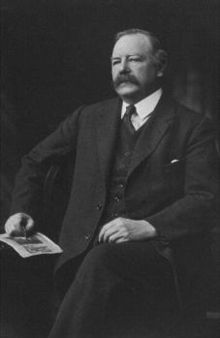

Arthur Pillans Laurie (1861-1949) was a chemist who pioneered the dating of paintings by analysis of their pigment composition. He would go on to become principal of Heriot-Watt College in Edinburgh. As a young man, Laurie had wanted to learn about the lives of the poor, and like many university undergraduates and graduates, he went to spend time in an East End “mission” in the late 1880s – he chose Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel.

In his 1934 memoir Pictures and Politics: A Book of Reminiscences, he recalled his East End experiences, not least, the evening he believed had come face to face with Jack the Ripper. Remembering his time at Toynbee Hall, Laurie wrote: “The West End was gradually becoming aware that a vast industrial population lived beyond Aldgate Pump, with a dead level of poverty governed by a few obscure and corrupt vestries, and with no municipal life. . .

“There was an atmosphere about Toynbee Hall which irritated us. . . We were supposed to be noble young men engaged in trying to do good to the poor. We did not feel noble and we had no desire to do good to anybody, and were quite incapable of doing so. We wished a closer contact with the people and lives of East London. . . Toynbee Hall was very much in the limelight then, and irritating flocks of gaily arrayed young men and women used to descend upon us from the West End. Slumming became a fashionable amusement. After a good dinner, a crowd of men and women would be personally conducted through the worst slums known, prying into people’s homes and behaving in an intolerable manner. We wanted to get away from all that.

“I was teaching at the People’s Palace. . . [Hubert Llewellyn] Smith was working for [Charles] Booth, collecting material for London Labour and the London Poor, [Arthur] Rogers was on the local vestry. . . We had dug ourselves in. We liked East London. The Mile End Road on a Saturday night is the most picturesque street in London. I passed the happiest years of my life in Stepney. East London is real. It is in touch with the facts of life. George Lansbury [Labour MP and leader of the Opposition] is to be respected because he lives in East London, his native city.

“In the days I speak of, Whitechapel was inhabited by two types of residents in the main – foreign Jews mostly from Poland, and a shifty, semi-criminal population, in the dark and narrow closes and courts behind Toynbee Hall. The two populations were divided by Commercial Street. For neither of these populations had Toynbee Hall any message.

“[Further east there were] no public institutions, no educational facilities beyond the elementary school, no public opinion, and governed by a few corrupt and incompetent vestries. The remarkable thing is that so vast an area, with no government, remained so peaceful and law-abiding. This area was inhabited by a large artisan and labouring population. Innumerable industries were and are carried on. The ignorance of this vast city on the part of the rest of London was remarkable. They penetrated as far as Whitechapel with its picturesque squalor and degraded population, and imagined that that was East London. The right place for Toynbee Hall was Poplar, or Mile End.

“On one side of Commercial Street there was a rabbit warren of slums, hardly lighted at all at night, and consisting of narrow streets, with passages and courts opening off which had no lighting, making easy the ghastly murders of Jack the Ripper. Here and there the wide-open doors showed the kitchen and living room of a common lodging house heated by a huge fire where a bloater could be cooked, and with a collection of ruffians round the door whose faces would have made the fortune of a film of the underworld. The respectable inhabitants of Whitechapel complained that this slum district was getting very riotous at night and the police were getting very slack, and suggested a watch committee and nightly patrols between eleven and one.’

“This was undertaken by the Toynbee Hall men, who were organised to patrol the district, and to note events without interfering. Often they patrolled alone, and without even the protection of a walking stick.

“The semi-criminal has no more courage than a rabbit, and behaved accordingly. No Toynbee man was ever molested, and I have always been completely sceptical of the stories of places in London which were not safe to enter at night. I have picked out of the gutter an occasional respectable grocer from the provinces in nothing but shirt and trousers, and in a state of stupor, which suggested drugging, but either drink or love had led to his undoing.

