On re-reading Mrs Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Bronte (1857) recently, this passage jumped out at me:

“It was about this time that an event happened in the neighbourhood of Leeds, which excited a good deal of interest. A young lady, who held the situation of governess in a very respectable family, had been wooed and married by a gentleman, holding some subordinate position in the commercial firm to which the young lady’s employer belonged. A year after her marriage, during which time she had given birth to a child, it was discovered that he whom she called husband had another wife. Report now says that this first wife was deranged and that he had made this an excuse to himself for his subsequent marriage. But at any rate, the condition of the wife who was no wife (of the innocent mother of the illegitimate child) excited the deepest commiseration; and the case was spoken of far and wide… Some of [Bronte’s] school friends consider that [this] incident which she heard when at school at Miss Wooler’s was the germ of the story of Jane Eyre. But of this nothing can be known, except by conjecture…”

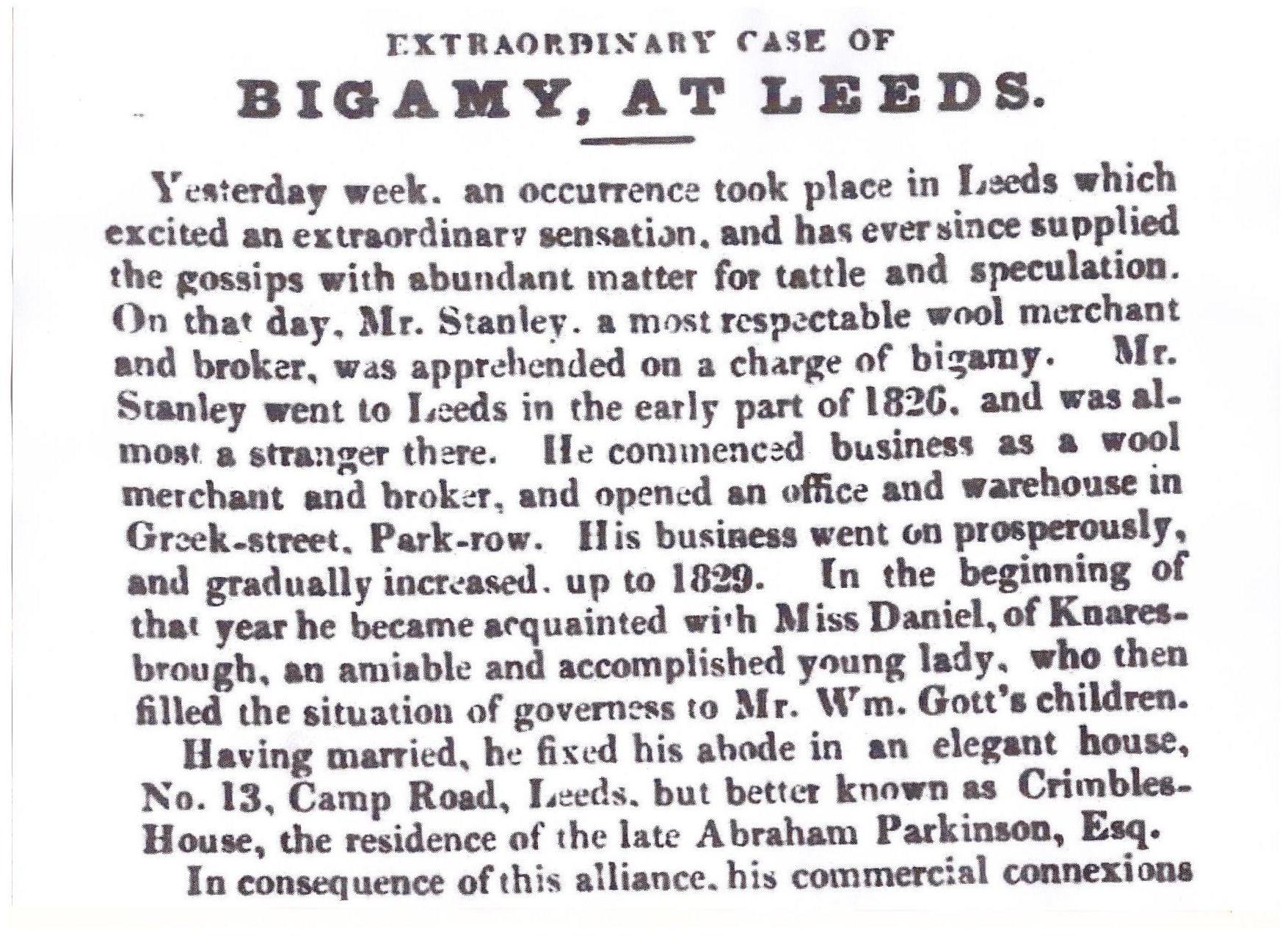

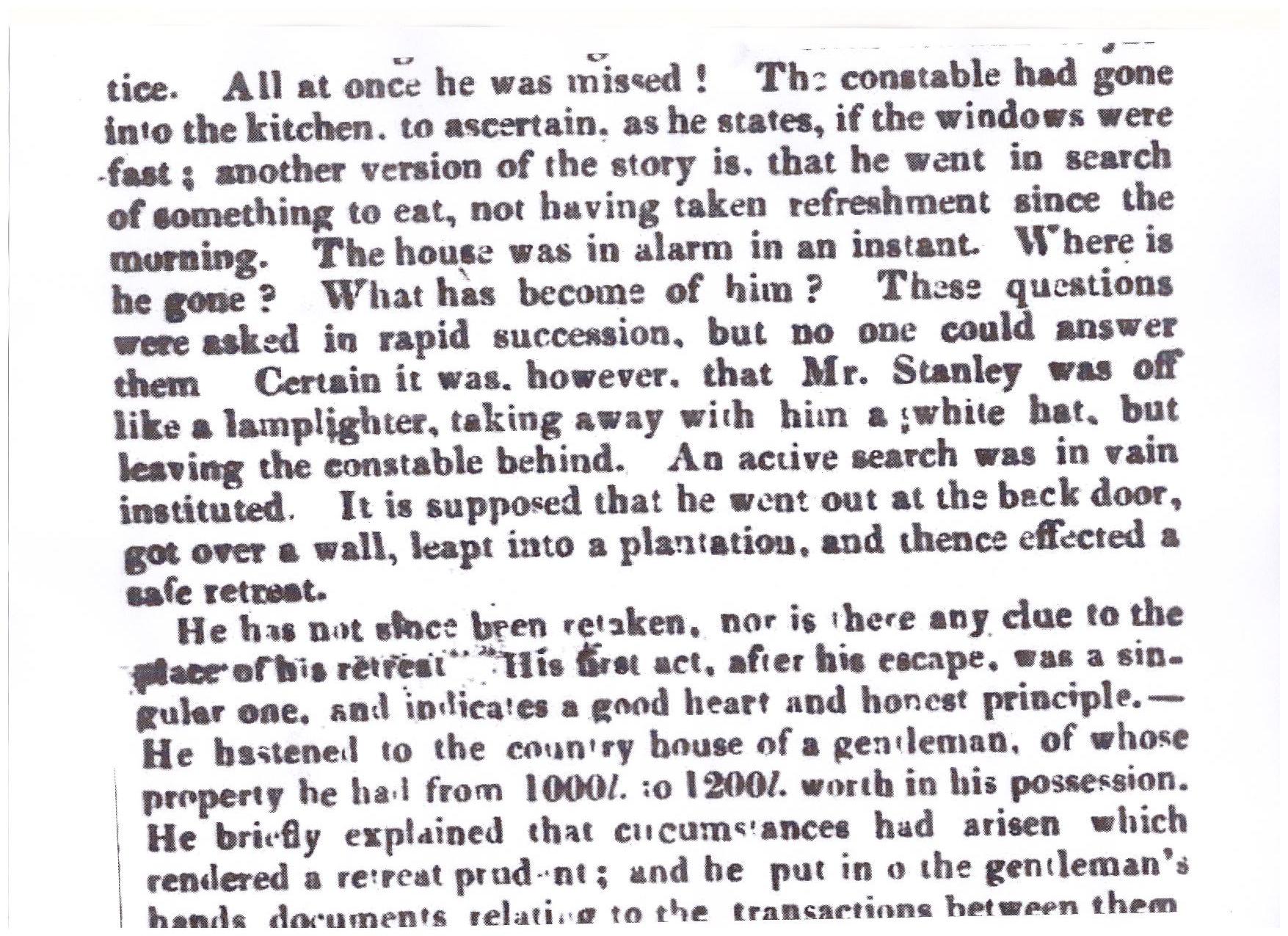

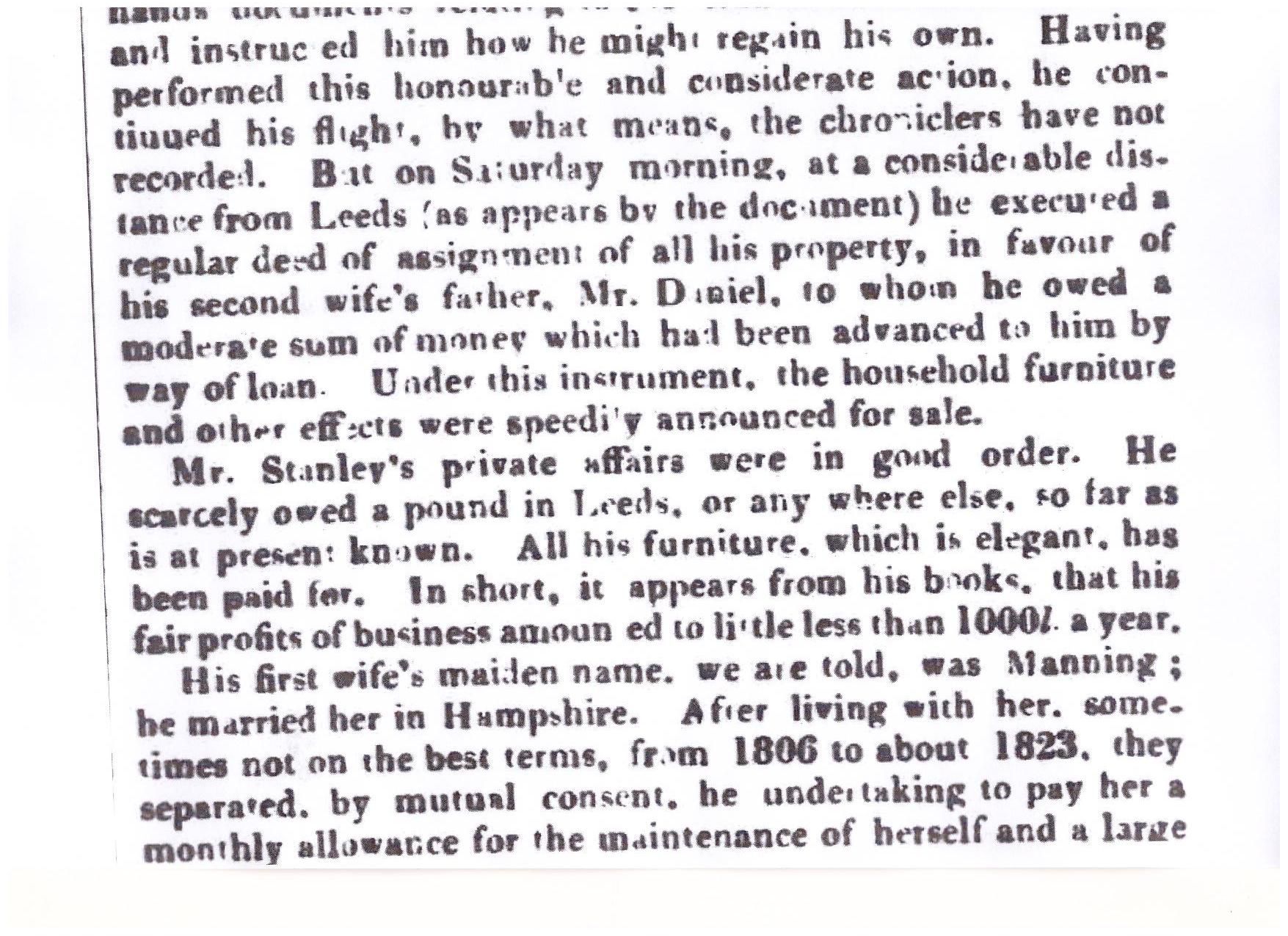

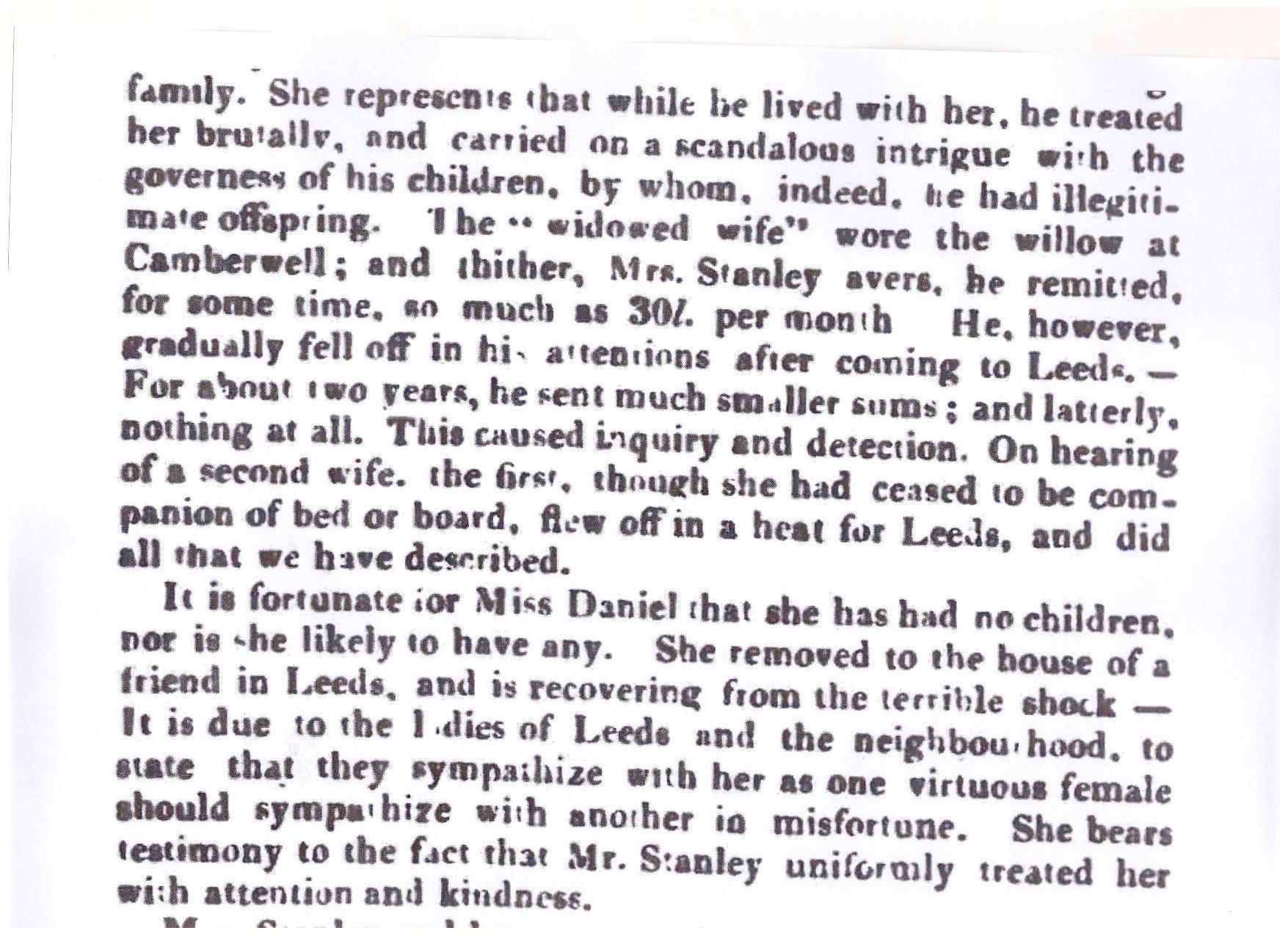

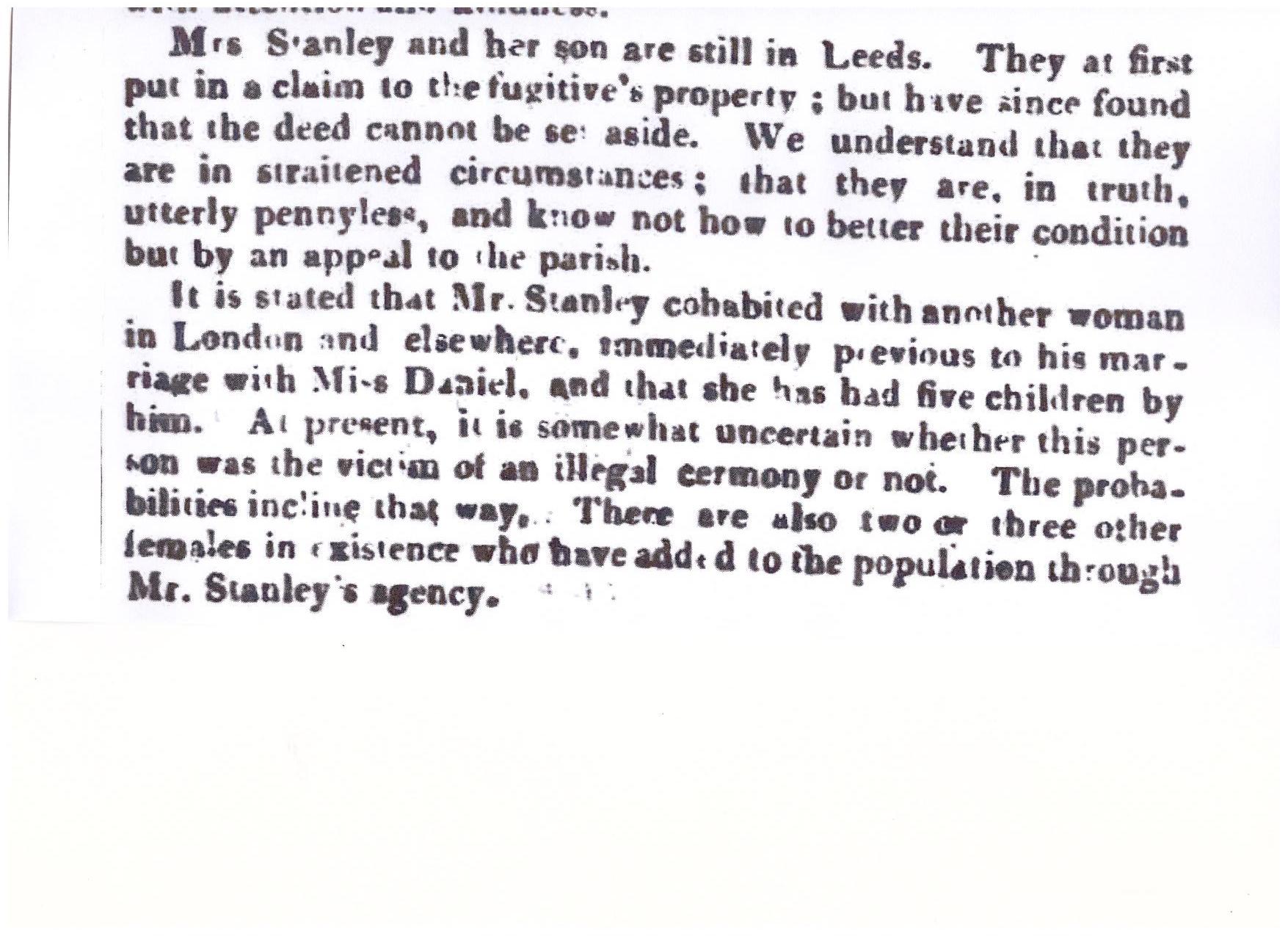

Reader, you will spot several differences between the above and the newspaper cutting below; but I’m going to stick my neck out and claim that this tale of John Stanley is the story that Bronte heard at Miss Wooler’s. I scoured the Assize Court records for the Leeds area in the 1820s and 30s; national and local newspapers; the National Archives, and I contacted the brilliant West Yorkshire Archive Service (thank you, Vicky Grindrod), and nothing else came close to matching the account in the cutting.

In his 1944 biography of Gogol, Vladimir Nabokov attacked the urge, among literary scholars, to seek out the “facts” behind fiction:

“It is strange, the morbid inclination we have to derive satisfaction from the fact (generally false, and always irrelevant) that a work of art is traceable to a ‘true story’. Is it because we begin to respect ourselves more when we learn that the writer, just like ourselves, was not clever enough to make up a story himself? Or is something added to the poor strength of our imagination when we know that a tangible fact is at the base of the ‘fiction’ we mysteriously despise? Or, taken all in all, have we here that adoration of the truth which makes little children ask the storyteller ‘Did it really ‘”?…”

Love it.

