, and merciless flame,

Which will long in the memory of their relatives remain.

Oh, Heaven! it was a frightful and pitiful sight to see

Seven bodies charred of the Jarvis family;

And Mrs Jarvis was found with her child, and both carbonised,

And as the searchers gazed thereon they were surprised.

And these were lying beside the fragments of the bed,

And in a chair the tenth victim was sitting dead;

Oh, Horrible! Oh, Horrible! what a sight to behold,

The charred and burnt bodies of young and old.

Good people of high and low degree,

Oh! think of this sad catastrophe,

And pray to God to protect ye from fire,

Every night before to your beds ye retire.

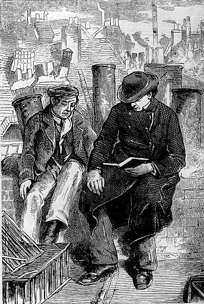

18/12/13 Churchmen and chimneypots – a Mary Poppins skyscape

In any overbuilt, cramped urban environment, roofs play a special role: fresh air and light being at a premium at ground level in a Victorian slum, the roof gave easy access to both. And that is why late-Victorian municipal school buildings often feature a rooftop playground.

In the Old Nichol, two churchmen made full use of the rooftop as a meeting place, in decent weather.

Above is an illustration of John Weylland, pastor with the London City Mission, preaching to one of his flock, from Weylland’s The Man With the Book (1877). Beyond them is the crazy skyline of Shoreditch chimneys, flues and smoke billows. All it needs is Dick van Dyke and his lucky sweeps.

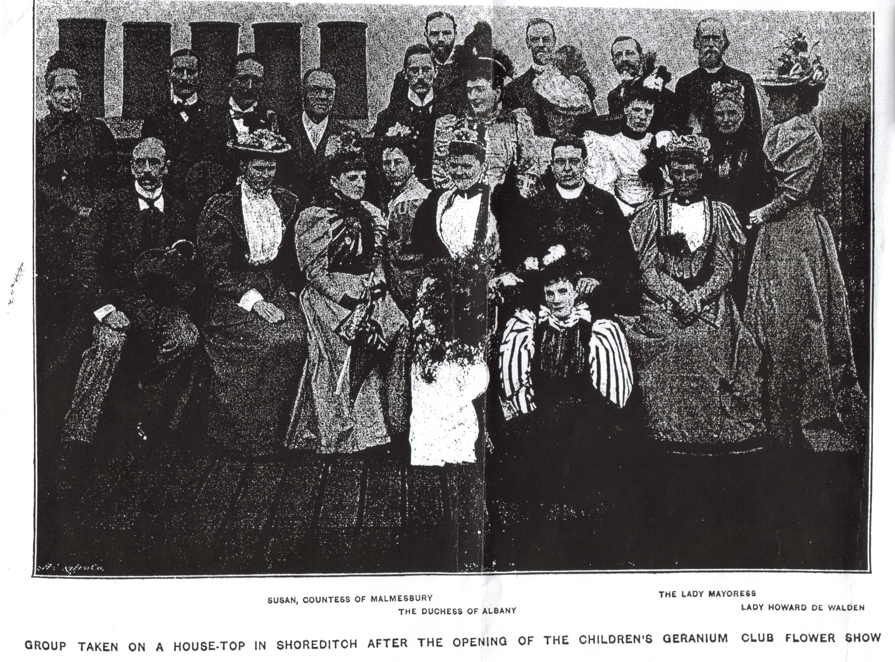

Below is Reverend Arthur Osborne Jay, tucked in among the leg-of-mutton sleeves and voluminous skirts of his titled lady sponsors (he is trapped 2nd row from front, 3rd from right). The shot was taken in June 1895

on the roof of his Holy Trinity Church, Old Nichol Street, to mark the second of his annual prize-givings for geranium growing.

Four hundred geranium cuttings in pots were bought using funds supplied by the Society ladies and gentlemen in the photograph, and given to the boys and girls of the two large local Board Schools.

The best specimens after three months won their growers prizes of books and workboxes. Jay reported that one little Nichol girl used to take her geranium out for a walk to get it some fresh air; another prize specimen bloomed in the room at 4 Old Nichol Street where the child’s father, James Muir, had murdered his common-law wife, Abigail Sullivan, in December 1891.

