6/3/17 The fire at Southall Park Asylum

Paul Lang, local historian and author, reports the events of the night of 13-14 August 1883, when fire broke out at a small private asylum on the western edge of London.

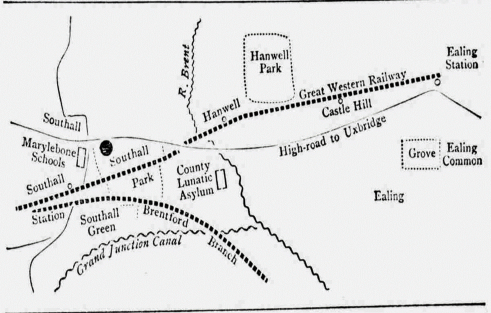

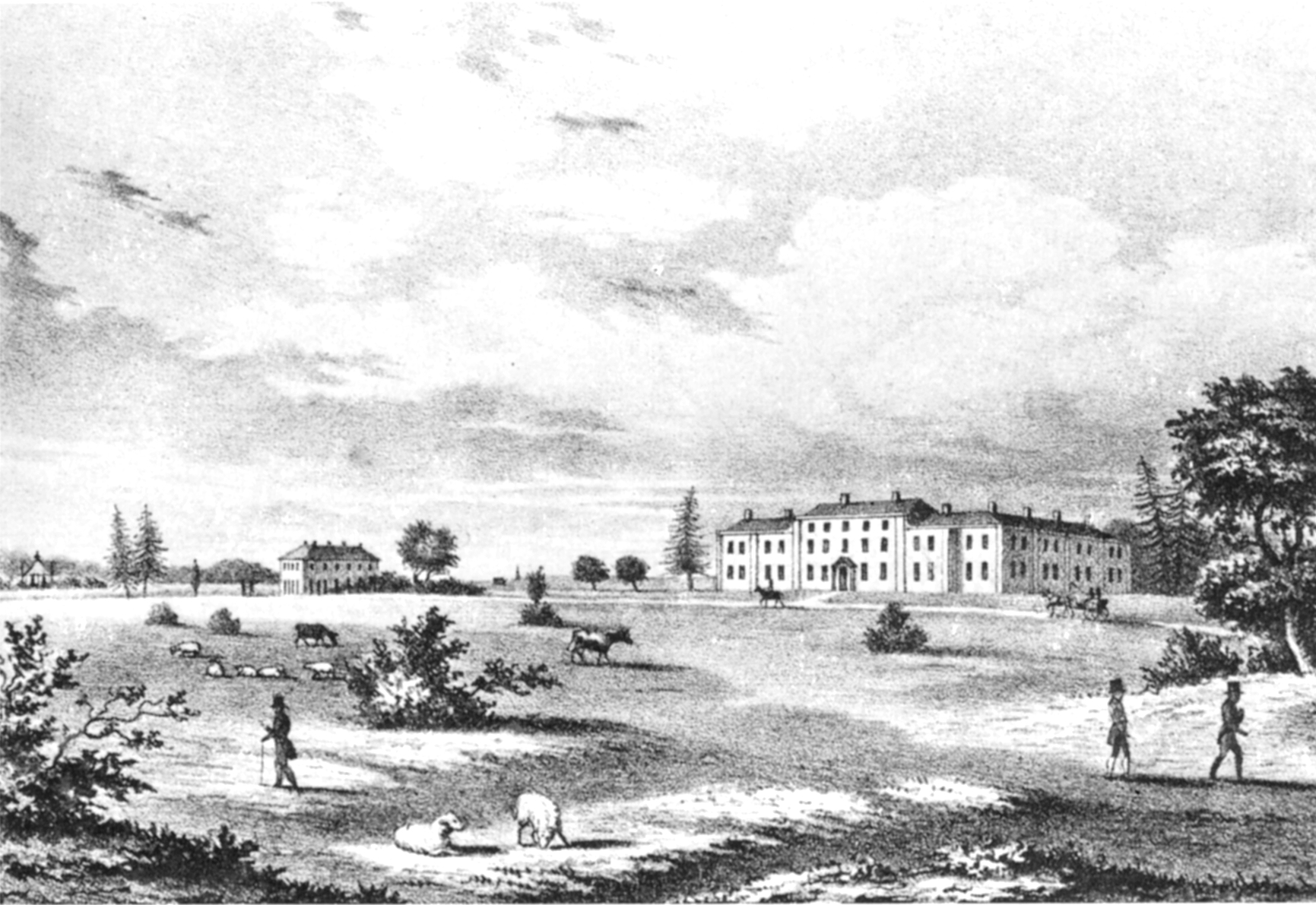

On the south side of the Uxbridge Road, in Southall Park, once stood a mansion. Originally known as Southall Park House, it was a distinguished building, designed in 1702 by Sir Christopher Wren for Sarah Jennings, the future Duchess of Marlborough. At the time of the fire in 1883, the house was owned by the Earl of Jersey.

The asylum was opened there in 1838 by Sir William Ellis, who died only a year later. Dr Ellis had been the first superintendent of the large Middlesex County Asylum, which was just half a mile to the east. The superintendence of Southall Park Asylum was continued by his wife, Lady Mildred Ellis, who had previously been matron at the county asylum. She supervised it until 1851, and in that year the Census reveals that the asylum had 7 servants, 8 attendants and a surgeon. It accommodated 7 female and 17 male patients. The latter included 4 clergymen, a soldier, 2 East India Company men, a surgeon and 4 gentlemen.

In 1861 Dr John Burdett Steward was in charge, and there were 11 male and 8 female patients. The males now included 2 Indian Army officers, 2 merchants, a solicitor and a Cambridge fellow.

Another smaller asylum, possibly an overflow establishment, was located just across the Uxbridge Road in North Road, not far down on the west side, and was known as The Shrubbery. (There is still a ‘Shrubbery Road’.)

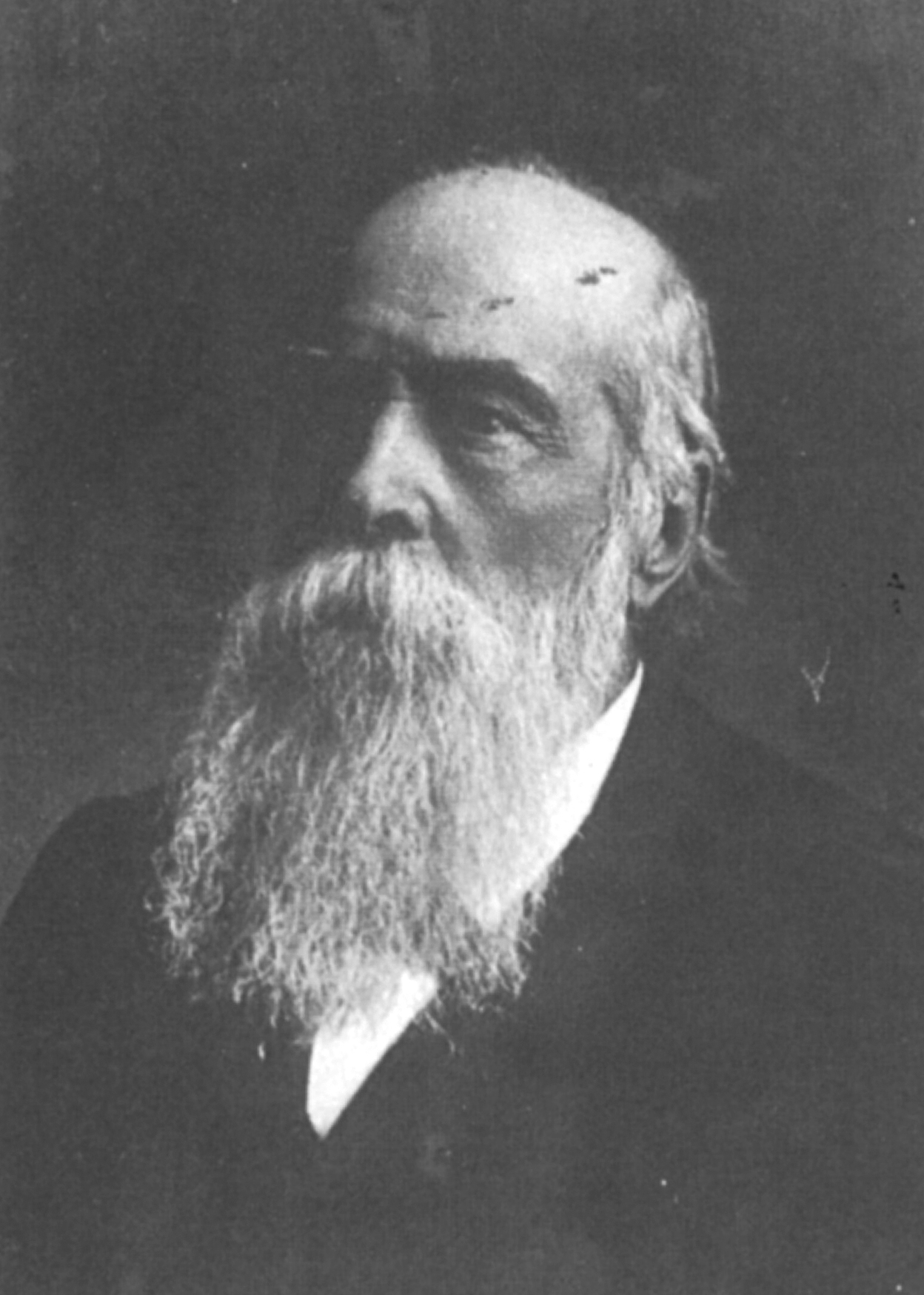

In 1871 Annie Steward, Dr Steward’s niece, was listed at The Shrubbery, along with 3 female patients, 5 servants and 3 relatives. In 1878 Dr John Steward was in charge of The Shrubbery and 70-year-old Dr Robert Boyd was the medical superintendent in charge. Dr Boyd was formerly superintendent of the lunatics’ ward at the Marylebone Workhouse, and afterwards at the Bath and Somerset Asylum. He wrote many articles on mental health, and was said to be a very kind person: in his seventies, he had once saved someone from drowning. On the night of Monday 12th/Tuesday 13th August 1883, he once again attempted to save life: as Southall Park Asylum went up in flames, Dr Boyd re-entered the building to rescue trapped patients and staff.

At the time there were 22 patients in his care — 9 male and 13 female. The fire was discovered by one of the female attendants, who raised the alarm.

One of Dr Boyd’s six children, William, who was grown up and visiting his father from America, also died in the fire, alongside two patients — Mrs Cullimore and Captain Williams — plus the asylum’s cook, Elizabeth O’Lachlin. (Captain Williams had been captured and tortured in Afghanistan during military service there, and this was said to have been the cause of his insanity.)

Mr Hatton, the gardener, jumped from an upper window, roughly 25 feet from the ground, breaking his arms and ribs and suffering serious concussion. He died later that day. Elizabeth Howe, the housemaid, injured her back and cut her head, and also later died of her injuries. Altogether seven people lost their lives.

Dr Boyd’s other son had had to jump from a window to escape the fire, and suffered a broken thigh. The doctor’s two daughters escaped via a fire escape on the west side of the building.

Mr Abbott, a local bee-keeper, helped rescue the patients who were trapped upstairs. They were brought to safety by means of ladders. Some of the patients had become totally rigid in fright, and so had to be forcibly removed. Three of the staff suffered foot injuries after jumping from the windows. Flames were pouring from every window of the house, and onlookers reported a dreadful sound of screaming.

Two women were trapped in the western tower, with the flames licking around them. The firemen had not yet arrived, so the onlookers were beginning to panic and ran around trying to find some way to save them. One of the trapped women was heard to cry ‘I am dying!’ A ladder was found and both women were brought down to safety.

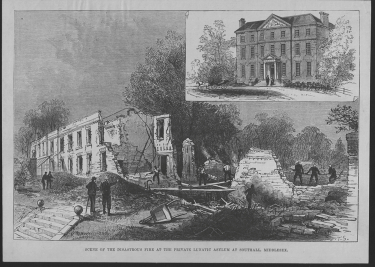

Southall did not have its own fire brigade at this point and so had to rely on the surrounding brigades. The Hanwell brigade was first on the scene, followed by Ealing, Ealing Dean, the Middlesex County Asylum’s brigade and one from Acton. The problem of fighting the fire was compounded by the fact that the nearest water supply to the asylum was a shallow pond a quarter of a mile from the house. When the firemen arrived they attempted to save the wings of the building, but they were almost completely gutted. Some of the walls had to be pulled down for safety, as they were in imminent danger of collapse.

The mansion was a complete ruin. On the Saturday after the fire a thorough search of the wreckage was made for the bodies of the missing; some 1,400 tons of building material was removed, which took nearly five days and 50 labourers. In one of the basement chambers next to the garden, the first human remains were found. Bones were found embedded in ashes which lay up to three feet deep.

The bones were examined by one Dr McDonald who believed them to be William’s remains. The burning roof and upper floor had fallen to the basement. It is believed that Dr Boyd and the other victims had suffocated due to smoke inhalation: the doctor’s daughters later revealed that the smoke had been so stifling that before they attempted to leave their bedroom, on the north side of the mansion, they had wetted towels, holding them to their faces before escaping along the corridor.

Later on, more fragments of bone were discovered and were thought to be that of the cook. In the north-east angle of the basement more bones were unearthed, which were believed to be the remains of Captain Williams and Mrs Cullimore.

After the fire, the ruins of the house remained standing for a considerable time. The cause of the fire was never properly ascertained. Boyd Avenue, the road leading to the western entrance of today’s Southall Park, is close to where the former asylum stood, and is a poignant reminder of this devastating incident and the heroism of Dr Boyd.

Paul Lang's book Hanwell and Southall Through Time has just been published by Amberley Publishing, £14.99

