Yes, it’s a cliche, but fogs really did used to make London more mysterious and eerie – people even said so at the time. I came upon these two passages while researching The Italian Boy – they’re from 1826 and 1837 respectively.

Firstly, here’s Peter George Patmore, in The Mirror of the Months, writing about autumn and winter fogs:

“Now the atmosphere of London begins to thicken overhead, and assume its natural appearance – preparatory to its becoming, about Christmas time, that ‘palpable obscure’, which is one of its proudest boasts. . . As an affair of mere breath, there is something tangible in a London Fog. . . In a well-mixed Metropolitan Fog there is something substantial, and satisfying. You can feel what you breathe, and see it too. It is like breathing water, as we may fancy the fishes to do. And then the taste of it, when dashed with a due seasoning of sea-coal smoke, is far from insipid. It is also meat and drink at the same time; something between egg-flip and omelette soufflée, but much more digestible than either. Not that I would recommend it medicinally, especially to persons of queasy stomachs, delicate nerves, and afflicted with bile. But for persons of a good robust habit of body . . . there is nothing better in its way.”

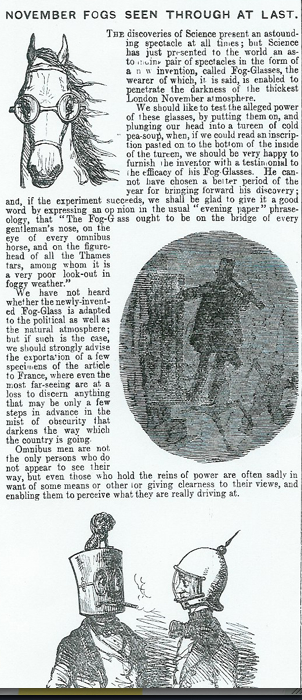

In the 19th century, Punch magazine found fog an ongoing source of visual wisecracks. Below left: a little urchin leaps out of the fog and scares an old lady. Below right: is it time to re-introduce the 18th-century “link man” to London, to guide people on their way home? Bottom: the various uses to which patented anti-fog glass could be put.

My second foggy (and smoky) extract is from Dr John Hogg’s fantastic compendium of facts plus eccentric opinion – London As It Is (worth checking out in its entirety):

“The cross on St Paul’s Cathedral is nearly on a level with Hampstead Heath, and the clearness of the atmosphere at that height may be easily seen in London by observing that, although the town may be enveloped in fog and smoke, the gilt ball and cross on the cathedral are sparkling in the sunshine. The same contrast is vexatiously experienced if a person mount the dome of the building for the purpose of seeing the metropolis at one view; on reaching the elevated station, he sees the country for many miles around, but if he looks for London, he finds himself literally in nubibus, a firmament being between him and it…

“London is frequently enveloped in a mist, or fog, of greater density than is observable in any other part of the kingdom, more particularly in winter. . . The dry fog, so frequently observed in the months of November and December in London, seems to be composed chiefly of smoke, which, from its great weight, is unable to rise from the earth, when the surrounding atmosphere, as indicated by the fall of the barometer, becomes specifically light. The colour of it corresponds with that of smoke, and it generally possesses a sooty, suffocating odour. Its sudden invasion of, and as sudden departure from, different parts of the town, and its not being seen often after midnight, or at any other time when fires are not generally burning, would lead one to conclude that exhalations from the earth have very little to do with this species of fog. It is of a bottle-green colour, but if the barometer rise, it will either totally disappear, or change into a white mist.

“It is sometimes so dense as to prevent objects being discerned even at the distance of a few yards, and, in consequence, many accidents occur in the streets, from the carriages and other vehicles coming into contact with each other. This state of atmosphere is considered peculiar, and has the appellation of ‘the London fog’. It causes such darkness that lights are indispensable for the transaction of business. It sensibly affects the organs of respiration, so much so, indeed, that persons having delicate lungs frequently experience a feeling of suffocation. Powerful as is the gas flame in the lamps, the light is not discernible many yards from the lamp-post. . .

“The principal cause of complaint against gas works, soap-, sugar- and candle manufactories, breweries, distilleries and foundries is the frequent vomiting forth of dense volumes of black, suffocating smoke, filling all the adjoining streets with stifling fumes and darkening the very atmosphere. The effluvia occasioned by the former of these works is well known as being injurious to health, and it is unfortunate for the inhabitants that establishments of this description are not kept at a proper distance from their habitation. The contamination of the atmosphere by repeated inhalations of nearly two millions of persons cannot easily be avoided, neither can the half a million of fires in private houses be suppresesd; but the wholesale poisoning of the air by these works might be prevented, without any public incovenience being occasioned. In a word, all public works should consume their own smoke, or be prohibited in the metropolis.

“Many persons think that the smoke is beneficial rather than prejudicial to health in London, on the idea, probably, that it covers all other offensive fumes and odours; this notion cannot be founded in truth; for even admitting that it conceals from the senses innumerable effluvia that would otherwise have caused disgust, it is in itself most prejudicial to animal, as well as to vegetable, life. It need only be remarked that smoky places are invariably the dirtiest and the most unhealthy, whence it is easy to discover the true bearing of the facts of the case… Moreover, smoke is prejudicial in another way: light is essential to vigorous health in both the animal and the vegetable economy, but the enlivening rays are effectually excluded in London, for days together, by the volumes of thick smoke which hang over the town.”