Jay had had his church and adjoining Model Lodging House designed with a ‘usable’ roof and from its four-storey height the Crystal Palace could be seen to the south, Alexandra Palace to the north, as well as St Paul’s cathedral and the towers of Charrington’s brewery in Mile End.

28/11/13 Stan Newens unravelling the Morrison mystery

As mentioned in the post below, novelist Arthur Morrison was mysterious about his early life. Stan Newens, former MP and local historian of London and Essex, broke new ground in 2008 with his biography of Morrison – Arthur Morrison: The Novelist of Realism in East London and Essex (Loughton & District Historical Society, £4.50).

Newens was also the person who originally introduced his constituent Arthur Harding to historian Raphael Samuel –

and that’s how the East End Underworld oral history project began (see posting of 19/2/13 below). Newens’s own autobiography, In Search of A Fairer Society: My Life and Politics, is published this week.

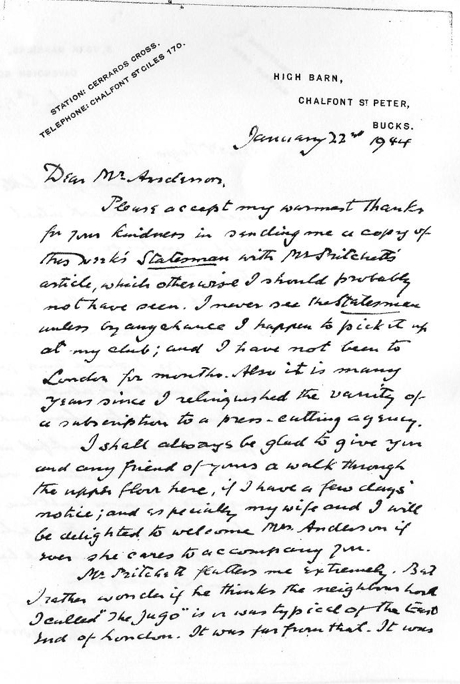

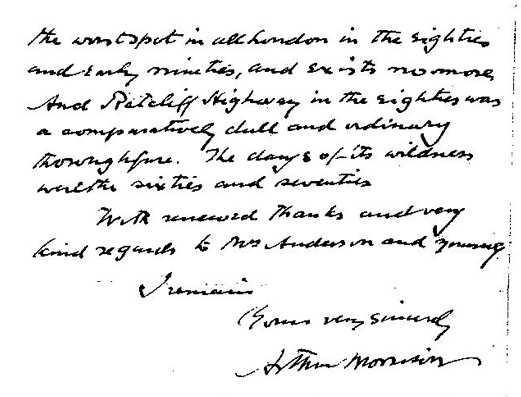

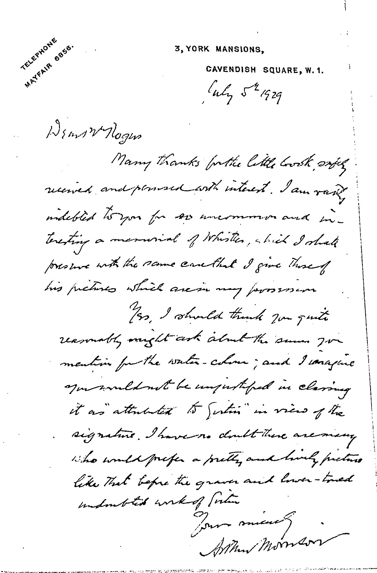

4/11/13 Arthur Morrison letters

Arthur Morrison’s novel A Child of the Jago (1896) is, among other things, the most impressive of literary re-brandings of a district in London history, perhaps even in world history. Morrison had exaggerated the awfulness of life in the real slum, the Old Nichol, and so powerful is his artistic vision, his fictional Jago has usurped the real Nichol in London imaginations.

We don’t know why Morrison chose to libel the Nichol population. Writing in the late 1960s, Morrison scholar PJ Keating stated that Morrison’s horror and loathing of the slum residents was probably attributable to some personal source. Morrison remains a rather mysterious figure. Interviewers failed to winkle much background information from him; and, as she had been instructed, Morrison’s wife, Elizabeth, burnt all his private papers upon his death in 1945. But we do know that he tried to blur the truth about his humble early years in Poplar. It is tempting to view A Child of the Jago as the work of a gifted, ambitious young working-class man putting a lot of distance between himself and those who had fallen into the abyss of chronic poverty.