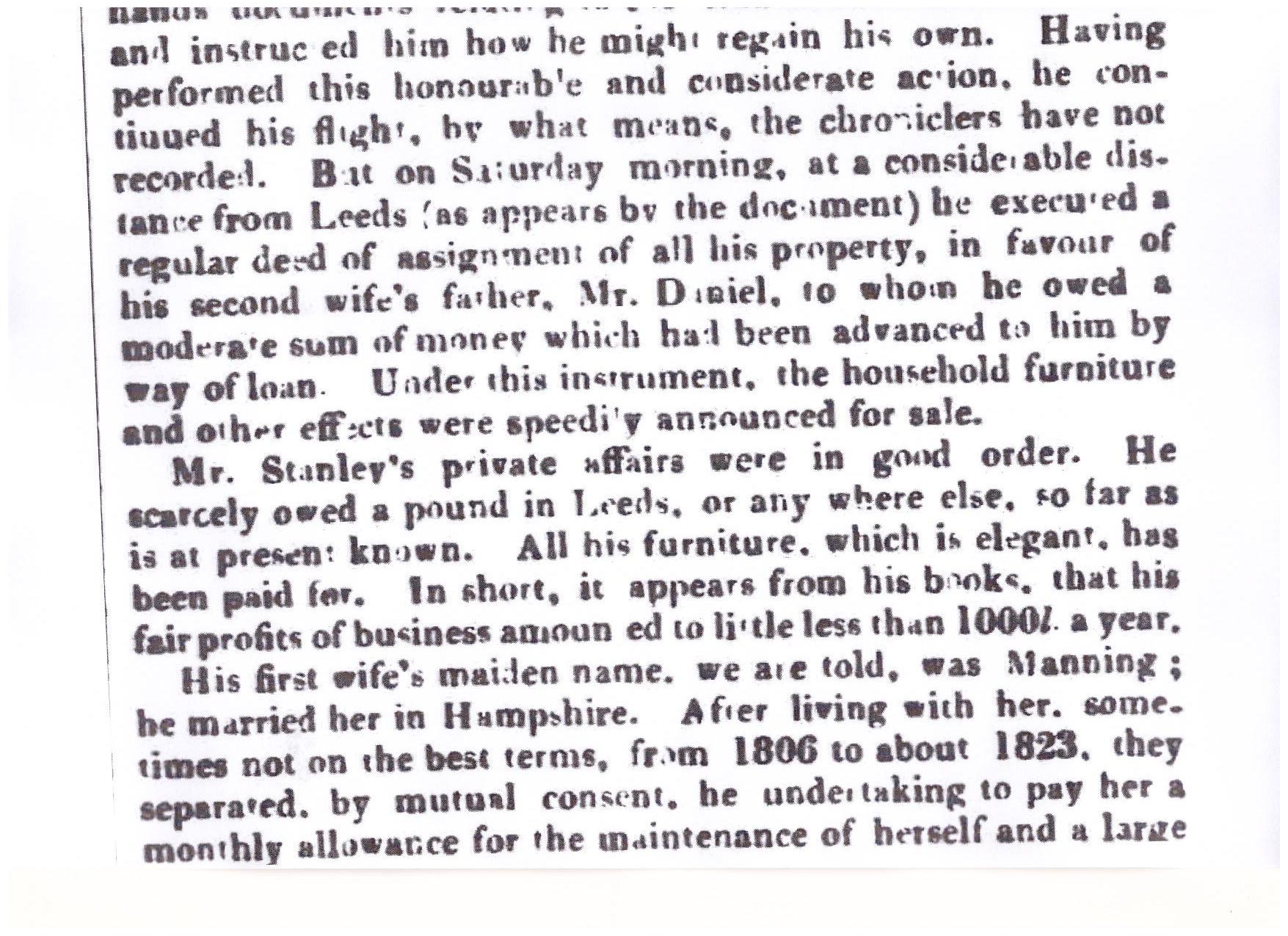

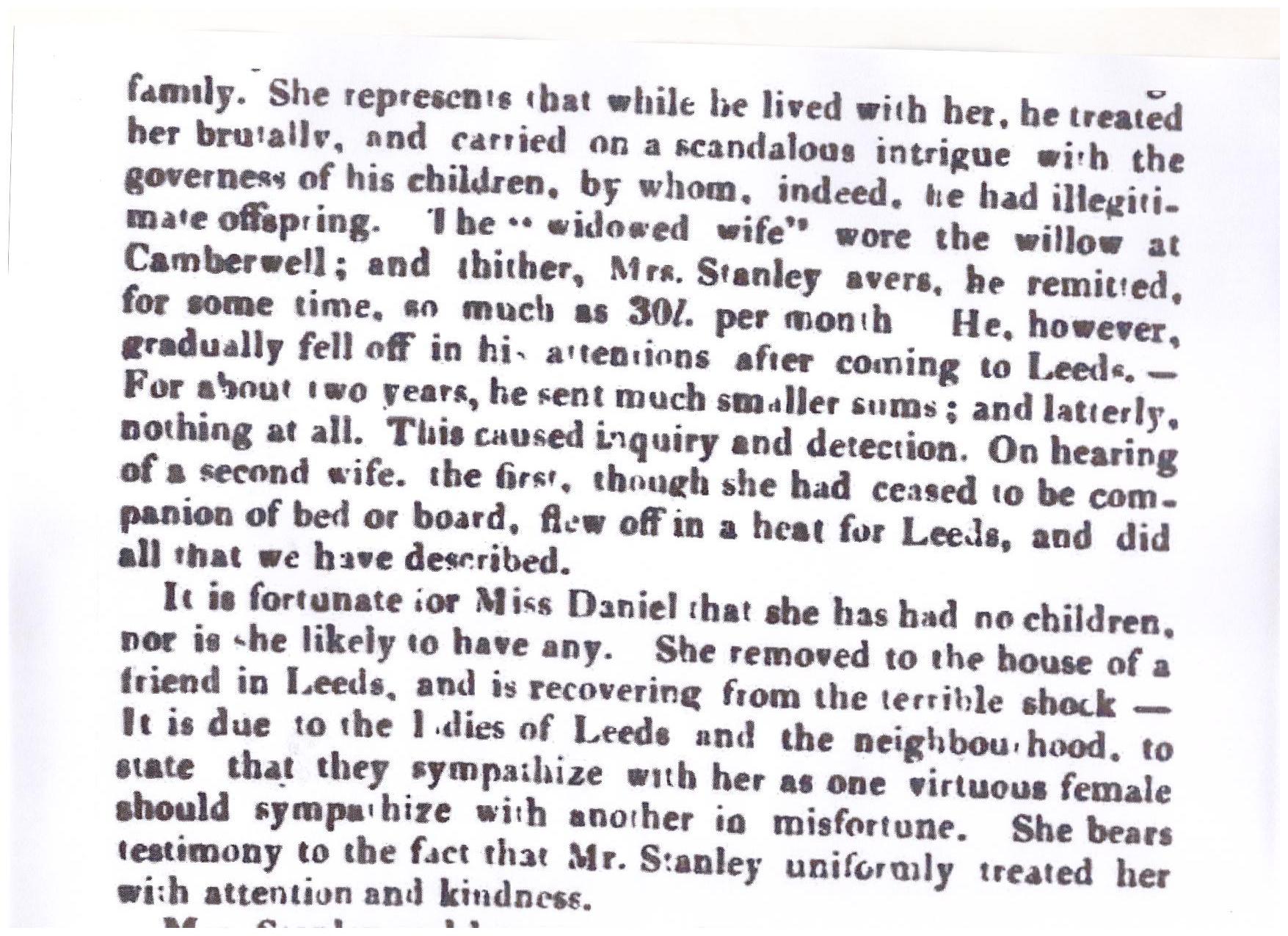

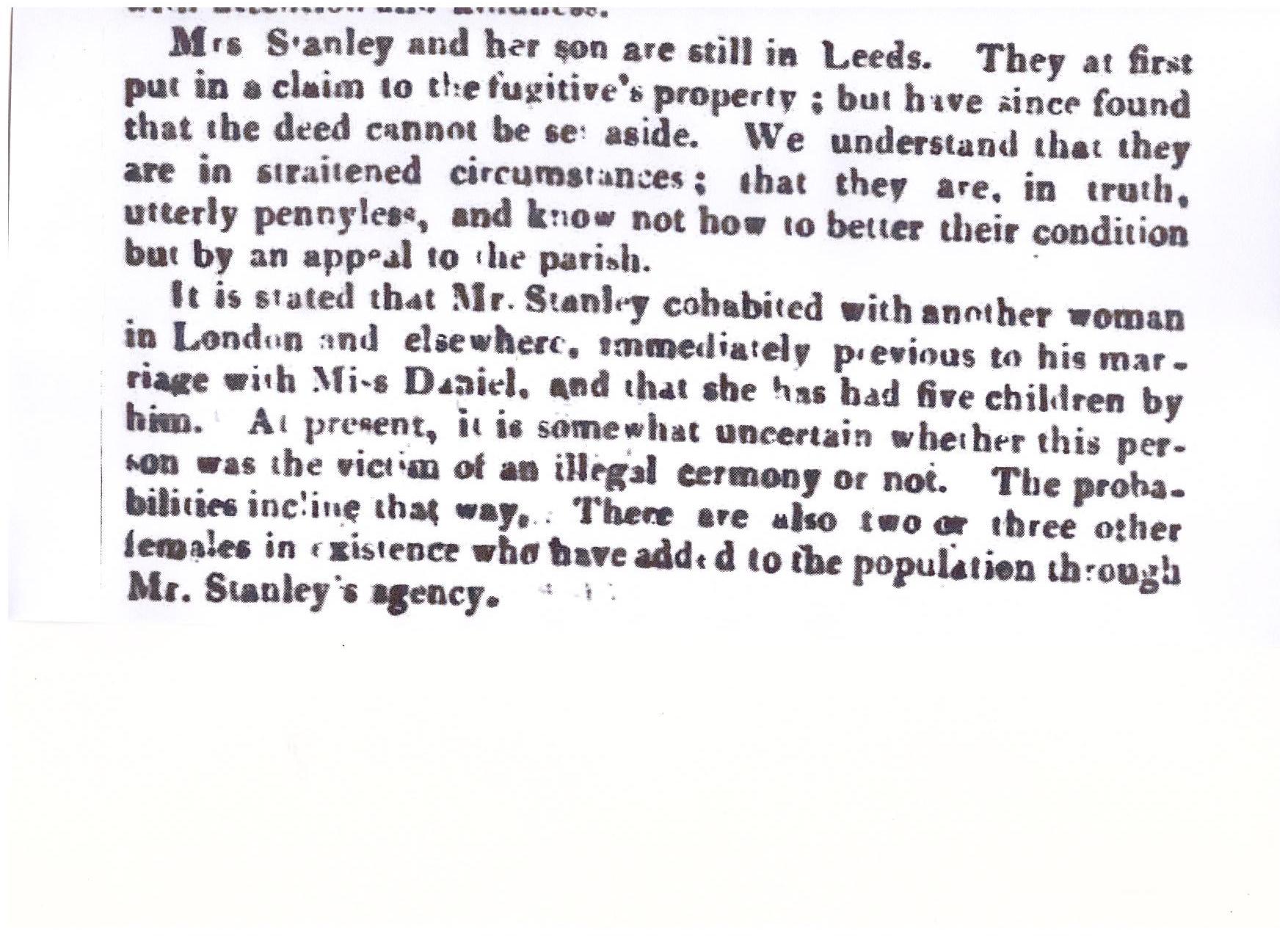

30/5/2016 Bronte, biography, Bertha: 'The Extraordinary Case of Bigamy at Leeds'

On re-reading Mrs Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Bronte (1857) recently, this passage jumped out at me:

‘It was about this time that an event happened in the neighbourhood of Leeds, which excited a good deal of interest. A young lady, who held the situation of governess in a very respectable family, had been wooed and married by a gentleman, holding some subordinate position in the commercial firm to which the young lady’s employer belonged. A year after her marriage, during which time she had given birth to a child, it was discovered that he whom she called husband had another wife. Report now says that this first wife was deranged and that he had made this an excuse to himself for his subsequent marriage. But at any rate, the condition of the wife who was no wife (of the innocent mother of the illegitimate child) excited the deepest commiseration; and the case was spoken of far and wide... Some of [Bronte’s] school friends consider that [this] incident which she heard when at school at Miss Wooler’s was the germ of the story of Jane Eyre. But of this nothing can be known, except by conjecture...’

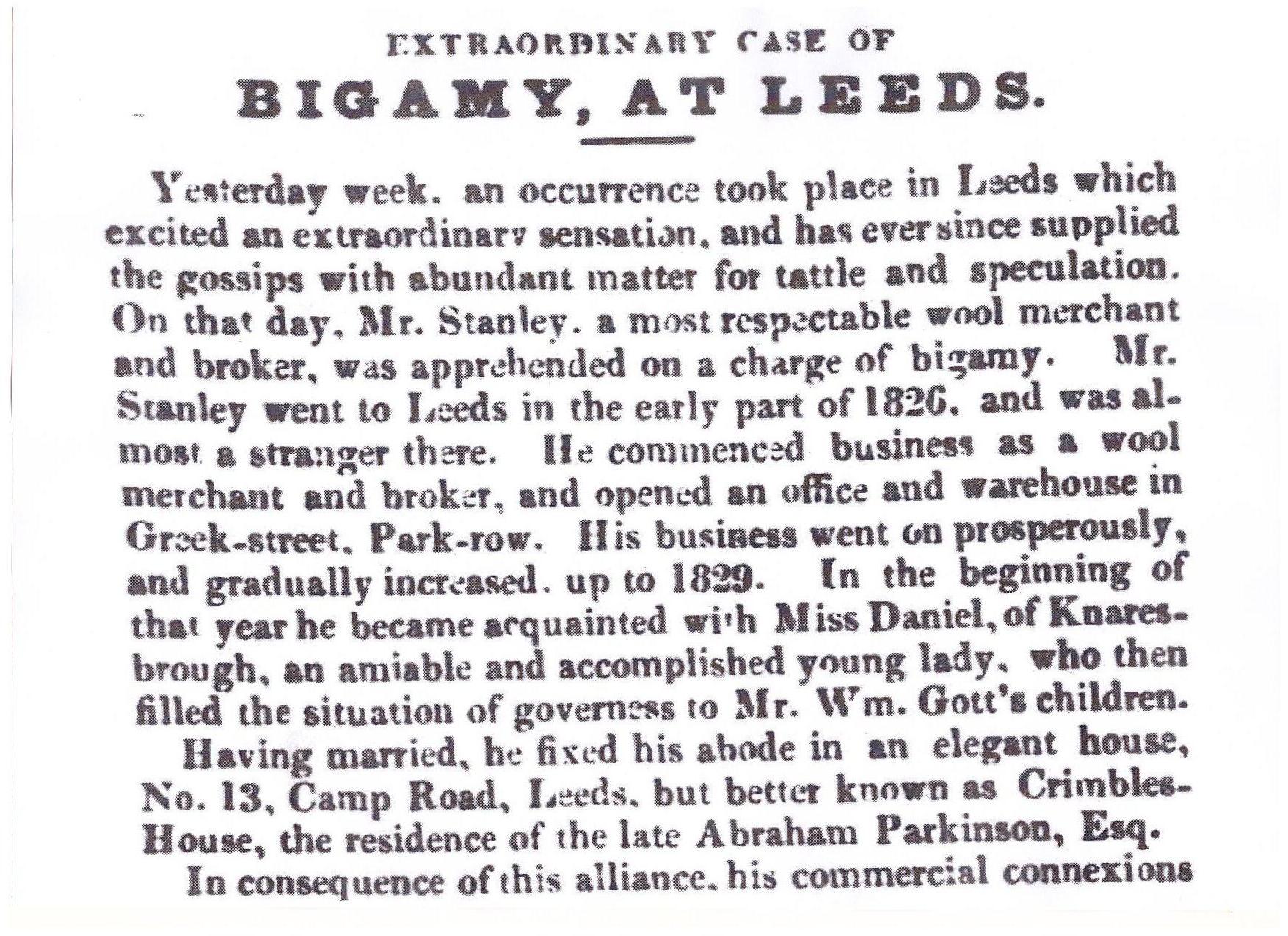

Reader, you will spot several differences between the above and the newspaper cutting below; but I’m going to stick my neck out and claim that this tale of John Stanley is the story that Bronte heard at Miss Wooler’s. I scoured the Assize Court records for the Leeds area in the 1820s and 30s; national and local newspapers; the National Archives, and I contacted the brilliant West Yorkshire Archive Service (thank you, Vicky Grindrod), and nothing else came close.

In his 1944 biography of Gogol, Vladimir Nabokov attacked the urge, among literary scholars, to seek out the ‘facts’ behind fiction:

‘It is strange, the morbid inclination we have to derive satisfaction from the fact (generally false, and always irrelevant) that a work of art is traceable to a "true story". Is it because we begin to respect ourselves more when we learn that the writer, just like ourselves, was not clever enough to make up a story himself? Or is something added to the poor strength of our imagination when we know that a tangible fact is at the base of the "fiction" we mysteriously despise? Or, taken all in all, have we here that adoration of the truth which makes little children ask the storyteller "Did it really happen"?...’

Love it. Now fast-forward 52 years, and here is Bronte scholar Juliet Barker, equally grieved that for certain folks, the Bronte sisters’ writings are often discussed in terms of ‘real-life’ characters and incidents which are somehow deemed to ‘explain’ their work. In a letter to the Sunday Times, published on 1 December 1996, Barker wrote: ‘The idea that there has to be a real original behind every person in the Bronte novels is an insult to their creativity.’

So I’m posting the cutting not because it reveals anything at all about Jane Eyre, but because it was a fun bit of detective work to do, and I think it’s an interesting story in itself (and sort of gruesomely amusing, too). Mr Stanley is not Mr Rochester; Miss Daniel is not Jane Eyre; but see what you think of the ‘Extraordiary Case of Bigamy At Leeds’ in The York Herald of 16 October 1830.

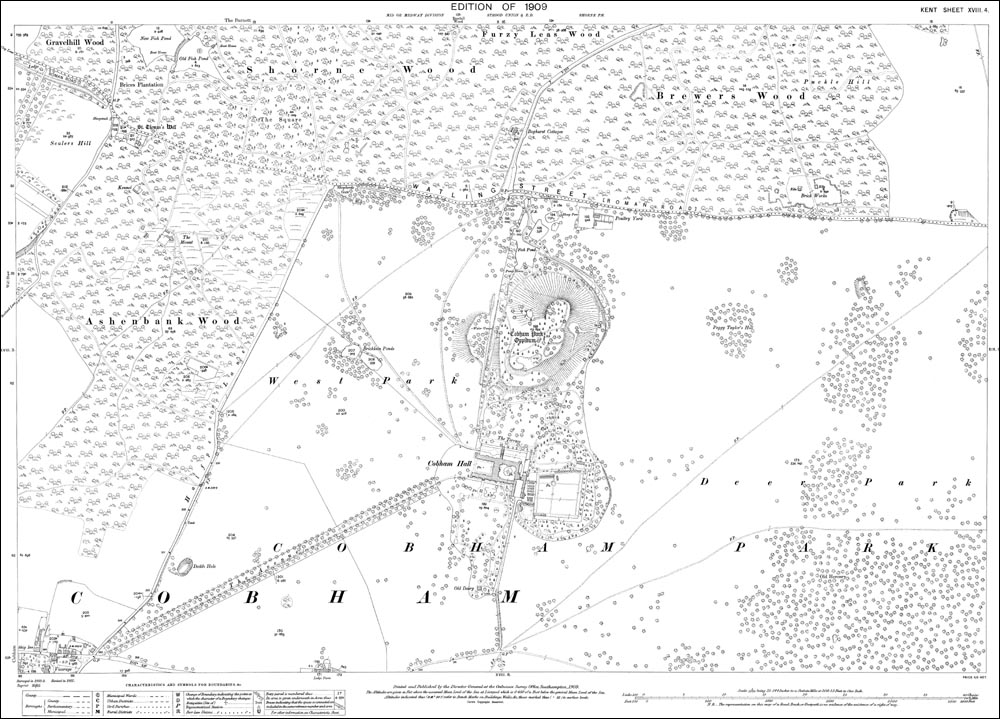

25/7/2015 Richard Dadd and Cobham Park

Richard Dadd, artist, began to suffer delusions in 1843; his father, Robert, however, was reluctant to consign him to the care of doctors. Overruling advice from Dr Alexander Sutherland, who believed that Richard would be dangerous when certain hallucinations came upon him, Robert took his son away from London to the Kent village of Cobham, in the hope that the countryside would calm him down and ease his psychological troubles. The pair stayed at the Ship Inn, pictured below (under scaffolding at the moment, for refurbishment).