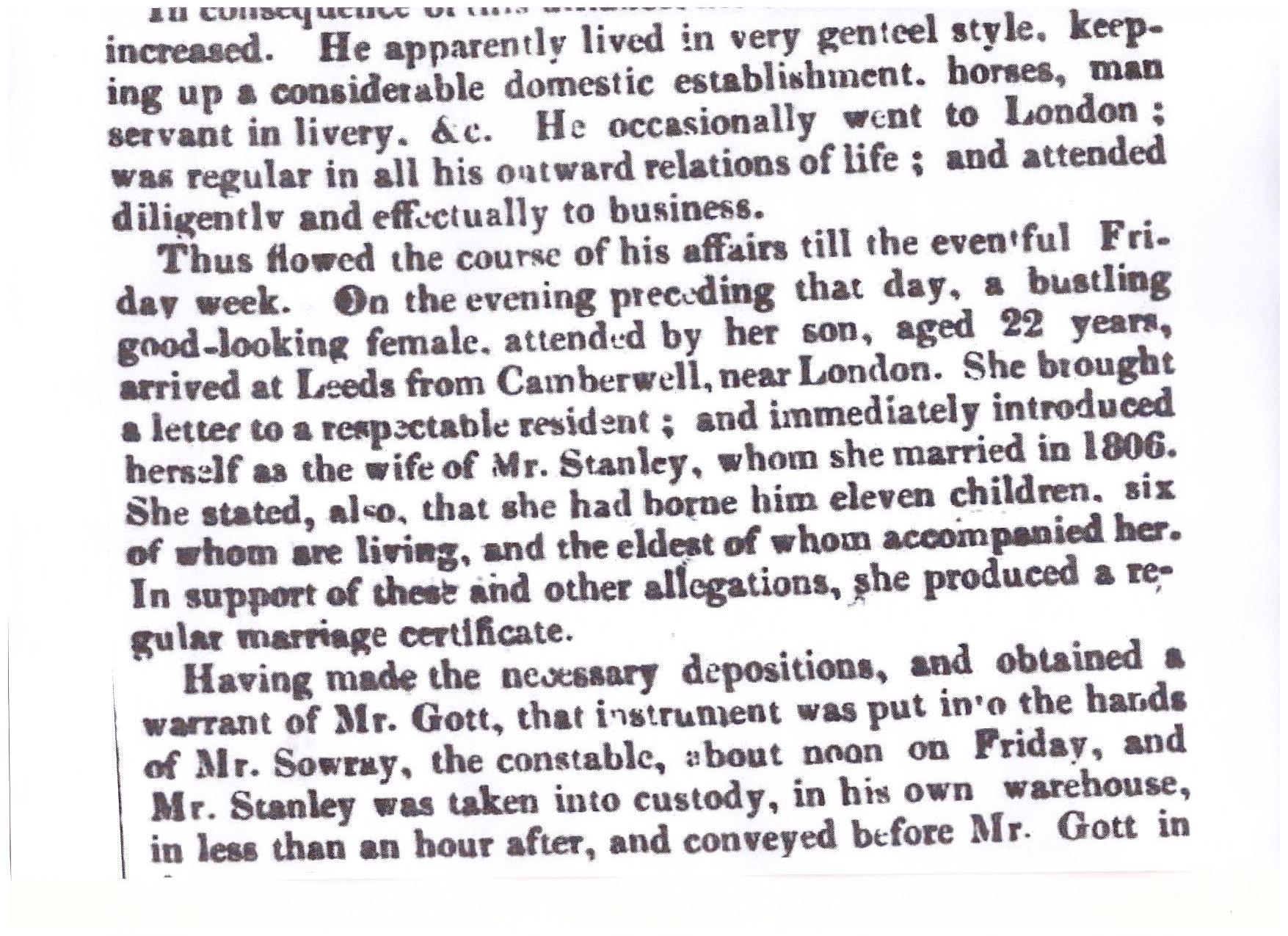

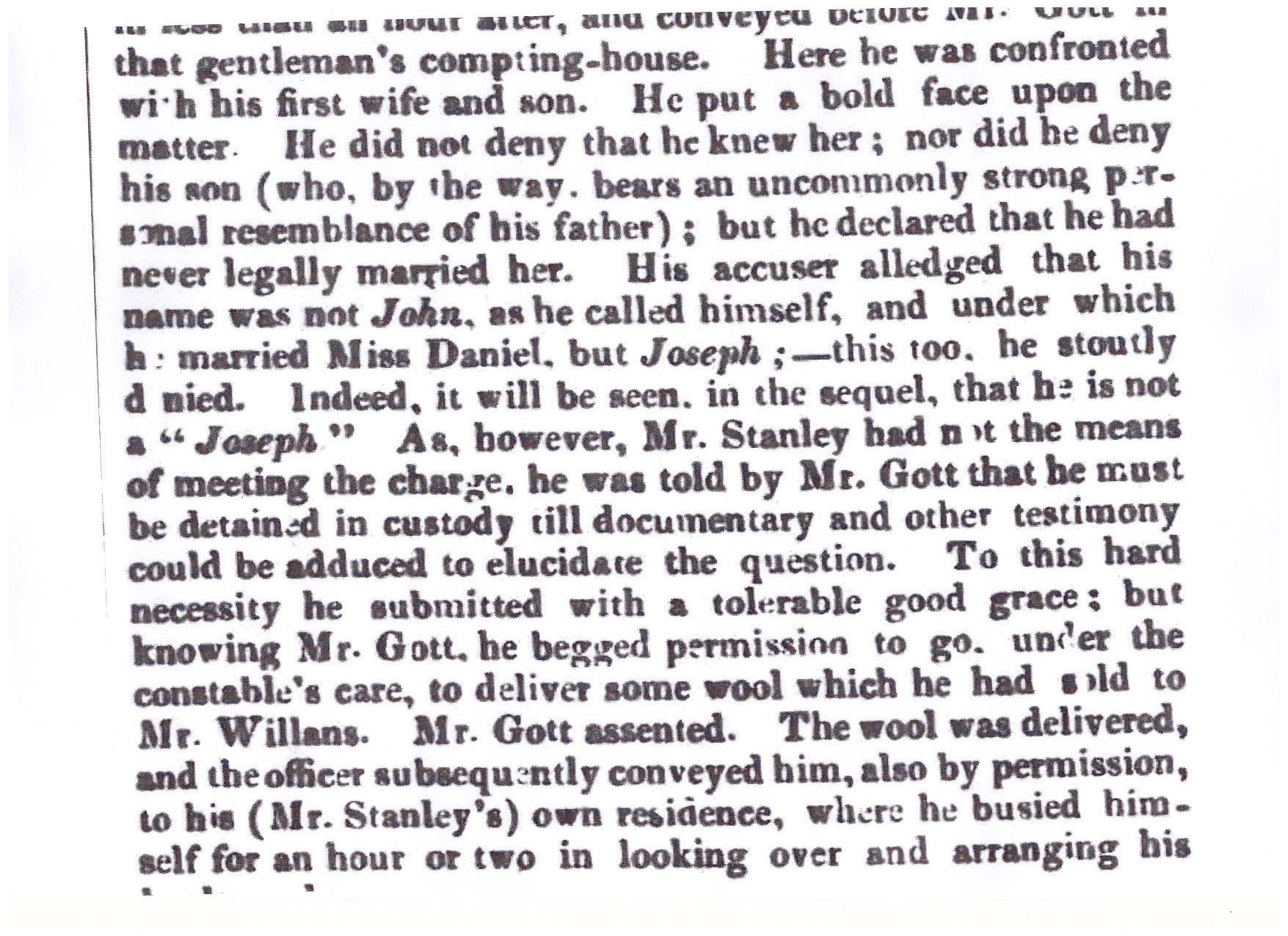

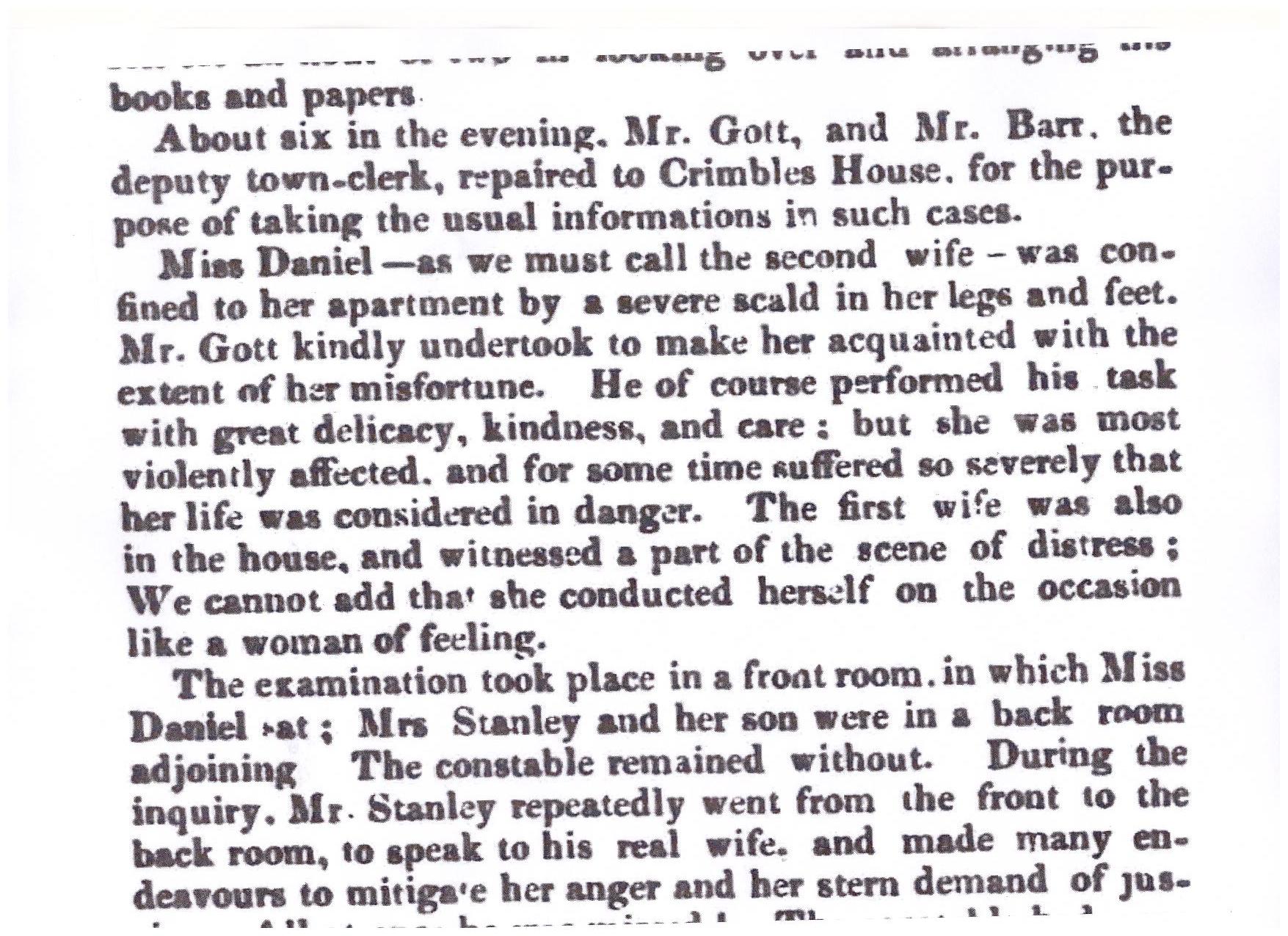

Now fast-forward 52 years, and here is Bronte scholar Juliet Barker, equally grieved that for certain folks, the Bronte sisters’ writings are often discussed in terms of “real-life” characters and incidents which are somehow deemed to “explain” their work. In a letter to the Sunday Times, published on 1 December 1996, Barker wrote: “The idea that there has to be a real original behind every person in the Bronte novels is an insult to their creativity.” So I’m posting the cutting not because it reveals anything at all about Jane Eyre, but because it was a fun bit of detective work to do, and I think it’s an interesting story in itself (and sort of gruesomely amusing, too). Mr Stanley is not Mr Rochester; Miss Daniel is not Jane Eyre; but see what you think of the Extraordiary Case of Bigamy At Leeds in The York Herald of 16 October 1830.