Despite

the furore that A Child of the Jago caused (Morrison faced years of criticism for his attitude towards the slum dwellers), he remained unrepentant. In the first of these two letters below (bottom of first page and top of the second page), he continues to defend his take on the slum, to one Mr Anderson, who had written to him enclosing a cutting from the New Statesman in which commentator Mr Mitchell retrospectively praised his novel.

The second letter, dating from 1929, relates to Morrison’s second, and even more successful, career – as an art-dealer and connoisseur. Copies of both letters were very kindly given to me by Iain Sinclair, who found them during his second-hand book-dealing days.

16/10/13 London’s first council housing

The Boundary Street Estate (see stories below) is often described as the first council estate to be built in London. But in fact, Beachcroft Buildings (pictured below) – being smaller and less ambitious – was completed by the London County Council by September 1894. Boundary Street took ten years, from decision-making to opening ceremony (in March 1900).

Now demolished, the flats were just off the eastern end of Cable Street and housed 198 residents in two- and three-room tenements. The rent was higher than prevailing local private rental costs, at 5s 6d for two rooms and 7s 6d for three; and so – just as happened at Boundary Street – only the comparatively well-off working classes could afford to move in..

25/9/13 Rubble music: the sounds of old Shoreditch

Intrigued by the false hillock at Arnold Circus, on Shoreditch’s Boundary Estate, artist Thor McIntyre-Burnie sent a microphone probe down into the soil and created a site-specific sound installation. But let Thor explain for himself, here: http://measure.org.uk/exhibitions/rubble-music-thor-mcintyre-burnie

His website also contains a three-and-a-half-minute clip of the recording – sadly, no voices of Old Nichol children playing, nor the music of a barrel organ, nor the whelk vendor’s cry, nor any other 19th-century cockney soundscape. But the trains rumbling out of Liverpool Street do appear to be over-represented.

The image above shows the Estate, and its central mount, under construction in the mid-1890s; the view is looking east towards St Philip’s Church, halfway up Mount Street (today’s Swanfield Street). For the story of St Philip’s, see the posting dated 4/5/13, below.

The picture is part of a collection held at the London Metropolitan Archives, shelfmark 28.75 BOU.

http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visiting-the-city/archives-and-city-history/london-metropolitan-archives/Pages/default.aspx

Below: the Old Nichol, left, and the Estate, right, that was built upon its site. St Philip’s is on the right-hand edge of both maps.

18/9/13 School Dinners

This week’s announcement of free school meals for all children in the first three years of primary education was allegedly

prompted by evidence from pilot areas of a rise in concentration and achievement among those who were given free school

lunches. This phenomenon was recognised in the last years of the nineteenth century, and the schools of the Old

Nichol were instrumental in securing free lunches for all London schoolchildren. Lady Mary Jeune, below, was one of the London County Council’s first aldermen, but had begun her own political and social observation as a philanthropist, supplying food and clothing to the children of the Nichol. She was a co-founder of the Schools Dinners Association – which provided charitable free lunches for 36,000 schoolchildren. When Lady Jeune was elected to the LCC, she campaigned for the authorities to take over the feeding of London’s 750,000 schoolchildren from charitable bodies and church groups.

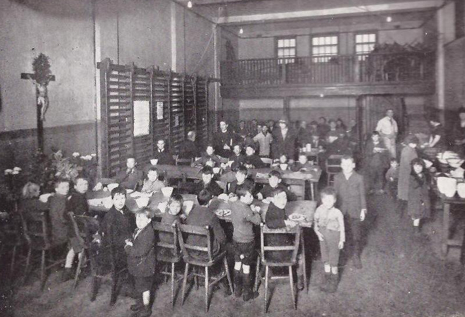

The 1886 illustration below shows the charitable feeding of the most destitute kids at the Old Nichol Street ‘Ragged School’ – the elementary school for the very poorest children. It’s highly stylised and can’t make up its mind if it wants to sneer at the infants or break its heart over them. At the Ragged School, breakfasts were served four days a week in the winter months, and comprised bread and butter, milk and cocoa. Around 100 to 120 of the neediest children were identified by the teachers and given tickets to come to be fed. Two days a week, lunches of bread and soup were served to the same children.