But on 28 August 1843, on a walk in Cobham Park, Richard stabbed his father to death, believing that the Egyptian god Osiris had instructed him to do so. He fled abroad, attempted to stab a fellow traveller and was detained in France. On his return to England he was found unfit to plead and was sent to Royal Bethlem Hospital. He would remain in detention for the rest of his life, which lasted 43 more years.

The spot where the killing took place was, for about 100 years, called Dadd’s Hole. Charles Dickens, who was a near contemporary of Dadd’s and like Dadd had lived in Chatham as a child, would take friends to see the spot. The murder site lay just off the main roadway in the park (now a grassed over avenue) and the body had been easily spotted by a passer by.

Below are pictures of Dadd’s Hole (in long-shot and close-up), which is now fenced off due to very uneven and unstable ground; the long avenue that runs nearby, through the Park; and the 1909 Ordnance Survey map that shows the Hole, just above the ‘O’ of the lowest ‘Cobham’.

Below the pictures is my review of the current Dadd exhibition at the Watts Gallery near Guildford in Surrey. It’s the first major retrospective for many years and really not to be missed.

.jpg)

Review of ‘The Art of Bedlam: Richard Dadd’ exhibition at The Watts Gallery, published in

The Lancet, 11 July 2015

Perhaps more than is the case with any other artist, the appreciation of Richard

Dadd’s work is affected by knowledge of his biography. We scour each picture

for ‘meaning’ – for references to his killing of his father, for diagnostic signs of

incipient madness (in his pre-1843 creations) and of full-blown delusion in the

paintings that poured out of him during his 42 years in detention as a ‘criminal

lunatic’.

The complexity of Dadd’s ‘fairy’ paintings, in particular, can send the viewer off

into mundane and reductive musings. On the one hand, we might suppose, as we

gaze at Contradiction: Oberon and Titania (1854-58) or The Faery-Feller’s

Master-Stroke (1855-64), that lavishing such huge attention on microscopic

detail may be indicative of an obsessional mind; but then again, we can see that

the intricate planning and complicated, coherent storytelling show that Dadd’s

intellect was unimpaired for long stretches of time.

Dadd maintained a sense of humour, despite the horrific turn his life had taken: at the age of 26 he stabbed his father to death, acting on the instructions of the Egyptian god Osiris. Anticipating that people would try to read his paintings for indicators of his mental state, he wrote a long ‘explanatory’ verse about The

Fairy-Feller – which carefully revealed nothing. In this poem, he included the

line (echoing the masterpiece on vexed fatherhood, King Lear): ‘For nought and

nothing it explains and nothing from nothing nothing gains.’

The Watts Gallery show ‘The Art of Bedlam: Richard Dadd’ focuses on the works

produced before the artist’s July 1864 transfer to the new Broadmoor facility.

Upon being found not guilty of murder by virtue of insanity, Dadd was

committed to the criminal wing of Royal Bethlehem Hospital, where the eminent

doctors Edward Thomas Monro (1789-1856) and Alexander Morison (1779-1866)

oversaw his care. The Watts is itself a rather Dadd-like venue: a gem of a gallery

that you feel you have just tripped over in a dell deep in luxuriant Surrey

countryside – hidden away, like the faery world in the undergrowth. In its current

exhibition, all Dadd’s major phases are represented – the faery paintings, as

noted; the scenes inspired by his travels to southern Europe and the Middle East;

his fascinating series Sketches to Illustrate the Passions (1853-7); and two large,

linked oils, the first of Morison, an old man staring blankly from the frame, and

the second (below), an unnamed young man in an exotic, lush landscape, likely to be Dr

Charles Hood (1824-70). Dadd was in Bethlem Hospital during a time of

controversy and huge transition, and his paintings were eagerly ‘acquired’ by

both the under-fire old guard of Monro and Morison, as well as the new brooms

– Hood and head steward George Henry Haydon.

. Oil on canvas. Tate..jpg)

Dadd’s mental crisis had come on during his exhausting whistlestop Grand Tour of the Mediterranean and ‘Asia Minor’ in 1842/3. The bewildering range of

faces, terrains, costumes, ancient ruins and cityscapes provided him with years

of stored memories for paintings. The View of the Island of Rhodes (below) and The

Artist’s Halt in the Desert (both c. 1845) are likely to have been among the

earliest of Dadd’s Bethlehem pictures. The former shows the minutest of brushstrokes

detailing the parched rocks of the Greek island. The latter exemplifies a

Dadd-ian specialism – a vast, dark-blue night sky, pierced by moonlight, and in

the foreground a huddle of softly lit figures. (Halt, by the way, remains one of

the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow’s most stunning re-discoveries; having spent

decades unrecognised in a Barnstaple attic, it was bought in 1986 for £100,000 by

the British Museum.)

. Watercolour on paper. V&A.jpg)

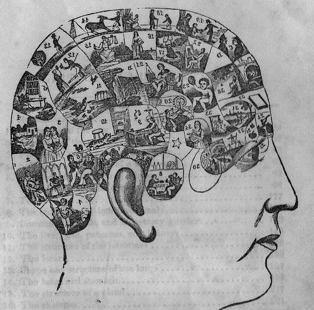

Several of Dadd’s Passions are on display – many of them are send-ups of his

carers’ own dabblings in the visual arts. Morison had been one of the first

British doctors to compile guides showing how particular mental ‘disease'

revealed itself in a patient’s face. (An illustration of a worried-looking woman

would be captioned ‘Religious Monomaniac’, and so on.) Artist Charles Gow,

who knew Dadd, came to Bethlehem to undertake physiognomical studies for

Morison. Dadd satirises such over-confident pathologising in such Passion

watercolours as Patriotism (1857), with two elderly sea-faring coves gazing

greedily at a map featuring imaginary locations that include ‘Great Pains Bay’ and ‘Island of Implication’. The faces that Morison found so easy to read for

illness, in Dadd’s works are ambiguous or inscrutable. As in the oeuvre of John

Tenniel (a near contemporary and one-time colleague of Dadd’s), characters

gurn, leer, express wide-eyed astonishment, ludicrous puffed-up fury, or

inexplicable haughtiness and froideur – they are funny and unnerving at the

same time. Just as in Tenniel’s illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s two Alice books, many of Dadd’s subjects seem locked into their own private world, not

interacting with each other, and blankly self-referential.

The exhibition also features archival material relating to Dadd’s confinement

and the institutional regimes under which his artistry actually thrived. Liberated

from caring what the public or potential art-buyers would approve of, Dadd’s

creativity found freedom behind bars.

The Art of Bedlam: Richard Dadd,

Watts Gallery, Down Lane, Compton, nr Guildford, Surrey UK,

until Nov 1, 2015

http://www.wattsgallery.org.uk

5/4/15 High anxiety: Henry Maudsley on the perils of being ‘civilised’

In his Pathology of Mind (1879) Henry Maudsley pondered (not triffically scientifically, it has to be said) why the ‘savage’ nations of the earth appeared to suffer less insanity than the populations in the developed world. It seems to me that what this passage actually gives away, as it reaches its crescendo, is how awful it was to be one of the ‘civilised’.

‘A question has been much discussed, and is not yet settled satisfactorily, whether insanity has increased with the progress of civilisation and is still increasing in the community out of proportion to the increase of the population. Travellers are agreed that it is a disease which they seldom meet with amongst barbarous peoples. But that is no proof that it does not occur. Among savages, those who are weak in body or in mind...are often eliminated... Certainly the weak units are not carefully tended as they are among civilised nations...

‘Admitting the comparative immunity of uncivilised peoples from insanity, it is not difficult to conceive reasons for it. On looking at any table which sets forth the usual causes of the disease, we find that hereditary disposition, intemperance and mental anxieties of some kind or other cover nearly the whole field of causation. From these three great classes of causes savages are nearly exempt...

‘On the other hand, it may be thought that the savage must suffer ill consequences from the unrestrained indulgence of his fierce sensual passions. But it might not be amiss to consider curiously whether savage nudity provokes sensuality so much as civilised dress, especially dress that is artfully designed to suggest what it conceals...

‘[And] the savage is not disquieted by fretting social passions: with him there is no eager straining beyond his strength after aims that are not intrisically worth the labour and vexations which they cost -- no disappointed ambition from failure to compass such aims, no gloomy dejection from the reaction which follows the successful attainment of an overrated ambition, no pining regrets, no feverish envy of competition, no anxious sense of responsibility, no heaven of aspiration, nor hell of fulfilled desire; he has no life-long hypocrisies to keep up, no gnawing remorse of consience to endure, no tormenting reflections of an exaggerated self-consciousness: he has none, in fact, of the complex passions which make the chief wear and tear of civilised life.’

16/1/15 San Servolo asylum in the Venetian lagoon

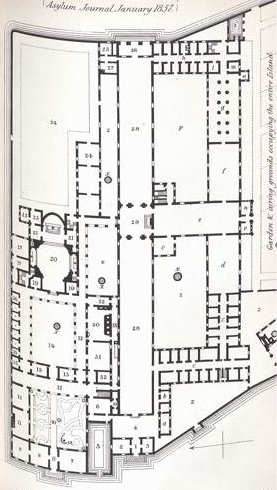

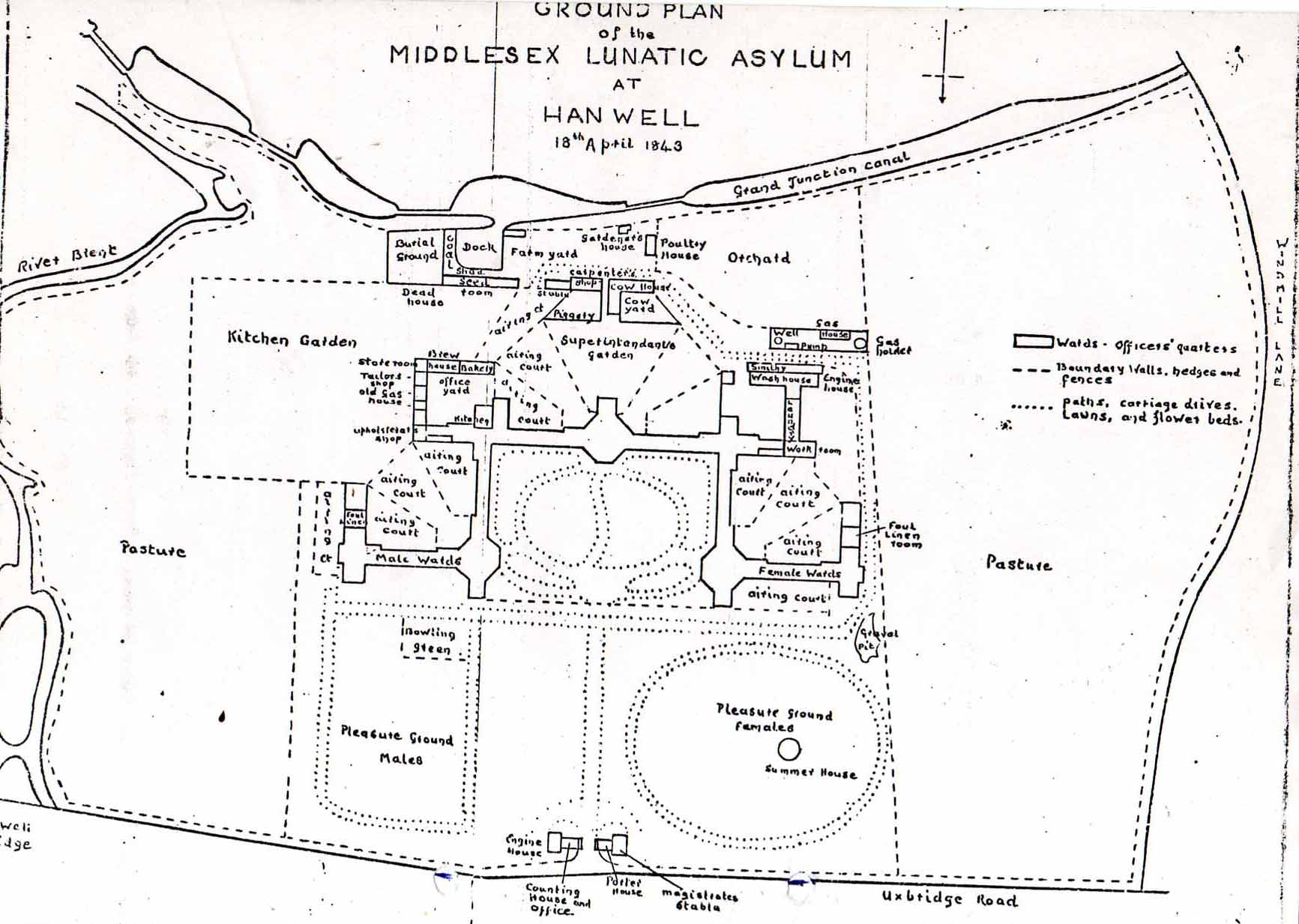

The Journal of Mental Science printed this floorplan of the asylum of San Servolo in Venice, along with a key to its plan and a table of the conditions and the social background of patients being admitted. The table makes one of the common 19th-century distinctions regarding the causes of mental breakdown, into ‘physical’ and ‘moral’ (ie psychological) categories.

‘Pellagra’ is Vitamin B deficiency; onanism is masturbation; ‘Migliare’ was a hereditary condition causing feverish inflammation of the lungs and intestines, and, it would seem, the brain.

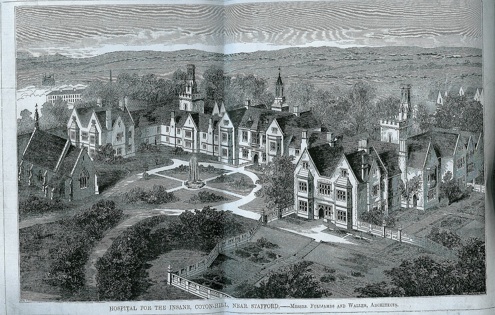

The layout and physical fabric of asylum buildings was of huge interest to the British government as it built and recconfigured its many state institutions for the insane.

Today, the building on San Servolo is a college and conference centre, with a Museum of Mental Health within the complex.

Contemporary colour image courtesy of San Servolo International College

http://virgo.unive.it/internationalcollege-studentswebsite/?one_page_portfolio=san-servolo-venice&lang=en

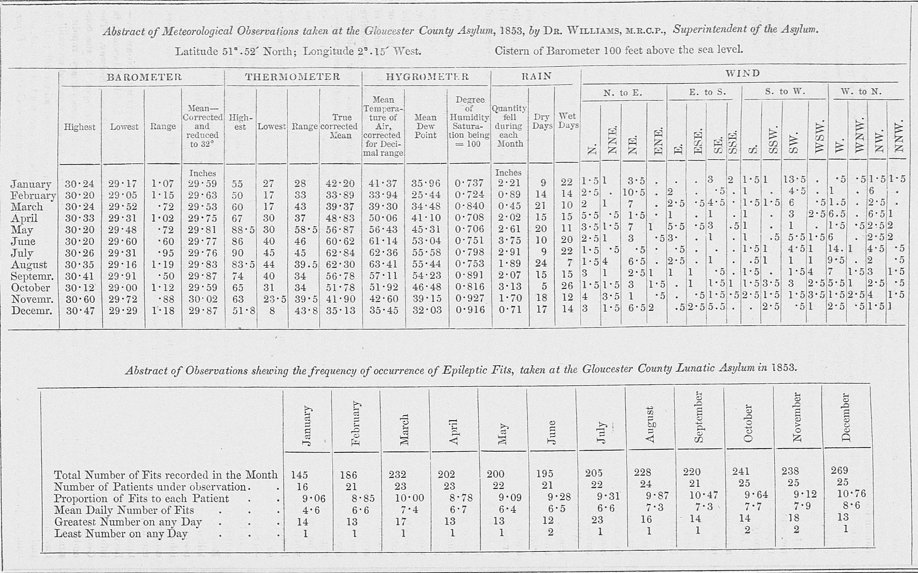

10/1/15 Is epilepsy affected by the weather?