“Hideous shrieks of ‘police!’ and ‘murder!’ used occasionally to arise, but we learnt to treat them with indifference. I never found that there was any reason for complaining of the police. In those dark and primitive regions they resembled the cadi in the Arabian Nights, kept order, administered a rough justice and were appealed to on all sorts of occasions. A conversation between a thief and a policeman in the midnight hours is very amusing – the thief all oily obsequiousness, the policeman grimly sarcastic.

“Obtaining a lodging at the police-station was not an unknown device. I watched an old lady one night dancing a wild fandango in the middle of the road, and shrieking out a torrent of obscene abuse at three policemen, watching her and muttering curses. They knew her game. She had no money and was determined to compel them to arrest her. She was disturbing the whole neighbourhood, and sooner or later they would have to run her in.

“It was during the winter of our patrol that the horrible Jack the Ripper murders began in Whitechapel. . . A cry for help would receive no attention when it was so common. It became our rule to strike a match and light up dark courts and passages and open stairways, with a shudder at what we might see. Occasionally we unearthed a detective standing in a corner, silently waiting. Whitechapel was swarming with detectives hoping to trap the murderer. The strange thing was that a new murder was known in Whitechapel before the police heard of it. One murder was committed in a room. I was told of it at 1am, while patrolling the slums. The police did not know of it it till seven.

“I believe I saw Jack the Ripper one night while patrolling the slums, but that, as Kipling says, ‘is another story’.”

Which – can you believe it? – Laurie never goes on to tell (unless it lies somewhere in his private papers, held by Heriot-Watt University). Surely that’s one of the biggest let-down moments in any memoir . . .

**************

A strange and unpleasant change in Laurie took place in the later 1930s. He had started as a socialist – even helping to organise strikes; became a Liberal – failing to be elected as an MP in 1929; and in 1939 wrote a celebratory book about German National Socialism – The Case for Germany. Its dedication reads: “It is with admiration and gratitude for the great work he has done for the German people that I dedicate this book to the Führer.”

In this book, Laurie writes admiringly of the peasant stock of both Germany and of his native Scotland, with their long-held folk traditions and their sensible suspicion of city folk and urban sophistication. Young Hitler had become a labourer, wrote Laurie, choosing to live penuriously in a cellar with fellow workers, and refusing to join a union. Laurie said that he would not, could not, defend the Führer’s anti-Semitic legislation, but wished to point out that every Continental European nation had undergone its pogroms, so why single out Nazi Germany?

In the year in which the Second World War would begin, Laurie wrote confidently: “Those who say that Hitler is out for the conquest of other peoples show a complete misconception of his beliefs.” Lots of people were getting it wrong about Hitler, of course, but 1939 is pretty close to the wire – pretty close to an accusation of wilful ignorance. (Let’s hope Laurie’s pigment analysis was more successful than his geo-political insights – otherwise there may be some iffy Rembrandts knocking around.)

It’s always interesting to read the thoughts of someone who had lived so long and believed so many different things – especially when the writing lacks self-consciousness and courts neither applause nor brickbats. Back in 1934, before his conversion, Laurie had written:

“Looking back on the years from 1880 to 1914 one sees that a great advance was made in the social conditions of the people. A sturdy Labour group in the House of Commons gingered up the Government of the country, and the medical profession seriously attacked the problems of the general health of the masses of the people, and succeeded in carrying much useful legislation. Radical leaders like Chamberlain in his younger days, and like Lloyd George, carried reform after reform. Municipalities became active, and at last London was given a central government and the London County Council turned a powerful searchlight on many dark places. Politically this advance in education and social welfare is almost entirely due to the Liberal Party, but behind it were armies of keen and enthusiastic workers, guided by the teaching of the medical profession, who had devoted themselves to these problems.

“Asquith’s great Factory Act brought laundries under the scope of protective legislation. Middle-class suffragettes had opposed this, saying that it interfered with women’s freedom. I still remember the rage which filled us. How I longed to take those women and let them taste the blessings of freedom by a week’s work in a London laundry of those days.

“It is a foolish and wicked lie that no good can be done by Act of Parliament. When the common people have made up their minds in favour of a social reform, it is only by Act of Parliament that it can be carried out.”

Pictures and Politics: A Book of Reminiscences by Arthur Pillans Laurie, 1934; and The Case for Germany: A Study of Modern Germany, 1939