In addition, Reverend Loveridge of St Philip’s, Mount Street, and Reverend Osborne Jay, of Holy Trinity Old Nichol Street, provided hundreds of dinners in the winter months. But all these efforts were nevertheless inadequate, and in 1889 the London School Board reported that one in eight London school pupils was underfed. Testimony from teachers in the Old Nichol and other very poor areas indicated that hunger was impacting on the ability to learn. The reports of the Old Nichol teachers, held at the London Metropolitan Archives, are a desperately sad catalogue of the physical problems and the malnutrition that prevented slum children from being able to concentrate in the school room.

In addition, Reverend Loveridge of St Philip’s, Mount Street, and Reverend Osborne Jay, of Holy Trinity Old Nichol Street, provided hundreds of dinners in the winter months. But all these efforts were nevertheless inadequate, and in 1889 the London School Board reported that one in eight London school pupils was underfed. Testimony from teachers in the Old Nichol and other very poor areas indicated that hunger was impacting on the ability to learn. The reports of the Old Nichol teachers, held at the London Metropolitan Archives, are a desperately sad catalogue of the physical problems and the malnutrition that prevented slum children from being able to concentrate in the school room.

In 1889, the London School Board, which had initially been against public money being spent on school dinners, began to co-operate with the voluntary feeding of children as a prelude to full, rates-funded intervention. The Board discovered that the provision of meals boosted attendance, and in 1904 the parliamentary Interdepartmental Committee on Physical Deterioration came to the conclusion that the free feeding of all London schoolchildren was leading to higher rates of attendance as well as of achievement. The photographs below, of children from Lant Street in Southwark, were published by the Committee as ‘demonstrating’ that improvement had taken place.

As for the rest of the nation, in 1906 parliament passed The Education (Provision of Meals) Act, which permitted local authorities to lay on school lunches free of charge, though there was no obligation for them to do so.

Although the following passage from Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London survey may well not be referring to a Nichol school (it is named only as ‘A School in Bethnal Green’), it is a vivid eyewitness account of a charitable school lunch being served: ‘With the exception of a few small girls, all were poorly dressed and ill-nourished, but none were bare-footed. In Bethnal Green, however poor the children are, some foot covering is worn; it may be in holes, and simply absorb wet, but something they must have. One boy I noticed, as they filed out, had a pair of ladies’ dress slippers, with high heels and pointed toes; they had to be tied on across the ankle. Dinner was plentiful thick soup, with two slices of bread, followed by a slice of currant pudding put into the hands of each child as it left the building.

‘After grace was sung, the distribution of the soup began, it being ladled out of the copper into enamelled jugs by the caretaker, and taken round to the children by the girls. This took a few minutes, and whilst it was being done the impatient children were rapping the tables with their spoons, making a terrific noise. Gradually the spoons were diverted to their proper use, and some twenty minutes were occupied in consuming the food.’

And at another Bethnal Green school (again, not necessarily in the Nichol), this: ‘There were 48 of the boys at dinner – poor, thin, anaemic children – many of them very ragged; only three had collars. Chubby faces are scarce in this school. . .The children remain dull and difficult to teach. This, he [the headmaster] attributes partly to heredity, but still more to environment and especially to deficient nourishment.’

In the Nichol itself, a peculiar grace was sung by the children at charity lunches. It went:

‘I thank the Lord for what I’ve had,

If I had more I should be glad,

But now the times they are so bad,

I must be glad for what I’ve had.’

Further reading: School Attendance in London 1870-1904: A Social History by David Rubinstein (Hull), 1969. Charles Booth, Life and Labour of the People in London (Third Series: Religious Influences), 1902, pages 240-242. Archives of the Old Nichol’s schools at the London Metropolitan Archives have the shelfmarks LCC/EO/DIV5/ROC/AD/001 to 007, and LCC/EO/DIV5/NIC/LB/1 to 3, and LCC/EO/NEW/LB/1 to 6.