The superintendent of Gloucester County Asylum tabulated information on his epileptic patients in 1853 to see if any connection could be made.

For the latest thinking on the subject go to http://www.epilepsy.com/node/998644

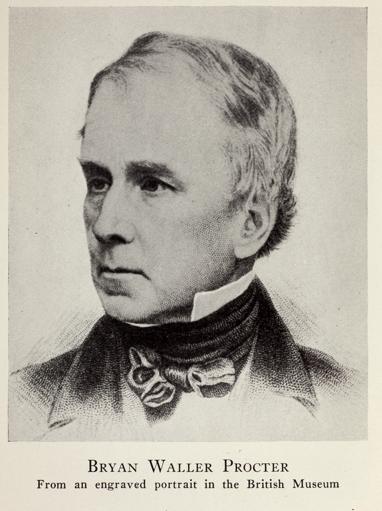

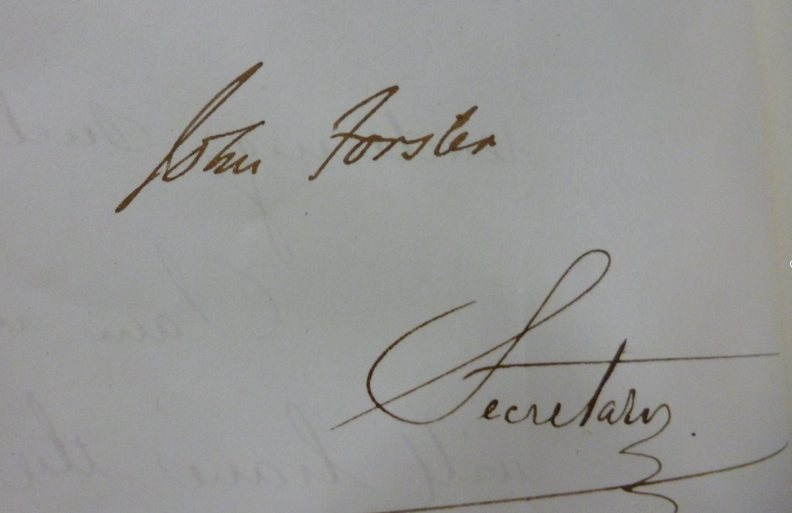

18/12/14 Confessions of a Lunacy Commissioner,1861: ‘What humbugs we all are’

It was a sad fact that some families would place a relative in a lunatic asylum and then neglect to visit him/her regularly; in some cases, contact ceased altogether as the years passed. I found this paragraph in a letter by Lunacy Commissioner Bryan Waller Procter in the Forster Collection housed at the V&A. Lunacy Commissioner (and Charles Dickens’ best friend) John Forster bequeathed his library and papers to the Museum, hence some interesting information on 19th-century mental healthcare is to be found in what might seem at first sight to be an unlikely place.

No matter how I peered, and held the paper up to the light, I couldn’t see through the thick black ink that obliterated the names of some patients in the run of Procter-Forster correspondence.

In a letter dated 3 September 1861, Procter (to whom, by the way, Wilkie Collins dedicated The Woman in White) tells colleague Forster:

‘I have several times, if you remember, said that they ought to go and see

poor _________ more frequently, but people are ashamed of their mad

relative, and leave them to the care of chance. You know of course in what

condition [Lunacy Commissioners] Wilkes and Lutwidge found _________’s brother. Your acquaintance ________ never going to see his daughter inflamed my indignation. What

humbugs we all are.’

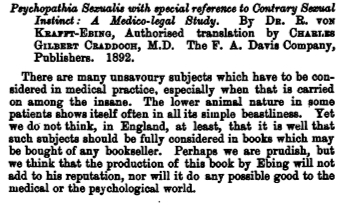

13/11/14 ‘Perhaps we are prudish...’

When an English-language translation of Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis arrived at the offices of The Journal of Mental Science for review, in 1893, the good gentlemen doctors were horrified (For more shock at ‘foul beastliness’, see post below at 1/7/14.)

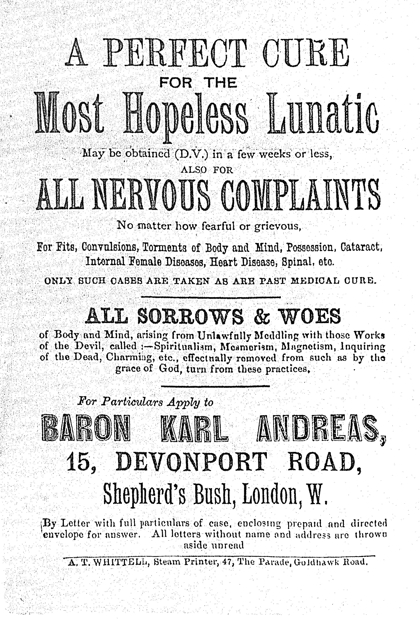

But they overcame their horror (slightly) and went on to run this review, by ‘E. R’, in the January 1894 edition.

2/10/14 Advertising for a patient (184 years ago)

Adverts such as these were controversial as it was not easy to keep tabs on, and inspect the conditions of, ‘single-patient’ lunatics, boarded in domestic premises. The Commissioners in Lunacy were keen to try to stamp out this type of canvassing, believing that either close family or a recognised institution should be the sole providers of care for the psychologically troubled.

This ad appeared in the York Herald of 2 October 1830.

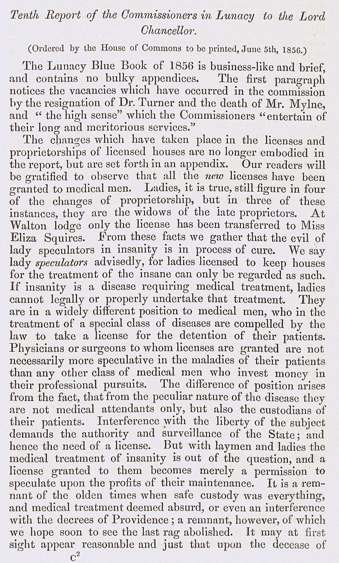

23/8/14 No ladies, please

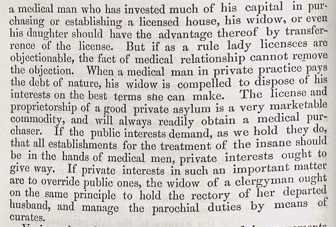

In their efforts to establish themselves as professionals, doctors of psychological medicine (they weren’t ‘psychiatrists’ until late in the 19th century) became more and more insistent that anyone without qualifications should be pushed out of mental health care. By the 1850s, women who superintended private asylums were to find themselves increasingly excluded from being licensed to do so. This is the logic: women were forbidden to study for medical qualifications, therefore no woman was a doctor, and since only doctors should run asylums, no women could be asylum superintendents.

The fact was, though, that many recoveries from mental illness happened either all by themselves without treatment; or came about as a result of being in a space where the patient was listened to and treated kindly – this was the famous ‘moral treatment’ system, which was as successfully undertaken by lay people as by medical men.

Thus the crackdown on women asylum licence-holders is likely to have seen off some much-needed helpers in the struggle to get people well again.

This is how the Journal of Mental Science reported on the changing licensing culture.

19/8/14 Going Off-Topic. . .

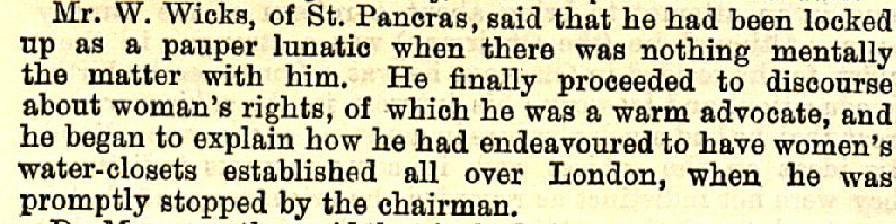

The Lunacy Law Reform Association meeting of 20 May 1874, in Gower Street, Bloomsbury, gets hijacked by a rather unsavoury subject:

17/8/14 The Patent Epileptic Bonnet

Concerned that people with epilepsy may damage their heads while fitting, one enterprising asylum worker patented a reinforced hat (which could be worn by both male and female patients). This sketch of the bonnet was circulated in the medical press of 1856.

1/8/14 Grace Poole advertises. . .

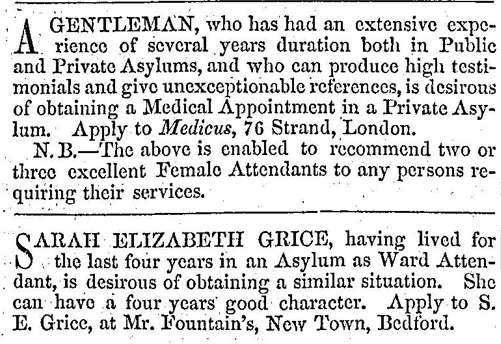

These two adverts on the back page of The Asylum Journal of Mental Science, July 1854, show a female lunatics’ attendant advertising for a position (bottom), and a male attendant adding that he knows of some good women for such a job. This type of notice may be how many home-based patients had keepers hired to look after them, à la Grace Poole in Jane Eyre.

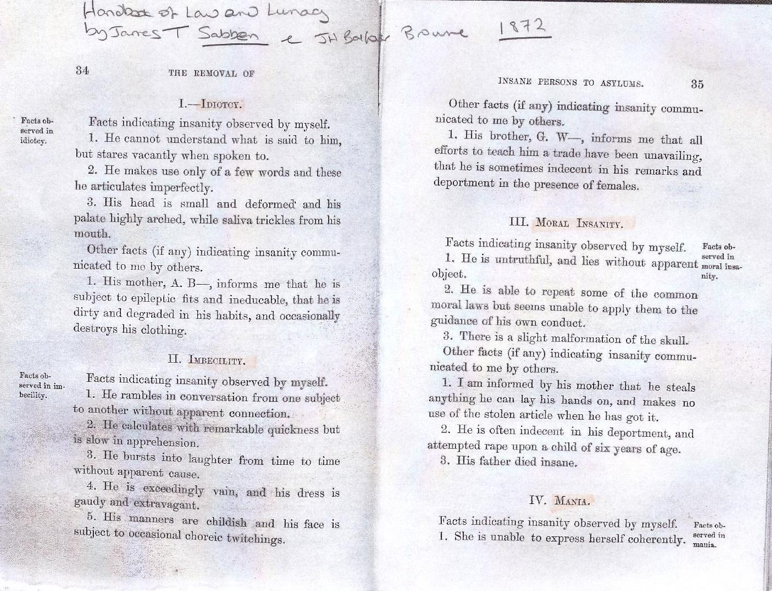

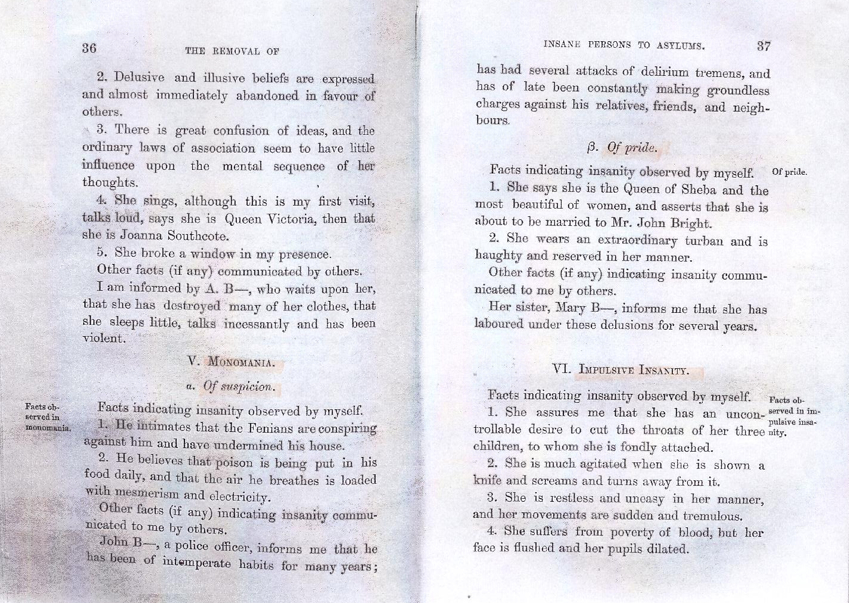

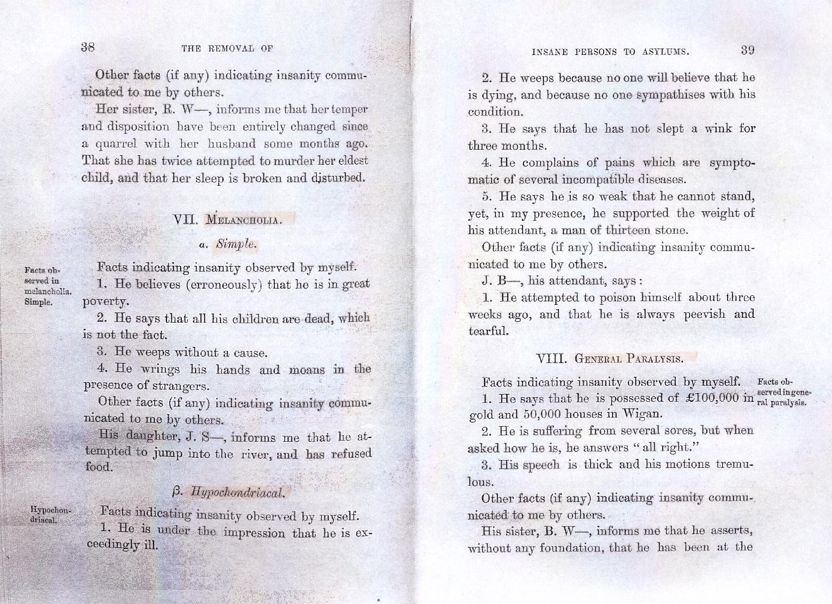

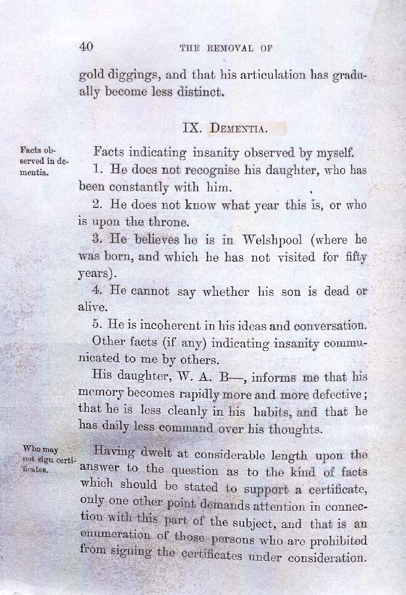

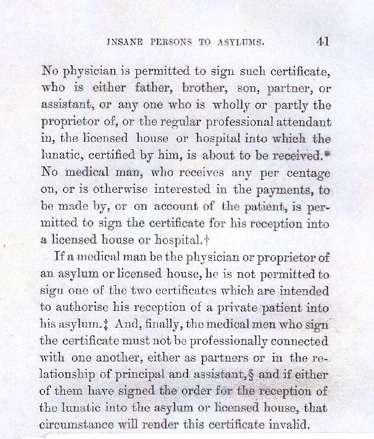

13/7/14 How to identify certain types of ‘lunatic’ – advice from 1872

There were many guidebooks and manuals of insanity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a competitive, potentially lucrative field, in which the mind doctors could put into print their theories and guidance based on their own practice. This 1872 forerunner to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) bases its categories on the personal observations of the two doctors. It is not particularly unusual for its time in England, though ‘monomania’ was on its way out as a diagnosis and ‘hysteria’ and ‘nervous’ conditions don’t feature here as largely as in other works.

1/7/14 Moral Perversion in Edwardian England – a doctor writes. . .

Charles Mercier (1851-1919) wrote his Text-Book on Insanity in 1902; it’s more straight-laced than most, and the following section should be read in your best Mr Cholmondley-Warner voice. (In the final paragraph, Mercier is unable to deal with the love that dared not speak its name – just cannot even countenance its existence.)

