This fantastic original broadsheet was a very welcome present from a reader. Barry Trowbridge, from Kent (who, like me, worked as a newspaper sub-editor), wrote to me asking if I would like to relieve him of this item, which had lain around his family home for years. “For as long as I can remember, my family has owned this poster, or broadsheet, relating to the murder featured in your book. It forms the backing to a photograph of my grandfather and has been gathering dust under a wardrobe. I would like to pass it on to you, as someone with an interest,” Barry wrote to me. “It was printed by J. Catnach of 2 Monmouth Court, 7 Dials. [Catnach was a hugely successful purveyor of this type of cheap, one-off, catchpenny print.] It is similar to the broadsheets on pp241-3 of your book.

“There was always family talk about ‘the Italian Boy’ case. As for its history in relation to us, I’m afraid I don’t know any more than that.’

Barry was adopted, and his adoptive grandfather had died before Barry was born: the photograph (below) shows a rather severe-looking man with dramatic features. It is tempting to speculate that his grandfather’s own antecedents either knew the killers, or that he was descended from Italian immigrants; but there is nothing to go on in attempting to forge a link between the man photographed on one side of the piece of board and the broadsheet pasted on to the reverse.

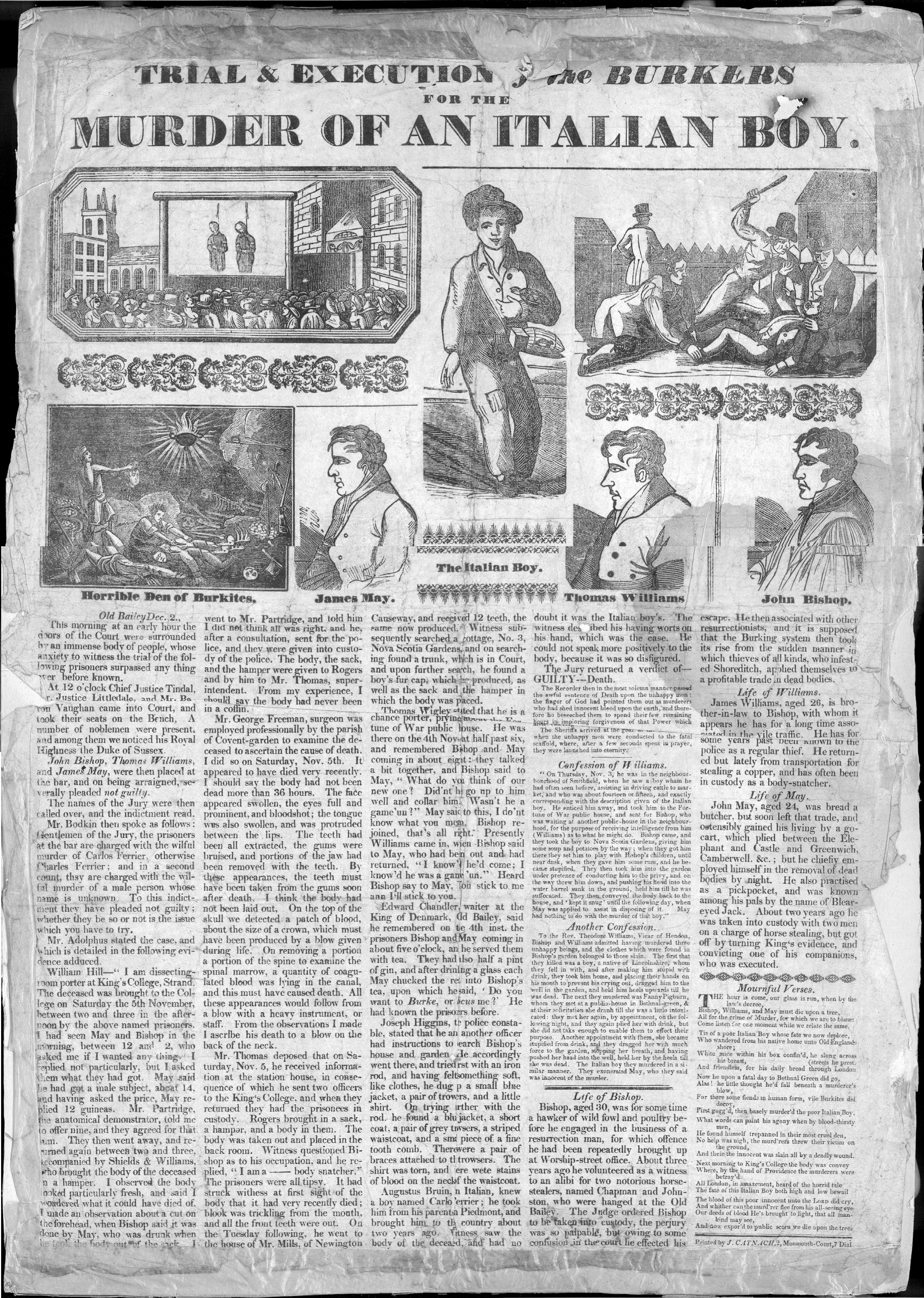

Like so much in the Italian Boy case (and in the history of broadsheets, for that matter), this item is packed with curiosities. Catchpenny prints often re-used stock imagery cut on to wooden blocks and so the pictures often bear little relation to the crime that is being reported on. With the Bishop and Williams case, for instance, many broadsheets simply re-used their Burke and Hare woodcuts of three years earlier, showing suffocation as the modus operandi. Above, James May and Thomas Williams as depicted by Catnach are simply the woodcuts of other previously reported criminals; but the John Bishop image is very similar to a sketch of him that had appeared in the Sunday Times report of the muder trial at the Old Bailey. Did Catnach shell out a little money to capture Bishop in a freshly cut new block?

The murder as depicted (top right) looks to me as though is has been taken from accounts of the 1824 murder of William Weare by John Thurtell and associates. (Just a guess – there are other 1820s crimes of which this could have been a representation.) The victim here is hardly a boy, and what on earth is that weapon? (Spoiler alert) No weapon was used on the Italian Boy.

Similarly, the “Horrible Den of Burkites” image has been imported direct from some other genre altogether. The house where the murder took place had no cellar at all, and no pile of skeletons (the point of murder-for-anatomy is to sell a fresh corpse for money, not to keep it stashed away until it became bones). John Bishop’s house had no holy grail appearing in mid-air, no decapitated heads being brandished.

I know, I sound as though I’m not grateful – that I’m sneering. But I really am thrilled with my possession, Barry. Thanks ever so.

For further reading on the world of the early 19th-century broadsheet: Thomas Gretton, Murders and Moralities: English Catchpenny Prints, 1800-1860 (1980); and The Story of Street Literature by Robert Collison (1973); and The Victorian Penny Blood and the 1832 Anatomy Act by Anna Gasperini.

The most significant collection of 19th-century broadsheets and other print ephemera is to be found at the St Bride’s Printing Library, off Fleet Street, http://stbride.org/library/contact