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1. Tel: 020 7332 3820

www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visiting-the-city/archives-and-city-history/london-metropolitan-archives/visitor-information/Pages/default.aspx

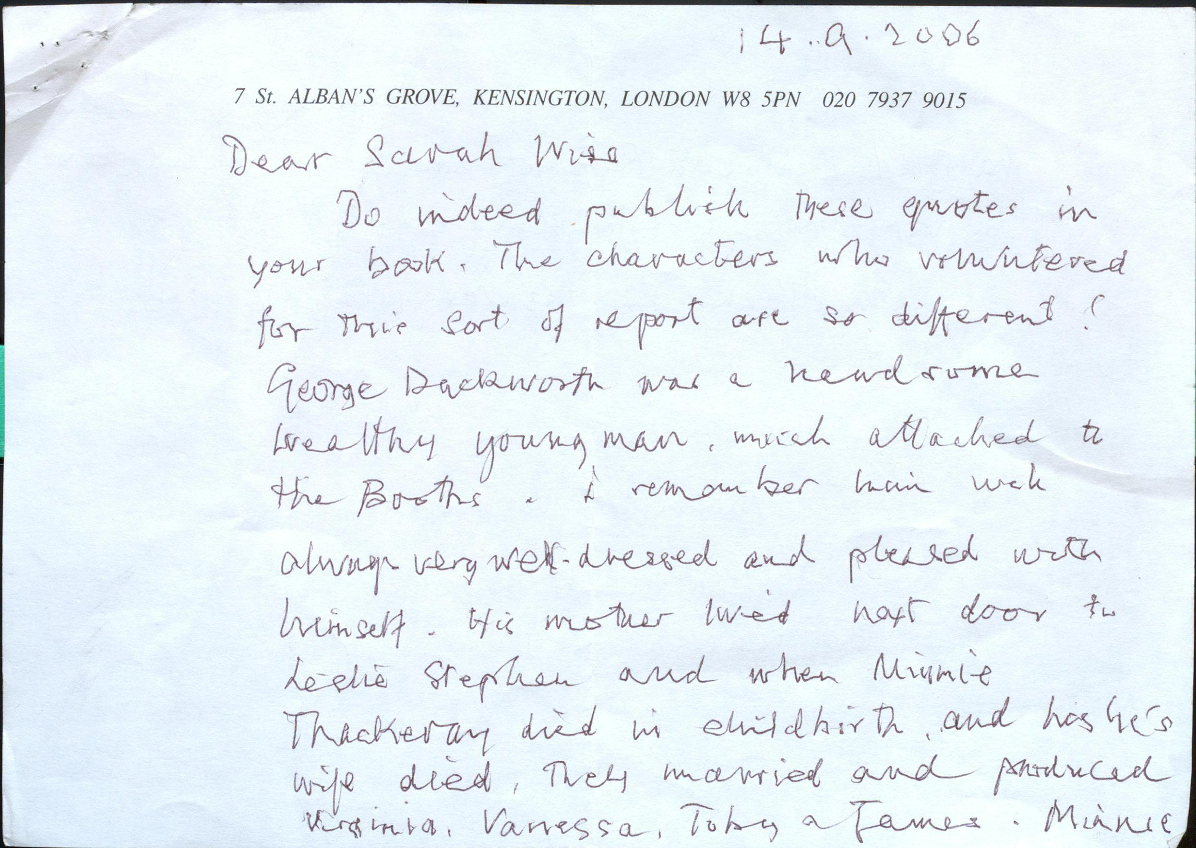

3/9/13 A letter from Charles Booth’s granddaughter

Belinda Norman-Butler (1908-2008) was Charles Booth’s granddaughter and author of Victorian Aspirations, a biography of Charles and his wife Mary. Back in 2006, before getting stuck in to the Booth Archive (I wanted to use extensive quotations in The Blackest Streets), I sought permission from Mrs Norman-Butler to quote from the original notebooks written by her grandfather and his team of researchers for his monumental survey, Life and Labour of the People in London (1889-1903).

Mrs Norman-Butler phoned me in response to my letter, and during our conversation told me her childhood memories of her grandfather (Charles Booth died in 1916). I found it amazing that I was having a conversation with someone who had had a conversation with Charles Booth.