‘MORAL PERVERSION’

‘The fabric of morality rests upon a single foundation, viz., the ability to forgo a pleasure or incur a pain, now, upon the instant, in order that by our present self-denial we may secure benefit hereafter. Lack of this ability is evinced in vice, by which is meant immediate indulgence at the cost of disproportionate detriment hereafter. When vice is pushed to excess, it becomes insanity; and there are certain forms of insanity that are characterised, if not entirely, yet mainly and most conspicuously, by the excess of vice as here defined. Every form of self-indulgence, when it entails no subsequent detriment, either to the actor or to others, is right and proper and moral.

‘Only when it involves subsequent detriment to the actor is it vicious, and the degree of vice is marked, not only by the magnitude of the difference between the present pleasure and the future pain, but also by the certainty with which the pain is incurred, and by its imminence at the time the pleasure is indulged in; and when, in any of these respects, the degree of vice becomes extreme, it amounts to insanity. The thief who knows that his theft will never be discovered is not vicious in the sense in which "vice" is used here. If his booty is of great value and he knows that his punishment will be light and will not involve its restitution, he is still not vicious, for the benefit that he gets outweighs the pain that he incurs. If he incurs a heavy penalty, but there is little chance of his conviction, and of the penalty being inflicted, still he is not vicious; and if the penalty is both heavy and certain, but will be long delayed, then whatever the turpitude of his act, it is but little vicious in this sense of the word "vice".

‘But if the opposite state of things obtains, then the vice becomes extreme, and extreme vice is insanity. The man who steals under the very eye of the owner of the property, with the policeman standing by; the boy who takes the tarts while the pastrycook stands over him with uplifted cane; the clerk who embezzles money the day before the audit, well knowing that his defalcation must be discovered on the morrow; the candidate for a place who goes drunk to his would-be employer; exhibit a degree of vice so great as to border upon insanity, and beyond such a degree as this the insanity becomes unquestionable.

‘There are persons who indulge in vices with such persistence, at the cost of punishment so heavy, so certain, and so prompt, who incur this punishment for the sake of pleasure so trifling and so transient, that they are by common consent considered insane, although they exhibit no other indication of insanity.

‘The following cases are illustrative of moral insanity: an Afghan who had been deprived first of his right hand and then of his left, struck off in punishment for theft, seized with his stumps, and made off with, an earthenware pot of very trifling value, and did this under the very eyes of the police, well knowing that he would probably be hanged next morning, as in fact he was. A lad at college, the son of well-to-do parents, who kept him well supplied with clothes and made him an ample allowance, stole a suit of clothes and a pair of boots from a fellow student. He was seen to come away from his fellow student’s room with the clothes under his arm, but though he lied elaborately when taxed with the theft, he made no effort to conceal the stolen things, but left them lying about his room. He was expelled and sent home, and a few days afterwards he went to his father’s bedroom, packed up his father’s shirts, brushes, razors, etc., in a gladstone bag, and sold the lot to a man in the street for five shillings. A man of good social position and respectable ability, the colonel commanding a crack regiment, frequented low pot-houses, where he boozed with private soldiers of the lowest class, gave away his watch and chain and jewellery, and became filthy in person and swarming with vermin. A private soldier, on being reprimanded on parade by a commissioned officer for some trifling untidiness, smacked this officer in the face, and even when in prison, could not be got to see the matter in any other light than that of a good joke.

‘These are cases of true "moral insanity," but what are we to say of the frequent cases in which women of ample means and good social position steal from drapers’ shops? A small proportion of these are no doubt cases of moral insanity, but the majority of them are ordinary thieves, who presume upon their social standing and respectability to avert suspicion in the first place, and in the second to carry them scatheless if they happen to be discovered. Such women are not usually discovered to be thieves until they have continued the practice for some time and become bold from immunity. They execute their thefts with cunning and elaborate precautions, and when discovered they plead "kleptomania," which, in such cases, means theft by the well-to-do.

‘The consideration of moral perversion would not be complete without mention of the subject of

perversion of the sexual instinct, about which such a redundant amount of literature has lately been

produced. There is no doubt that there are abnormal beings of both sexes whose sexual inclinations are towards members, not of the opposite, but of their own sex, and these inclinations they gratify by various disgusting quasi-sexual proceedings. The fact being recognised, all has been said that need be said.’

19/5/14 The Abode of Love

A couple of weeks ago I was in Somerset and made a long overdue field trip to the various sites where The Abode of Love religious cult were located, 1840s to 1960s.

In Chapter 4 of Inconvenient People I tell the story of how Louisa Nottidge’s mother had her kidnapped and certified into a lunatic asylum near Uxbridge, Middlesex, in 1847; she did this in order to protect Louisa, and her inheritance, from sinister Abode of Love founder Reverend Henry Prince. Louisa and four of her sisters had run away to the Abode of Love and signed over their considerable fortunes to Prince. In despair and panic, Mrs Nottidge misused the lunacy laws to ‘rescue’ Louisa from the Abode and from what was, in her view, an even worse fate than wrongful incarceration.

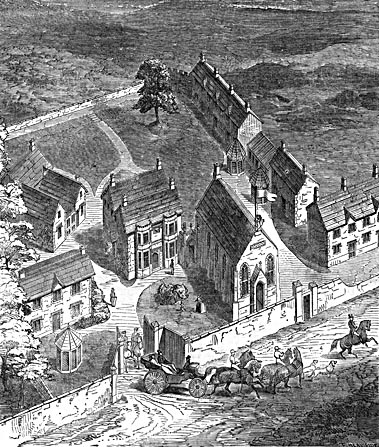

The Abode of Love (also known as The Agapemone) was a complex of buildings constructed in the early 1840s by Prince and his followers at the hamlet of Four Forks, Spaxton – four miles west of Bridgwater. The black and white drawing below from the Illustrated London News of 1851 shows Prince and some of the chosen few charging out of the main gates to parade their wealth around the narrow muddy lanes of this agricultural community.

The controversial cult survived until the early 1960s, and then the chapel was sold off and used as a film studio, where childhood favourites such as Camberwick Green were filmed. The ornate grounds of the Abode of Love have mostly been redeveloped for housing, as has the chapel. The infamous high wall (which signalled to the outside world that the Abode members wanted nothing to do with it) survives in stretches, though sections have been removed or reduced at the front of the chapel and the gatehouse (see below).

The surrounding landscape is extraordinarily beautiful: the cult owned a number of farms in the area (in order to overcome various trade boycotts put in place by hostile locals), and wandering through the woods at Aisholt, not far away, I located ‘Princeites Covert’.

In this small, steep-sided thicket (above) one of the several suicides by cult members took place. Many of the wealthy converts to the Abode of Love had had psychological problems before joining up, but the local coroner, the newspapers and the Home Office alleged that Prince’s behaviour had pushed some of them over the edge and into despair when he had questioned their loyalty, or indicated that they might not be among ‘the saved’.

Here’s a selection of the shots I took, from top to bottom, left to right:

Two shots of the chapel building of the Abode of Love;

the main mansion; one of the wooden gates into the original complex;

looking through the keyhole and into the gardens; the Four Forks signpost;

Louisa Nottidge’s grave at Spaxton parish church, just in front of its door, plus a long shot of Spaxton church – Louisa was freed from the asylum in 1849 and fled back to the Abode, dying there in 1858;

Charlynch parish church, where Prince’s sermons caused a riot among the local gentry and farmers.

Further info:

This video shows Dr Joshua John Schweiso being interviewed about the sect outside the Abode of Love in 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0g5sxiUgoo4.

Louisa’s gravestone is no longer easily legible but thankfully Dr Schweiso was able to locate it in the Spaxton graveyard.

Kate Barlow’s memoir The Abode of Love: The Remarkable Tale of Growing Up in a Religious Cult (2007) is a fantastic insight into the final years of the Abode of Love, from the point of view of a child

25/4/14 The tale of a table – one lunacy campaigner’s reward

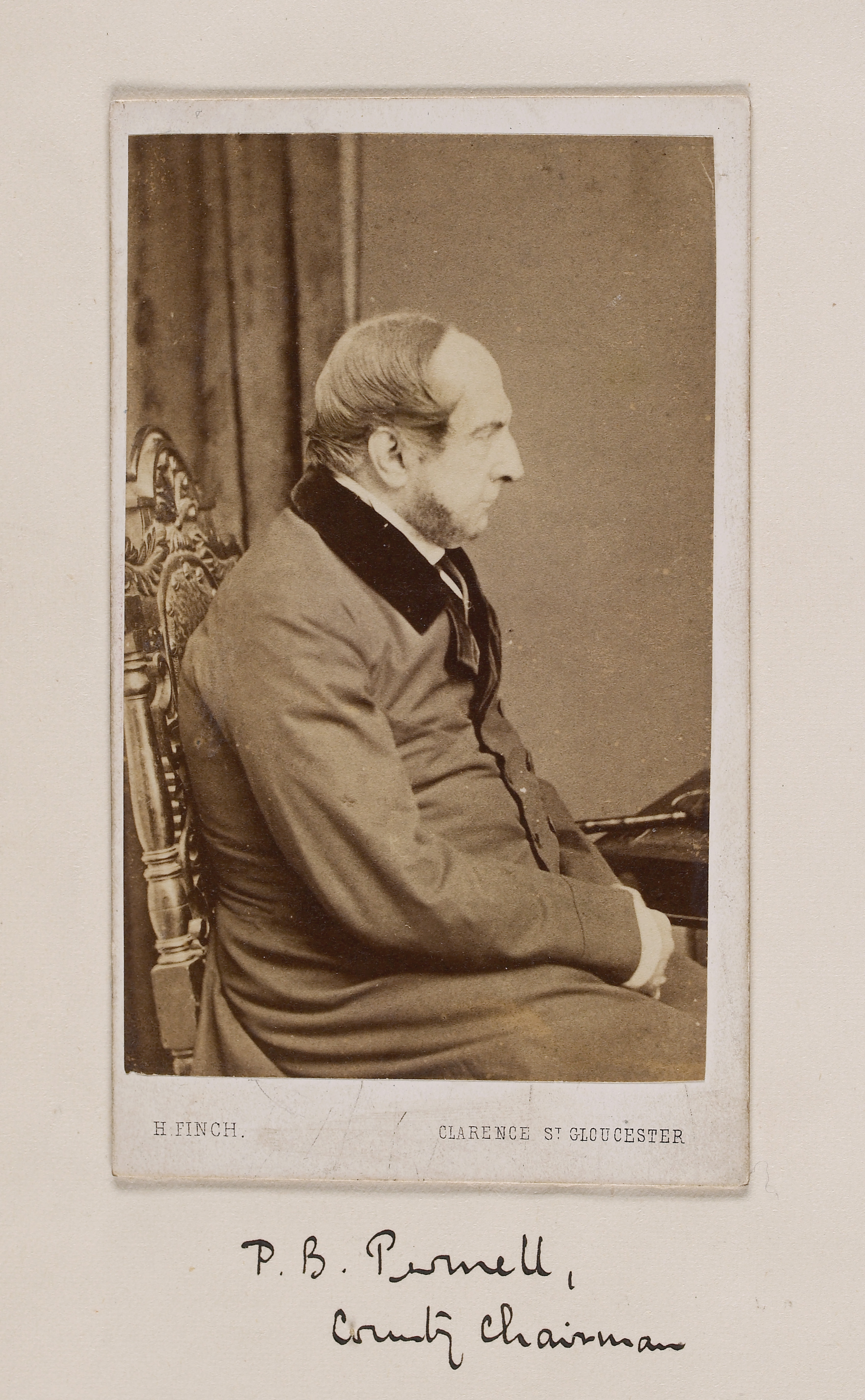

In the V&A museum is an opulent example of gratitude to someone who fought on behalf of sane patients who found themselves certified into insane asylums. In the late 1840s, Gloucestershire magistrate Purnell B. Purnell (pictured below) single-handedly instigated an investigation of that county’s asylums, with devastating

conclusions that grabbed national headlines in 1849.

Many

lunacy certificates were found to be invalid, some downright

untruthful, and some patients had clearly become sane during detention but had been

unable to get themselves discharged. One asylum was shut down and two proprietors had their licence renewals refused. Many sane people were released and their certification overturned.

Purnell hoped that his actions would demonstrate to the national inspectorate, the Commissioners in Lunacy, and to other English magistrates just how much could be achieved if the will-power was there.

He became a huge

local hero, and a subscription raised thousands of pounds, with which they bought him an ebony and rosewood table with silver inlay. It was

displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and remains the V&A’s grandest example of nineteenth-century presentation silver. The V&A is remarkably ungenerous in permitting imagery to be reproduced for free from its Picture Library, so you need to go here to see it:

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O84362/table-hancock-charles-frederick/

16/4/14 The old asylum wall at Ticehurst, Sussex

. . . and the gatepost, both taken by me during a long walk.

Below, Ticehurst in the 1830s. More images from the early days of the private hospital/refuge can be seen by visiting http://wellcomeimages.org/ and typing ‘Ticehurst’ into the search box.

11/4/14 How not to certify a lunatic: advice from a mad-doctor, in 1861

There was a lucrative trade in handbooks for doctors of psychological medicine – guides published on how to comply with the latest laws on the certification and detention of alleged lunatics.

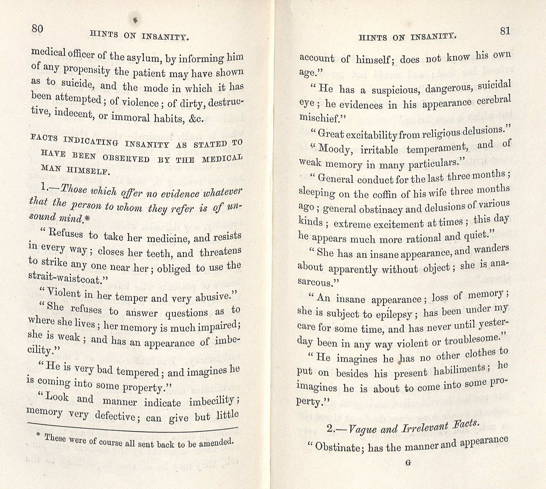

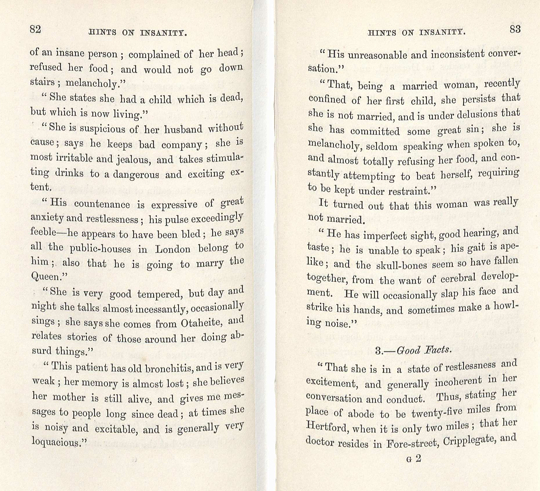

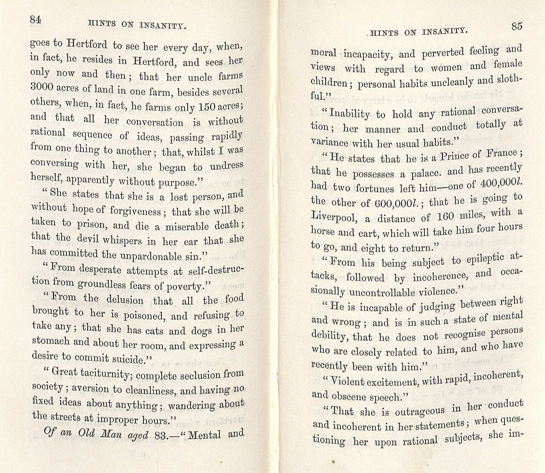

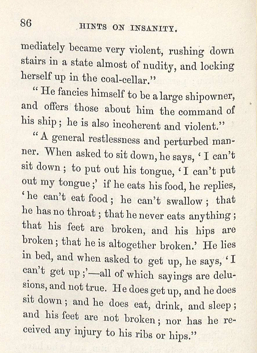

John Millar, superintendent of East London lunatic asylum Bethnal House, published his Hints on Insanity in 1861 (reprinted in 1877). It contained a chapter in which Millar reprinted as a warning the sorts of statements that would not pass muster with the Commissioners in Lunacy (who inspected all asylum admission documentation); and at the end of these Millar presented ‘Good Facts’, which would be considered valid.