I treasure the letter she sent me (written after she had broken her wrist in a fall), in which she mentions other relatives and literary acquaintances of yore; and I thank her relations, Catherine Wilson and Richard Martineau, for permission to publish it, below.

Above left: Belinda Norman-Butler with her grandmother, Mary Booth, in 1936. Both these photographs are to be found in Mrs Norman-Butler’s biography Victorian Aspirations: The Life and Labour of Charles and Mary Booth (1972).

20/8/13 A post-Blitz vision of London

Architect Charles Canning Winmill (1865-1945) designed some of the loveliest of the Boundary Street Estate blocks when the Old Nichol was demolished – Molesey (1896), Clifton (1897), Laleham and Hedsor (both 1898).

In 1900, Winmill, along with his boss, Owen Fleming, who had been in overall charge of the building of the Estate, moved from the Housing Department of the London County Council to its Fire Stations department. This is why the Euston Road fire station (below) looks so like Boundary, as do the Swiss Cottage fire station in Eton Avenue/Grove Road (1915), and Perry Vale in Forest Hill, south-east London (1902). (Winmill’s Red Cross Street station in Barbican is no longer standing.)

In the spring of 1941, Winmill wrote in a letter to his friend, Lady Jane Ferrers, a beautiful passage about revisiting London after a long time – and his feelings on walking through the devastation of the latest war damage: ‘This was in the nature of a pilgrimage to stricken London. You remember I went to Newgate Street, Christ’s Hospital, when I was ten – just 66 years ago. Later, I was articled in the City and spent many years in the service of London as a public servant, so I entered into the parts that had been devastated, as into the almost passion of the town, its suffering and its bravery. . . I was thoroughly nerved by the time I got near my old school, and, as I stood in front of Christ’s Church Passage, all I could see was the spire of the church standing, and the shell of the church.

‘Then I turned, and this time saw, for the first time in my life, St Paul’s from Newgate Street; if no one had been there I should have gone down on my knees. There was a sort of mist and smoke, and perhaps dust, but faintly above the cross and the dome were what seemed two eyes – these I at last made out to be the bright points on [anti-aircraft] balloons.

‘On towards Holborn, going west, I passed many places damaged. By this time it had become a sort of exaltation, and so throughout the day. If one could stand what I had seen, one could stand anything.’

Lady Jane replied: ‘Oh how I loved what you said of St Paul’s. I too have a war vision, from the top of a bus. Suddenly the ball and cross high in what one must call “the empyrean” – brilliant sun, and all around a thickish fog. So immutable it looked to me, and so it must have done to you – all the more for wandering through devastation as you did. What a dream walk!’

Further reading: Joyce M Winmill, Charles Canning Winmill: An Architect’s Life by his Daughter (1946)

A picture of the Swiss Cottage fire station can be seen at http://474towin.blogspot.co.uk/2008/06/from-look-out-to-full-blown-fire.html

Of Perry Vale at http://www.sydenhamsociety.com/2010/11/a-history-of-perry-vale-fire-station/

And a selection of shots of the lost Red Cross Street station are on the gallery section of the London Fire Brigade website http://www.london-fire.gov.uk/LFBImageAndPhotoLibrary.asp

25/7/13 Growing Up Around the Bandstand (3): Billie Sivill

Billie was born on the Boundary Estate in 1932. Her parents, Jack and Alice Sivill, were fully involved in local politics and her mother became the mayor of Bethnal Green. Sivill House is named in honour of Alice and Jack – the Berthold Lubetkin-designed housing block on Columbia Road (in fact, it stands on the site of Nova Scotia Gardens, the site of the Italian Boy killings).

Here, Billie recalls her parents and their time on the estate:

‘Both Mum and Dad came from Lincolnshire, Mum from Billinghay and Dad from Coningsby. They married there, but when the slump came, Dad tramped down to Stevenage and found work as a navvy. As the years passed he finished up as a clerk of the works. He moved to London and was there for eight years before Mum joined him with her siblings – six brothers and a sister. They had a flat in Hoxton, top floor and bug ridden. Every night the flat-irons came out to squash the bugs as they crept up the walls from the flats below. There was an outbreak of smallpox and the borough medical officer called to see how the family were. He remarked how clean the flat was, with scrubbed floorboards, and said, “You’ve done wonders with this flat, but I have a better flat for you in Bethnal Green.”