19/3/14 Deprivation of liberty – back in the headlines

If only the issues I wrote about in Inconvenient People were purely historical. These past few days have put high on the news agenda the disregard of basic human rights shown towards those deemed to lack mental ‘capacity’.

This link takes you to the report of the Lords Committee, condemning the ‘Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards’ set up under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/lords-select/mental-capacity-act-2005/news/mca-press-release---13-march-2014/

This link reports on a legal judgment made today regarding the removal of liberty for physically disabled and learning disabled people

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-26643286

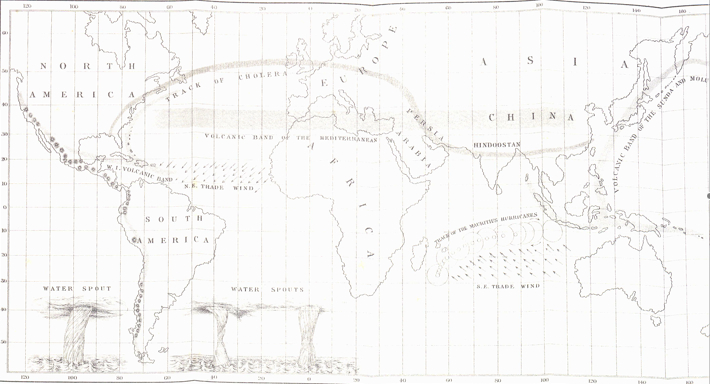

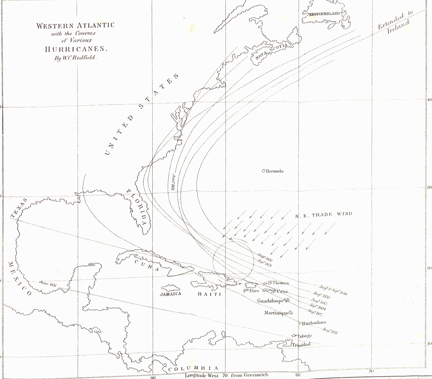

8/3/14 Hurricanes, volcanoes, trade winds – John Parkin’s theory of the pestilential planet

One of the most mysterious figures in Inconvenient People is Dr John Parkin. He first crops up in 1838 as a very early member of the patient advocacy body the Alleged Lunatics’ Friend Society; but eight years later he was jointly running (with his sister) a small private asylum, York House in Battersea. Mrs Catherine Cumming, the subject of Chapter 5 of my book, was very well treated by the Parkins, who were fond of her, and insisted that she spend time in their private quarters as she awaited the public hearing of her case.

It never came to light how Parkin moved so easily between anti-lunacy-law campaigning and being the proprietor of a profit-making mad-house. Parkin himself had had a serious breakdown and was placed in an asylum in the 1830s. He

did not allege that he had been wrongly incarcerated but was horrified at the conditions he had been kept in, and he joined the Alleged Lunatics’ Friends in order to raise standards for patients.

Parkin was additionally a respected epidemiologist, and his main hobby-horse was his belief that malaria, cholera and typhoid epidemics were caused by atmospheric violence brought about by hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and high winds rushing around the planet. I was reminded of Parkin’s hypothesis by this week’s news that British and American scientists believe that climate change has caused malaria to spread to previously unaffected high ground in both Colombia and Ethiopia, as such areas have become progressively warmer. (See further details of the findings at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/climate-change-is-increasing-the-risk-of-malaria-for-people-living-in-mountainous-regions-in-the-tropics-9174448.html )

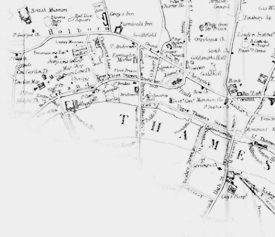

These two maps, and glowing reviews, come from the book that Parkin was working on when his mind collapsed, Epidemiology; or The Remote Cause of Epidemic Diseases in the Animal and in the Vegetable Creation, with the Cause of Hurricanes and Abnormal Atmospherical Vicissitudes.

25/2/14 Rascally goings-on in Birmingham

It was reasonably rare for an asylum proprietor to admit that there were corrupt practices in certifying patients. Perhaps it is because Dr Bodington had already won his spurs for his expertise in tuberculosis that the authorities sat up and took notice when he sent the following letter to the Home Office. George Bodington had taken over the running of the small, private asylum Driffold House (pic below) after achieving success in his TB specialism:

To the Right Hon Spencer Walpole, Her Majesty’s Secretary of State for the Home Department

22 Feb 1859

‘Sir,

‘Seeing that a Bill is submitted to Parliament to amend the law of lunacy, I beg permission to draw your attention to a point which possibly might otherwise escape it.

‘It is that certain proprietors of asylums have adopted the corrupt practice of obtaining patients for their establisments by bribes offered and paid to the family doctors who will send their lunatic patients to them. Advertisements have been inserted in the medical journals by such proprietors offering to pay 20 or 30 per cent out of the monies paid for the board and care of the patients to the medical men through whose interest they may obtain them.

‘I brought this question once before a meeting of the members of the Birmingham branch of the Medical Association and endeavoured to get a resolution adopted condemnatory of the aforesaid practice, but without success. . .

‘It seems the custom of openly advertising has ceased, but there is abundant reason to believe that the nefarious practice is still carried on secretly to a considerable extent. By it, the patient’s own funds are made available for compromising his interests in the establishment in which he may be confined, inasmuch as 20 or 30 per cent of such funds provided for his care and maintenance is given as a bribe to the friendly individual who secures his incarceration at a particular house [ie asylum].

‘It is scarcely possible to conceive anything of a more rascally character. It operates against the just liberality of the treatment due to the patient according to his means, and against his release when recovered, as the friendly individual aforesaid has an interest in advising his prolonged detention. Against the interests of honourable proprietors of asylums such arrangements are also most adverse. . .

‘In every point of view it is obviously a most corrupt practice and has a tendency to bias the judgment of medical men who yield to it when certifying as to the state of mind of patients. There is no more honourable profession than the medical, but many of its members are poor and ought not to be exposed to too great temptation on money matters...

‘I beg to remain

with great respect

Your Obd Srvt,

George Bodington MD

Proprietor of the Driffold Asylum,

Sutton Coldfield

nr Birmingham’

Office of the Commissioners in Lunacy, 18 Whitehall Place, SW,

5th March 1859

To H [Horatio] Waddington Esq, Home Office

‘Sir,

‘The Board [of the Commissioners] have had under consideration the letter of Dr Bodington calling the Secretary of State’s attention to the fact that corrupt agreements are entered into between the proprietors of lunatic asylums and the medical attendants of lunatics, and suggesting the insertion of a clause in the proposed new Lunacy Acts rendering such practices a misdemeanour.

‘I am now directed to request that you will have the goodness to inform. Mr [Home] Secretary Estcourt that this suggestion has the entire concurrence of this board. The Commissioners, believing in the existence of such practices, think it highly desirable that a clause should be inserted in the proposed Lunatics Care & Treatment Bill, rendering them penal, and, if required to do so by the Secretary of State, they are ready to prepare such a clause for insertion in the Bill.

‘I am, Sir,

Your obt Servt

John Forster’

[ie Charles Dickens’ best friend]

The clause was drafted, a Select Committee convened and legislation was eventually passed. Dr Bodington’s descendants have an excellent website that tells the story of their illustrious relative at http://www.boddington-family.org.uk/bodington/hist-bodington.gbmd.htm

13/2/14 A plot straight from Inconvenient People

This story has a mighty old-fashioned ring to it. Thankfully, justice has prevailed.

http://www.standard.co.uk/news/crime/banker-couple-waged-war-on-neighbour-over-12-inches-of-land-in-kent-village-9123330.html

4/1/14 The original British ‘Gaslight’

This afternoon I’ve just enjoyed the 1940 original film version of Gaslight at the British Film Institute on the South Bank – shown as part of the BFI’s ‘Gothic’ season. It’s not as glossy or smooth as the much better-known 1944 George Cukor version, starring Ingrid Bergman, Charles Boyer and a very young Angela Lansbury; but it’s nevertheless very good – with a fantastic set, ‘interesting’ B-movie faces, and a new take on the policeman hero – an overweight, ebullient older gent, who brings light relief to the very high tension.

One of the reviews of the British version, directed by Thorold Dickinson, pointed out the fantastic way that the interiors of the house (Number 12 of the fictional Pimlico Square) are co-conspirators in the plot to make our heroine lose her wits: ‘She is stifled under bric-a-brac,’ wrote the Eastern Daily Press reviewer on 14 June 1940. And it’s true – every shot in the movie has plenty for the eye to range over, in the over-stuffed Victorian room-sets and elaborate, constricting female clothing.

I got the idea for writing Inconvenient People while watching a stage performance of Patrick Hamilton’s original play Gaslight at the Old Vic Theatre in August 2007; in the darkened Dress Circle, it struck me – how often did that sort of lunacy conspiracy happen? How would the machinery of the law assist or hinder your plans if you wanted to put your highly strung but sane wife into an asylum? Did wives ever attempt to ‘gaslight’ their husbands?

Hamilton wrote his play in 1938 but set it in 1880. Watching the 1940 film today prompted me into some idle pondering on matters that can never be known – namely, to what extent, if any, was Hamilton thinking of some of the real-life malicious incarceration plots of the 19th century? In the movie versions, the heroine at one point calls and gesticulates from her bedroom window to somebody outside in the street who could help her, but then realises that if she shouts, her villainous husband will hear too. This was the dilemma of Rosalind Hammond, imprisoned in the family home, Laurel Cottage, Peckham Rye, in the early 1860s, by her husband, a doctor. Dr Hammond encouraged the female servants to make free use of Rosalind’s belongings, and he took one of them as his lover – the villainous husband and wicked maid are also lovers in Gaslight. Rosalind had tried repeatedly to signal from her barred window to passers-by but was badly beaten by her husband and the maids whenever she was caught doing so. (She eventually succeeded in raising the alarm from the window and the police came; in 1864, Dr Hammond was sentenced to 12 months’ hard labour, but the maids were scandalously acquitted for lack of evidence.)

Later, in 1869, vicar’s wife Louisa Lowe believed that her landlady and maids at her Exeter lodgings were in collusion with her husband, who wished to have her certified. Lowe wrote that the key to her rooms repeatedly went missing and then mysteriously turned up; that the bell by which she could summon the servants was muffled for no good reason. It was never established whether Lowe was correct about these phenomena, but they are very similar to the heroine’s ordeal in Gaslight – where objects are made to disappear and reappear and she is blamed for doing these things during an insane fugue-like state. (Lowe’s husband did get his wife certified into Brislington House Asylum, near Bristol, but she fought hard for her freedom and went on to found the campaign group the Lunacy Law Reform Association.)

Pimlico is an interesting choice for Hamilton to have selected for his setting: it had been shabby-genteel from its very creation – Belgravia’s poor neighbour. In the 19th century, newspaper reports featured a number of ‘single patients’ (lunatics kept as sole patients with a nurse or a doctor) disturbing residents in Pimlico with their cries at all hours of the day. For example, Dr Thomas Blanchard of 79 Warwick Square, was fined for failing to register his wealthy, and noisy, single patient Miss Kidston on the Commissioners in Lunacy’s ‘Private List’ of single patients.

It’s a long shot, of course, but it is tempting to wonder whether Hamilton was recalling some of these once- notorious old cases when he sat down to write in the late 1930s.

DVDs of both versions of Gaslight are available to buy, now that the BFI has restored the British version. It is a myth that Hollywood sought out and destroyed all copies of the British film, but it was deliberately marginalised in order to smooth the path of Cukor’s remake; and screenings were very rare before this restoration.

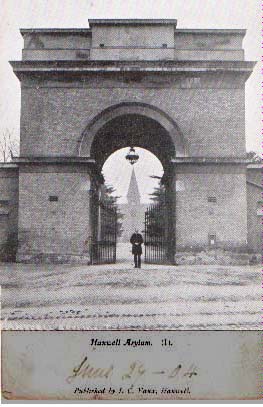

23/12/13 Hanwell Asylum at Christmas time

Among the improvements that Dr John Conolly (see various stories below) continued and developed at the Middlesex County Asylum at Hanwell were organised Christmas festivities for patients. These were gender-segregated, and pictured above is the males’ Twelfth Night Ball, 1848 (Illustrated London News, 15 January 1848). The female patients had a grand New Year’s Ball.

Music and dancing were hugely enjoyed by lunatic patients, whenever they were laid on; and some of the attendants were described as ‘tolerable’ players of flutes and fiddles.

The Twelfth Night Ball of 1848 took place in No 9 Ward and was attended by around 250 men; standing on the right in the picture are some of the various medical men, inspectors and magistrates who came along too.

For patients who preferred not to dance, games, including dominoes, bagatelle and draughts, could be played. At 8 o’clock, a roast beef dinner was served, and beer and tobacco handed round. The evening ended at 9.30pm with the singing of the National Anthem.

The figure furthest right of the dancing trio was ‘Poor Rayner’ – William Rayner, a comedian who used to play for many years the role of Harlequin at the Covent Garden Theatre. By 1848, Rayner had been an asylum patient for 16 years, having fallen into a deep depression following the death of his wife, who used to play Harlequin’s beloved Columbine in the same performances. At Hanwell, Rayner regularly acted his former role for the pleasure of his fellow patients.

For a darker exploration of an asylum Christmas Ball, read Charles Dickens’ article ‘A Curious Dance Round a Curious Tree’ here: http://www.lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~matsuoka/CD-Dance.html

12/11/13 Conolly Dell and Lawn House

This wonderful villa is Lawn House, in Hanwell, on the western edge of London. It was in use as a small private asylum in the mid- to late-19th century, with a maximum of six wealthy female patients in residence at any one time. Originally run by Dr John Conolly (who was also superintendent of the huge Middlesex County Asylum close by), Lawn House subsequently came under the management of Conolly’s son-in-law, psychiatrist-to-the-wealthy Henry Maudsley (see posts below dated 8/2/13 and 27/2/13).

Lawn House was (very sadly, in my view) pulled down in 1902, and today, only a forlorn hard-standing marks the spot (see my pic below, top pic).

However, the wider area is now known as Conolly Dell, to commemorate the doctor. It’s a lovely park, though it’s also true to say the lake could do with a dredge and clean-up, and the monument to Dr Conolly has seen better days.

Paul Lang has kindly supplied the two sepia vintage photos of Conolly Dell; plus the contemporary photo (bottom) from a series he has shot of the Dell and Hanwell.

Back in the 1870s Mrs Louisa Lowe was a patient at Lawn House, and in chapter 9 of Inconvenient People, I detail her hilarious complaints about its many deficiencies. So bad was the smell from the water, Lowe nicknamed the asylum Pond Hall, and claimed that the stench and the damp rendered the bedrooms at the front of the villa unusable. She said that the privies in the asylum (‘windowless and pestilential’) emptied straight into the pond, rendering the smells even more disgusting. And for this, Maudsley was charging the huge sum of £420 a year per lady. Lawn House, wrote Lowe, was ‘a whited sepulchre: bright, fair and surrounded by flowers – and foul within’.

Paul Lang is co-author (with Dr Jonathan Oates) of recently published Ealing Through Time (Amberley Publishing, £14.99). The Lawn House vintage picture is part of the wonderful collection at Ealing Local Studies Library http://www.ealing.gov.uk/info/200461/local_history_centre

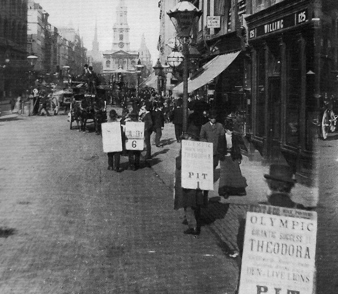

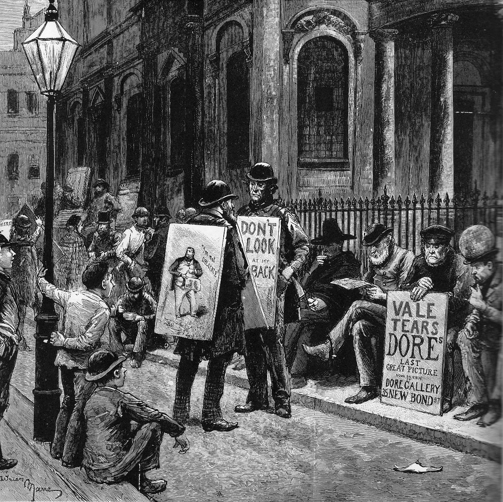

27/9/13 Sandwich Men: what was the filling?