‘So the family (Mum and Dad and the children, David, Dorothy, Jack and Pat) moved to 6 Cookham Buildings on the Boundary Estate. The flat had three bedrooms. I was the first to be born there, on 13 December 1932, and my sister in 1937, two days after the coronation of George VI, and she won a “coronation cot” – all red, white and blue, donated by the basket-maker in Calvert Avenue.

Billie’s mum up at the window of Cookham Buildings, and in the foreground, Billie’s dad and her brother, David.

‘After the war, Mum and some tenants restarted the old tenants’ association and they managed to get the London County Council to build them a hut. This was used for meetings, but also as a social club, where people of the Boundary Estate could come and chat, dance, play cards and billiards, and it was also somewhere for people who lived alone to have some conversation and company. They called the hut De Carte House, in memory of the man who started the original tenants’ association.

Billie’s mum and dad at De Carte House.

‘An elderly Jewish couple who lived at number 9 Cookham Buildings would ask us to turn on the lights and to light their fire on their sabbath. The Hillers, another Jewish family, who lived at No 1, were friends of ours, and during the war when food was rationed, Mum would knock on the pipe by the side of the kitchen sink to let Sarah downstairs know when a “cuppa” was ready. Sarah would do the same. Sarah’s son, Tony, writes music and won the European Song Contest with “Save Your Kisses For Me”, which he co-wrote.

‘There was a list on the landing of the flats saying whose turn it was to wash the landing and stairs to the next floor down. Everyone took their turn and it was never dirty. We never saw a broken window or graffiti on the walls. The head porter, Mr Heyho, was quick to spot any children who had chalk in their hands! There were really very few disagreements between neighbours, and any that did happen were quickly forgotten. It was a nice place to live.’

*******************************

‘Mum was on the Borough Council – she was voted in, in the west ward, in 1935 and she served until the boroughs were merged in 1965. Dad, too, served on the council, I believe initially as an alderman, but later by election in the west ward. They were both on many of the main committees and Mum was also a manager and governor of several schools. Both were very outspoken and didn’t suffer fools gladly or allow themselves to be sidetracked by anyone. In 1957, Mum was elected mayor of Bethnal Green, and my sister Dorothy was her mayoress.

‘The Dorset Estate off Hackney Road was opened while Mum was mayor, and it was named after the Tolpuddle Martyrs. Individual blocks were named after the men who were transported to Australia for forming a trades union. At a later date, the tallest block was named after Mum and Dad – Sivill House [below]. Thinking about it now, it seems appropriate, as our own home was always full of people!

‘Dad died in February 1970 and Mum ten months later. At both their funerals the members of the residents’ association, some very old, waited outside the hut to pay their respects. At Dad’s funeral all the brothers of Mum who were still alive thanked Mum and Dad for bringing them up. The most touching thing at Mum’s funeral was when our Jewish neighbour, Joe Weinberg, stood up and said, “Look around you and you will see a selection of people here today from all religions and colour. It’s like the United Nations, and that’s as Jack and Alice lived their lives.” I looked around the table, for I hadn’t really noticed – they were all just friends to us – and I found myself feeling very proud of Mum and Dad.

‘They were totally dedicated to the work they did in our home, on the council and on the Boundary Estate. I believe they did it with love and hard work, just as they lived their lives. Yes, I am very proud of both of them.’

© Billie Sivill.

To see some photos of the Lubetkin staircase inside Sivill House (Lubetkin also designed the Penguin House at London Zoo – you’ll spot the echoes), go to www.flickriver.com/search/sivill+house/

and http://flickrhivemind.net/Tags/architecture,sivillhouse/Interesting

10/7/13 ‘Well done, Mr Wise!’ (Sadly, not a relative of mine. . .)

The Anti-Vaccination movement of the late 19th-century had a particularly strong cell in the East End; in the Old Nichol, home to the poorest East Londoners, destitute parents faced cumulative fines for refusing to allow doctors to vaccinate their infants against smallpox.