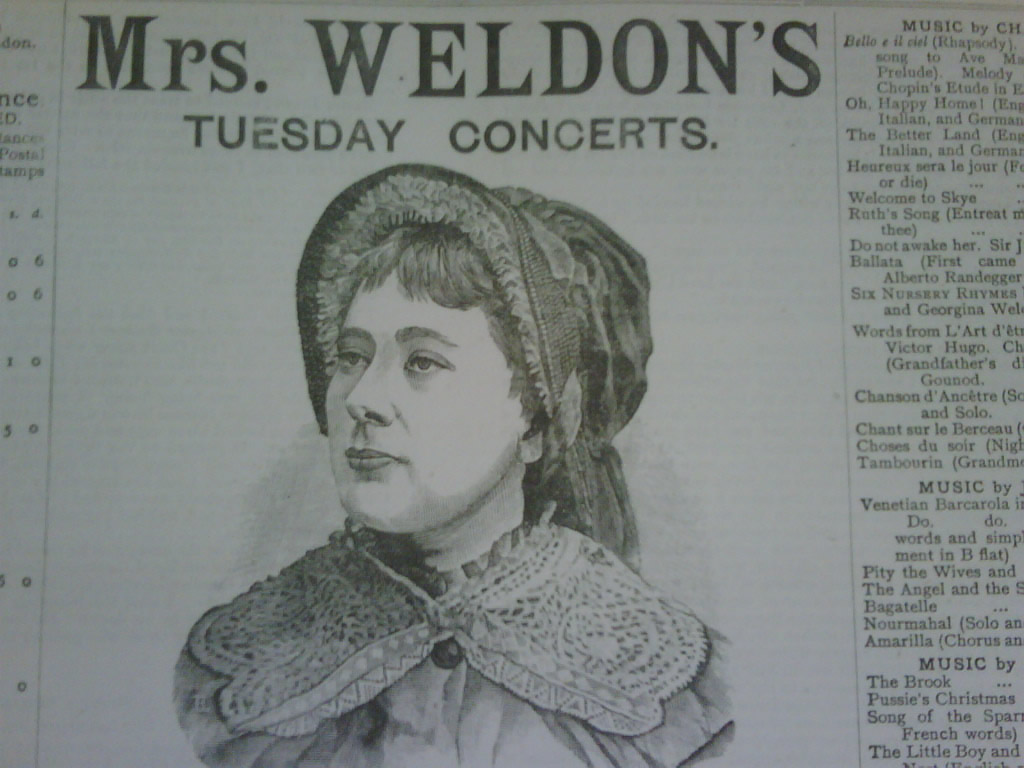

Mrs Georgina Weldon (1837-1914) took many different types of revenge on the men who had plotted to have her unjustifiably certified insane. One of her funniest coups was to hire sandwich-board men to parade up and down all day outside the West End home of Dr Lyttleton Stewart Forbes Winslow, lunacy specialist and private asylum proprietor. Emblazoned on their boards were the words ‘Body Snatcher‘. Much hilarity resulted. And then she sued him.

At 2s and 6d a day, sandwich men were a relatively expensive way to advertise, or to publicise your wrongs, as Mrs Weldon did. The men themselves didn’t see much of the money, though, as this 1872 interview with ‘an animated sandwich’ (as they were also known) reveals. The sandwich said:

‘You see as how sandwiches never can get on, ’cos we’re a broke-down lot. Why you should see us affor’ we starts with our boards, all a rubbin’ our rheumatisms or a coughin’, so as it is wonderful how we gets on. But lots of us is respectable, though we ain’t always honest, as we get into a public house instead of crawling, and there we enjoys our pipes and talks. Why, one on us is a queer old man what had a good business in the muffin line, and it’udd make you stare if you heard the poetry he makes up, and then you would laugh, and then your eyes would water like.

‘Well, today he brings in a new song all by hisself, and it all ends with what is called, “The man what walks in the gutters”. And it’s a correct account of how we are looked down on, and shows that none of our old pals will shake our paws, as it’s awkward like when your harms pop out of your side like serampores at the railway; and then it shows that it’s no good to police the men what gets drunk, and

fine ’em five shillings, the correct thing being to make ’em sandwiches for a week with ’vertisements about them teetotal meetings. And then

nobs would mayhaps have to do the boards, which would helewate the perfession, as all what they does helewates.’

Source: The Man With the Book; or, The Bible Among the People by John Matthias

Weylland, 1872.

Below: images of animated sandwiches in London in the 1870s.

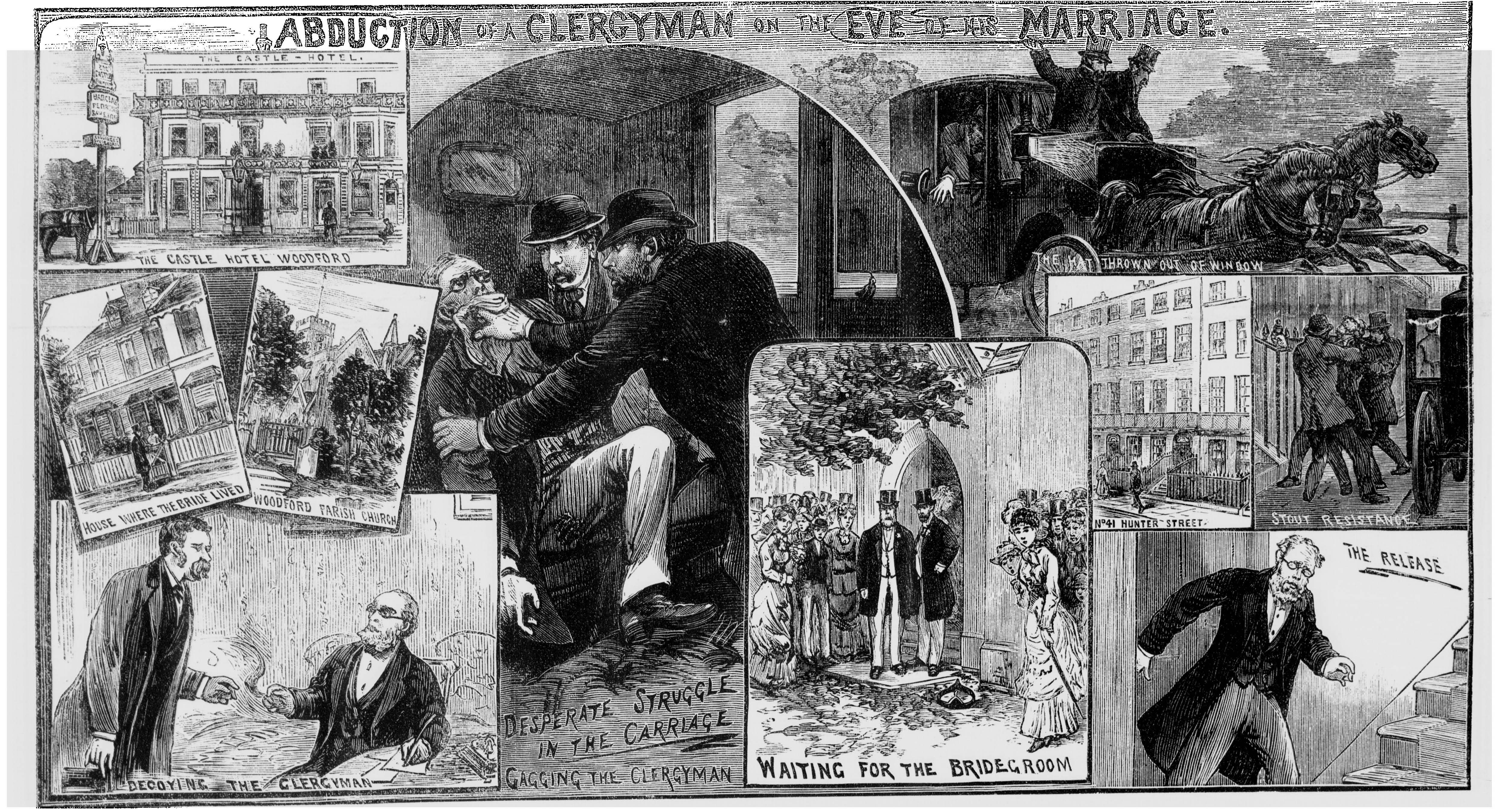

3/9/13 The adventures of Reverend Kennard

This is one of my favourite madhouse abduction stories –- partly because it has a swift and happy dénoument, but also because the victim is someone who we today might think is atypical. The plot was undertaken against an elderly, wealthy vicar – a figure of authority and great respectability; but in fact, such gents were disproportionately likely to be the target of such conspiracies, especially when they were so headstrong as to wish to marry, or to make/remake a will. At such moments, relatives could become rattled – suspecting that large inheritances were about to be diverted.

This is how the front page of the Illustrated Police News told the story of Reverend Kennard.

Reverend Robert Bruce Kennard, the sixty-year-old rector of Marnhull in Dorset, was a widower, with eight grown-up children. He had been intending to marry one Miss Pritchard, but she had fallen through the ice at Christmas 1879 while skating on the River Stour. He later fell in love with the German governess of a wealthy family, forty-year-old Miss Bade.

On 13 September 1881 the reverend arrived at the Castle Hotel in Woodford, in Essex, one day ahead of his marriage to Miss Bade. When three gentlemen turned up in a carriage at the hotel, they told him that they were there to take him to Woodford parish church to check the details of the next day’s ceremony; but after a short time in the carriage, he realised he was being driven into London instead. He called to the men, who told him to shut up if he valued his life. He shouted and threw his hat out of the carriage in order to alert passers-by but no one responded.

The carriage arrived at a lodging house at 41 Hunter Street, near King’s Cross, and Reverend Kennard was locked in a room, given a meal, and told that a doctor would come along the next morning to certify him insane.

The next day, the bride stood at the altar, the reception party was waiting in the Castle Hotel, but the vicar did not arrive. No one could understand the reliable old gent’s non-appearance. Miss Bade fainted in church with the shock of it all.

The conspirators should have checked the reverend’s pockets, for he had a great deal of cash on him; and the next morning, he offered a considerable sum to the man who had been sent to watch over him before the doctors were to arrive. The cash was accepted, and Reverend Kennard walked out of the front door, into a hansom cab, and then by Great Eastern Railway to Woodford.

The reunited couple walked up the aisle the next day, and went on to honeymoon at Windsor.

The likely perpetrator of the plot was kept under surveillance by the police; but they were unable to take action unless the vicar was willing to come back to London to make a formal charge against this person. This, Kennard was unwilling to do – perhaps preferring to let the fact that the attempt had been so widely publicised was punishment enough, and that a new attempt would be highly unlikely. Or perhaps it was Christian charity.

28/8/13 Broadmoor’s 150th anniversary

I’ve posted a piece about how Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum functioned in its first few years, on the Psychology Today website:

http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/lunacy-and-mad-doctors/201308/gaslight-stories-the-early-days-broadmoor

20/8/13 The 2013 Select Committee on mental health

Many of the problems I highlight in Inconvenient People are still with us, albeit in altered shape. Last week saw the publication of the report of the Select Committee on how the UK’s 2007 Mental Health Act is working. Of particular note, regarding liberty and wrongful incarceration, is the Committee’s finding that the ‘Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards’ are not working well. These safeguards were set up in 2007 to protect those who lack mental capacity – most commonly those with Alzheimer’s or with severe learning difficulties. Some 7,000 patients have been found to have been deprived of their liberty by institutions or care workers without the proper procedures having been followed; two-thirds of requests to restrict a person’s liberty were not even reported to the Care Quality Commission, as required by law.

Also causing worry is the rise in the unecessary sectioning of the mentally ill, as the quickest way of accessing any kind of care whatsoever, due to a shortage of psychiatric beds. Sometimes doctors were having to take this very drastic step as the only option for obtaining treatment for a patient. Committee chair Stephen Dorrell said, ‘It is never acceptable for patients to be subjected to compulsory detention unless it is clinically necessary.’

A digest of the Select Committee report can be read here:

http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/health-committee/news/13-08-14-mha2007cs/

The full report is also available to read online.

7/8/13 The princess and the cherry juice

Many mad doctors of the nineteenth century wrote of lunatics who were able to suppress their delusional notions, often for quite long spells, and claimed that this was why many of them appeared, to non-medical folks, to be sane. The doctors even devised a name for this condition: insania occulta. Sceptics replied that this caught patients in a double bind: if they expressed delusions, they were declared mad; if they failed to express delusions, they were deemed to be mad but cunning.

One of the anecdotes that did the rounds in legal and medical circles for many years harked back to the prosecution in the eighteenth century of Dr John Monro of Royal Bethlehem Hospital by one Mr Wood; Monro had certified Wood insane and had him incarcerated. Mr Wood, a merchant of the City of London, sued the doctor for false imprisonment. For hours in the courtroom, Wood spoke in a calm and rational way, recalling precise details of events and conversations. It looked as though Monro was about to lose the case, as Wood appeared to be a sane man.

At this point, one of Monro’s legal team whispered into the ear of the barrister questioning Wood, advising the barrister to ask Wood a very specific question – namely, ‘What became of the princess with whom you were corresponding in cherry juice?’ Instantly, according to one who was there in court, ‘Wood showed in a moment what he was. He assured the court that because he was at that time, as everybody knew, imprisoned in a high tower, and being debarred the use of ink, he had no other means of correspondence but by writing his letters in cherry juice, and throwing them into the river which surrounded the tower, where the princess received them in a boat.

This onlooker continued: ‘There existed, of course, no tower, no imprisonment, no writing in cherry juice, no boat, but the whole inveterate phantom of a morbid imagination.’

Dr Monro was immediately acquitted, and the Wood case was repeated often as a warning against the highly plausible lunatics, who needed to be questioned on specific matters in order for a torrent of delusionality to begin to flow.

Dr John Charles Bucknill wrote in 1857 of patients of his who for hours at a time would appear fully sane, except when certain subjects were touched upon. One barrister under Bucknill’s care never said anything irrational, yet would sit up all night writing reams of letters boasting of his (non-existent) huge wealth, his yacht voyages to the ends of the earth, and his marriage to several servant girls.

Bucknill said that night-time often called forth whole worlds of delusional fantasy in men who by day seemed fully sane: ‘I have for several years had under my care a respectable tradesman, whose conduct and conversation during the day exhibit scarcely a trace of mental disease. He is industrious, sensible and kind-hearted, and it is strange that his nights of suffering have left no painful impression on his pleasing features. At night he sees spectres of demons and spirits, at which he raves aloud and prays with energetic fervour.’

Dr Lyttleton Stewart Forbes Winslow had, in the 1870s, at his West London asylum, Sussex House, a ‘homicidal maniac’, who had made two attempts upon his wife’s life. The man used abusive language about her constantly while at Sussex House at night-time; but during the day he was able to suppress his delusions and appeared to be a contrite and loving husband. Dr Winslow also had captive a man who seemed sane by day but who spent his nights writing graphic and obscene letters to his family, his acquaintances and to high-profile strangers (all were intercepted and destroyed by Winslow).

It would be interesting to know how much, if anything, Robert Louis Stevenson knew of such cases of daytime sanity and night-time raving. Works of genius such as The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde cannot, and should not, be pinned down to a single inspiration, but it is tempting to think that this sort of discussion in psychological-medical publications may have played some small role in the creative spark.

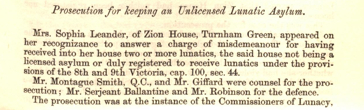

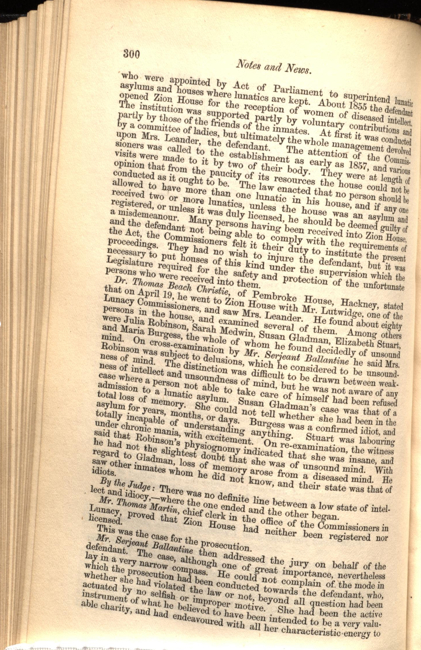

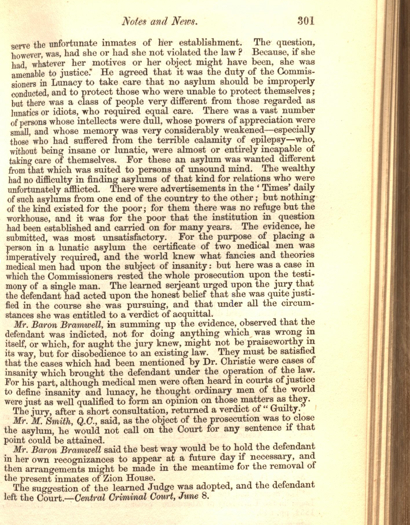

14/7/2013 Illegal Asylums

After 1845, anyone who set themselves up to care for more than one lunatic on their premises had to obtain a licence to run an asylum from the Commissioners in Lunacy. The Commissioners mounted prosecutions of those who failed to do so, and the report below, from the Journal of Mental Science in 1864, tells the story of one of the largest ‘illegal’ asylums that they shut down – Zion House in Turnham Green, west London.

Critics of the Commissioners in Lunacy claimed that the inspectorate only ever went after the minnows – that the illustrious mad-doctors with the expensive asylums were treated more leniently than private individuals such as Mrs Leander; she, it is pretty clear, I think, was trying to operate a safe-house for women who were in mental distress, though perhaps not clinically insane. It seems that many of Mrs Leander’s ladies had what we today term ‘learning disabilities’ (the report uses the contemporary term ‘idiocy’).

Campaigners against the lunacy laws believed that female proprietors in particular were being driven out of business by the patriarchal Commissioners in Lunacy, who would not accept that women might be better cared for in female-run establishments. One Miss Elliott had had her eight-patient asylum in Chelsea, Elm Lodge, shut down in 1845, against the wishes of the inmates’ families. She was eventually re-licensed but for the short period of six months, whereafter she had to reapply at six-monthly intervals.

For her part, Mrs Leander is reported in another account of her trial to have rejected any interventions on her behalf by any male: ‘It is a ladies’ concern and we will not allow men to interfere,’ she told the court. . .

1/7/2013 The CQC under fire

I’ve just posted my latest blog on the Psychology Today website, in which I look at the similarities between the current plight of the UK’s Care Quality Commission and the battles faced by the Victorian Commissioners in Lunacy.

You can read it at: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/lunacy-and-mad-doctors/201306/gaslight-stories-mistreatment-patients-then-and-now

27/6/2013 The Death of Uncle Skeffington: Guest Blog by Jeremy Moody

Lewis Carroll’s favourite uncle, Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge (‘Uncle Skeffington’), paid the ultimate price in his job as Commissioner in Lunacy, on a visit to Fisherton House Asylum, near Salisbury in Wiltshire. Former asylum gardener Jeremy Moody tells the story. He has also provided the wonderful images at the bottom of this post.

‘Fisherton House Asylum, which became known as The Old Manor Hospital, is an establishment with a fascinating history. My father Jack Moody had gained employment there as a sign writer in 1962 and it was my pleasure to listen to the many wonderful stories that some of the older patients had related to him – some of them had been there since the 1930s.

‘I followed Dad and became head gardener at the asylum/hospital in 1988, a position that gave me immense satisfaction because the grounds had been landscaped to a very high standard – indeed, they had remained virtually the same since Victorian days.

‘Some years after I had been working at the establishment, a book was produced featuring old photographs of the hospital that had been kept in a large plastic bag. I was asked to help find additional material and spent many a happy hour researching newspapers, books and archives. I learnt how the underground tunnels, running from one end of the hospital to the other, had been put in place to segregate the female patients (who walked through the grounds) from the male patients (who walked through the underground tunnel).

Probably one of the most intriguing stories that my researches uncovered was that of a patient named William McKave.

‘By 1873, McKave had been confined in Fisherton House for more than twenty years, prior to which he had been incarcerated at Bedford Asylum for more than seven years. McKave was said to be haunted by a woman named Mary Taylor, with whom he had once cohabited – he was under the delusion that she was still visiting him at the asylum. These delusions were the only reason McKave was being detained and he was not considered to be a dangerous patient.

‘Notwithstanding this, the Salisbury Journal reported that McKave “it appeared, was a troublesome patient”, their rather intolerant reasoning being that “he had repeatedly applied for liberty, and had stated that it was his intention to do something of a nature that would, as he was tired of Salisbury, ensure his being sent to some other place of confinement”.

‘William Corbin Finch, the proprietor of Fisherton House, said “I have heard him repeatedly ask the Commissioners [in Lunacy] for his liberty, and heard him express a wish to be removed to Broadmoor, the government asylum for criminal patients. He was not considered to be a dangerous lunatic, although he was in the habit of threatening.”

‘McKave had made numerous appeals to Finch and, more importantly, to the inspectors of the Lunacy Commission. The Commission, created in 1845 by the Lunatics Act, consisted of six professional inspectors (three physicians and three lawyers) whose full-time job was to make unannounced inspections of the 177 lunatic asylums in England and Wales. As well as passing judgment on these establishments, the inspectors also had the authority to discharge patients who had been inappropriately admitted.

‘On 21 May 1873 two Commissioners, Dr James Wilkes and Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, arrived to inspect Fisherton House. McKave’s frustration and anger at constantly having his appeals rejected had now reached boiling point. When the inspectors arrived at Ward 17, where McKave was incarcerated, he pretended to be asleep until such time as they moved to leave, when he leapt forward and struck Lutwidge in the temple. McKave had been concealing a nail in his right hand, the point of which penetrated Lutwidge’s skull, such was the force used by McKave.

‘Lutwidge was helped to the house of William Corbin Finch, where he was attended by a Salisbury doctor, William Martin Coates. He was then transferred to The White Hart Hotel, Salisbury. Lewis Carroll/Charles Dodgson [pictured below], upon being telegraphed, rushed to Salisbury accompanied by the eminent London surgeon Sir James Paget of St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Lutwidge rallied a little and Carroll returned to London; but unfortunately Lutwidge’s condition rapidly deteriorated and he died on 28 May. Lewis Carroll recorded in his diary his “dear Uncle’s death”.

‘In court, McKave pleaded not guilty to murder, but said he did not wish to deny he had dealt the ultimately fatal blow. After hearing all the evidence the judge addressed the jury: “I do not know what inference you may draw from the evidence, but surely you are not to condemn a man to death for an act committed in a lunatic asylum, seeing that he had been an inmate of it for twenty-one years, and an inmate also of another lunatic asylum for six or seven years previously, and seeing that he has suffered during all that time under chronic mania, and that a gentleman who appears as a witness for the prosecution, and who has been familiar with the prisoner’s conduct, his habits, and with the sad disease under which he labours, tells you his opinion is that the prisoner is not responsible for his actions? I think, whatever further evidence may be forthcoming, it will be for you to consider whether you could pronounce a verdict which would consign him to the gallows after the evidence which has been laid before you. If, on the evidence, you think he is not responsible for his actions, and that he was in an unsound state of mind on the 21st of May, it will be your duty to return a verdict of not guilty, in which case he will be kept in confinement during Her Majesty’s pleasure. If you desire, however, that the case should go further, do not let anything that has fallen from me prevent you from hearing additional evidence.”

‘After a brief deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty on the grounds of insanity.

‘Lewis Carroll and his uncle were extremely close friends, despite a thirty-year age difference. They shared many interests, including the study of insanity, and Carroll is said to have accompanied his uncle on visits to asylums. Many scholars have commented on the prominent theme of madness in Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking-Glass, both written in the decade before Lutwidge’s death.

‘Little more than a year after the death of his uncle, in July 1874, Carroll began writing what many consider to be his most famous poem, “The Hunting of the Snark”. Ever since the poem’s first publication, it has intrigued and baffled scholars. Many believe it is an expression of his grief at the loss of his uncle, closest friend and intellectual companion – a poem about the Lunacy Commission and the death of Lutwidge following his visit to Fisherton House Asylum.

© Words, and pictures below, Jeremy Moody, www.timezonepublishing.com

Fisherton House Asylum in the 1840s; and below, boarded-up.

Bottom: the tunnels that run beneath the site.

19/5/2013 Off the Rails

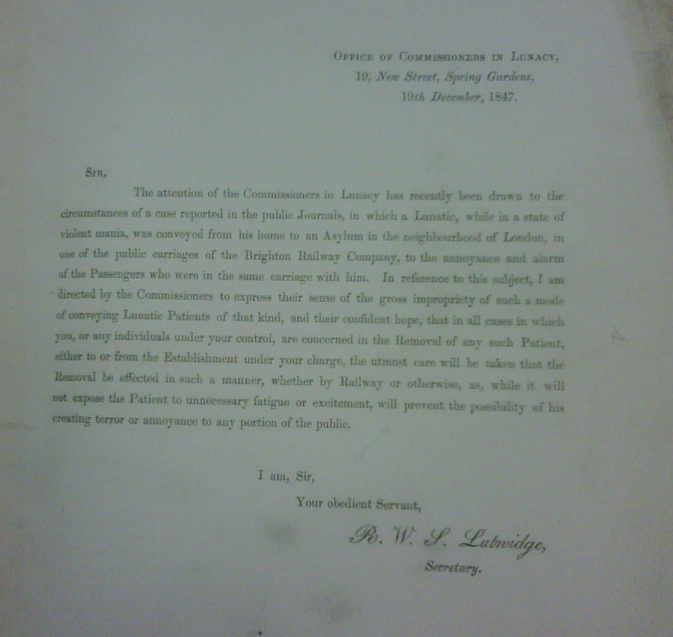

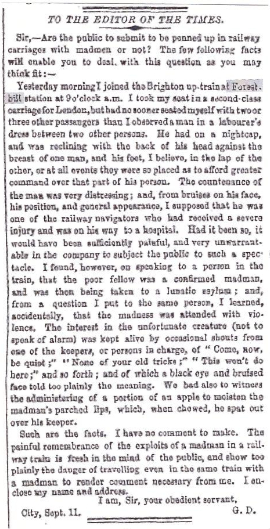

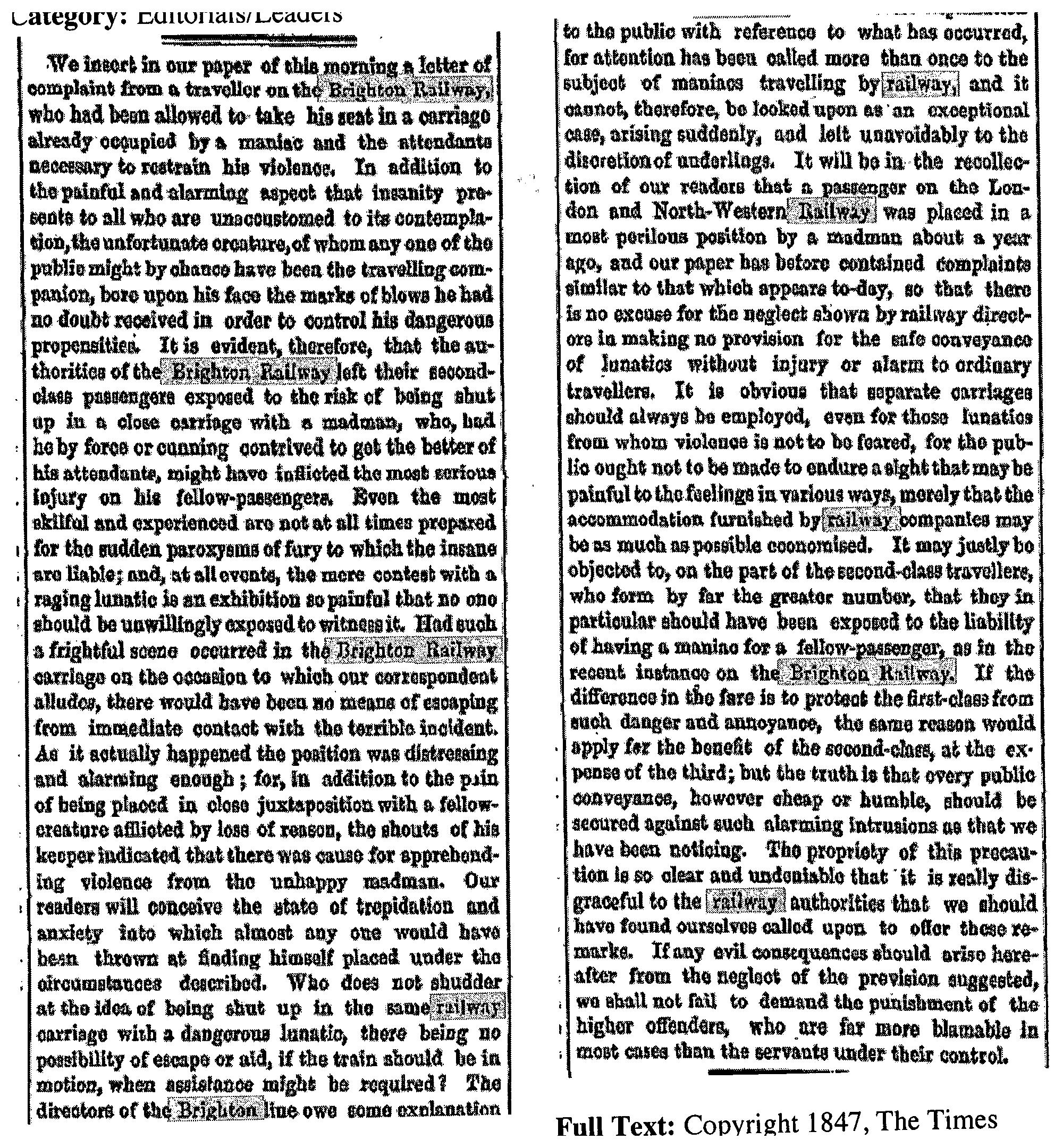

Lewis Carroll’s Uncle Skeffington was the man who drafted the landmark lunacy legislation of 1845, which remained in place until the 1890 Lunacy Act. RWS Lutwidge was a lawyer and had been appointed secretary to the Commissioners in Lunacy inspectorate, later becoming a full Commissioner.

This memo of 1847 was his response to the problems that could arise when somebody mentally ill was being transported to an institution on public transport. An alarming incident in the September, on the Brighton to London railway line (see the newspaper cuttings beneath the memo), had prompted this circular, which was sent to all the nation’s asylum superintendents to warn them that such removals must never alarm the public or distress the patient.

15/5/2013 The Shepherd’s Bush solution

It would be intriguing to know exactly how Baron Karl Andreas treated those who responded to his newspaper and magazine advertisements. Quack medicine was huge business in the 19th century, and ‘nervous’ diseases were a highly lucrative market.

20/4/2013 Syphilis again . . .

A huge number of male lunatics were admitted to asylums suffering from a condition that was understood in the 19th century as ‘general paralysis of the insan’ (GPI). A very interesting piece on this condition, written by one Dr E Salomon, appeared in the Asylum Journal in 1862, in which the word ‘syphilis’ is not mentioned but a link with a venereal infection is clearly being made; this link would not be fully confirmed by anatomy and microscopic investigation for many years.

As in the 27/2/13 posting below, about Henry Maudsley, Dr Salomon pointed out how symptoms of GPI are also the symptoms of other medical conditions. Salomon wrote of the majority of GPI sufferers being in ‘full manhood’ and rarely younger than 30; they have lived ‘too fast’ and have ‘fallen victim to enervating excesses, particularly those of a sexual character...France is the peculiar focus of the disease... Paris is the headquarters.’

The disease, stated Salomon, runs from some months to three years, but never beyond five. The article insisted on four stages of GPI: mental alteration; mental alienation; dementia; amentia – ie total paralysis of the mind.

Symptoms were both physical and mental, he continued: firstly, an astounded, vacant look; an inability to perform the simplest mental operations; confusion of ideas and sense of environment; ‘this devastated intelligence is maintained throughout the disease, regardless of other mental changes’; a deteriorating temper; uncharacteristically impetuous acts – ‘extravagant and dissolute, dishonest and debauched’.

In terms of movement, the first stage included spasms of the face; disturbed speech, including stuttering and stopping mid-sentence; vertigo; a staggering gait with legs spread wide.

In the second stage, the insanity seen in GPI cases differed from non-GPI insanity, wrote Salomon. In this second stage, grandiosity was ever-increasing and was a progressive delirium not found in other grandiose insanity cases. There was also persistent raving, without lucid intervals.

Salomon thought that GPI insanity was most often confused with alcoholism, muscular atrophy and apoplexy.

‘There is also seen in GPI maniacal exaltation and grandeur; melancholia; loquacity without delusion; false ideas and hallucinations.’ Those who lived on to the fourth stage, which was rare, would find their sight and hearing annihilated, and the patient would be bed-bound: ‘The wreck of the unhappy man lies dull and immoveable as a sack of flesh... Soon, however, death puts a long wished-for close to this extreme limit of human misery, as the patient is only a burden, a mass of foetid lumber here upon earth.’

25/3/2013 The Museum of St Bernard’s